|

Looking back over the first decade of my life might cause a reader to believe I was of all people most miserable. Was I really that weighed down by judging eyes? Did I constantly feel guilty about something? Well, yes and no. My neighborhood in Canarsie was about 45% Jewish, 45% Catholic (mostly Italian, but also some Irish and Puerto Rican), and the rest Protestant: mainline, fundamentalist, and Pentecostal varieties. That equals a lot of guilt, but I doubt I felt more guilt than my Catholic neighbors. I know for sure I felt less guilt than Ralphie across the street. He was Italian. One year, probably during Lent, which we fundamentalist Protestants avoided religiously, Ralphie got hold of a couple of two-by-fours and some plywood. Using his dad’s hammer and some nails, he fashioned a cross just about his size. The workmanship was not bad for a kid of eight or nine. Ralphie took his cross door to door asking those who answered if they would nail him to it. He carried the hammer as well, and even some nails. Ralphie thought of everything. I’m not sure whose mom talked him out of it. It could have been Mrs. Sullivan, whose Catholicism was devout but didn’t extend to severe masochism. It could’ve been mine, who believed Catholics were going to hell anyway. I know neither I nor any other members of the 93rd Street Gang tried to talk him out of it. We just wanted to watch what happened. We Protestants weren’t supposed to feel guilty—something about Martin Luther and justification by faith—but we did anyway because we were constantly reminded we were “only sinners saved by grace,” emphasis on the “only.” I never questioned how we could be justified and guilty at the same time. Of course, I never questioned how Clark Kent could be Superman at the same time either. Theology is best left to someone other than preteens. I never understood why the Jewish kids in the neighborhood felt guilty. Their religion seemed so much more laid back than mine. Good religious Jews went to temple, or they didn’t. Drinking and smoking were personal choices, not evidence of deep personal failure or worse: backsliding. Still, my Jewish friends talked about feeling guilty a lot. Could it have been the level of blame we Christians placed upon them for killing Jesus, as if an oppressed people could have exerted such political pressure on their oppressors? Were they ashamed of having extra holidays or missing out on the joy of ham? I wonder whether some held survivor’s guilt inherited from every grandfather or great-aunt who escaped Eastern Europe in the 1930s and shared basement apartments with memories of those who were left behind. I never asked. Jewish holidays brought all the kids together in Canarsie’s public schools. Sure we had Christmas off, but that was like winter break. Easter week was like spring break. But Jewish holidays were real holidays. Jewish kids got off school, and, since half the class was out, the rest of us basically got the day off. And then came Hanukkah. Practicality dictated that New York City Schools couldn’t shut down for a week at Christmas and a week before that for Hanukkah, so everyone went to school and partied. P.S.114, where I attended first through sixth grade, had the best Hanukkah parties. We ate lots of candy, listened to the Jewish kids talk about getting eight days of presents, and we played with dreidels. Kids in Jewish nursery rhymes claim to make these little square tops out of clay. At P.S.114 they were made of plastic. By means of the Hebrew letters on the four sides, two things occurred: you learned some of the Hebrew alphabet and you could gamble for candy. P.S.114 in 2019 The Yiddish word for the candy we gambled for at Hanukkah parties is “gelt.” I think it comes from the gold candy coins given out for the holiday. Gelt brought out the gambler I never knew was in me. Every Hanukkah I’d wait for the dreidels to come out in our classrooms. Spin and take seemed to be my middle name, making my Jewish friends jealous. By the time those eight sacred days (and eight crazy nights) were over, I had a candy stash that would make the annual box of Louis Sherry Christmas Sunday school chocolates from Grace Church seem paltry and sad. I don’t know if I ever earned the title “mensch” from my schoolmates, but I was sure one lucky goy. Years later, I parlayed my dreidel experience into Saturday night poker games at Jonathan’s house. I don’t remember who played there regularly, I only know I was the sole Gentile and that none of us ever had a date on Saturday nights, or Fridays either. Poker was our social contract. I was generally as lucky at poker as I’d been at dreidel. Most times I’d walk home from Canarsie’s west-of-Remsen side in the wee hours of Sunday morning, my pockets bulging with pennies, nickels, and a dime or two. Along the way I’d stop at a stranger’s doorstep and tuck my winnings under the mat. I couldn’t keep it. I’d feel guilty. Next episode: take a trip with me to the wonderful place known as "Animaland." To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Isaac was—literally—the man upstairs. He was a distant relative of Mom’s who lived in the upper story of our formerly-one-family farmhouse. Yes, I grew up in a farmhouse in Brooklyn. We had a barn where Isaac parked his car, a chicken coop without chickens, a woodpile but no fireplace, and two grape arbors. One summer Pop even plowed up the backyard and planted row after row of sweet corn. It tasted good with lots of butter and salt.

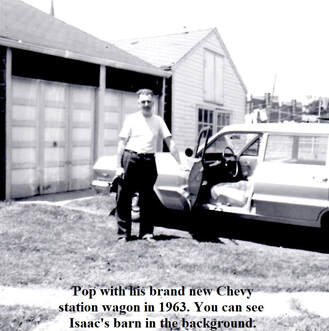

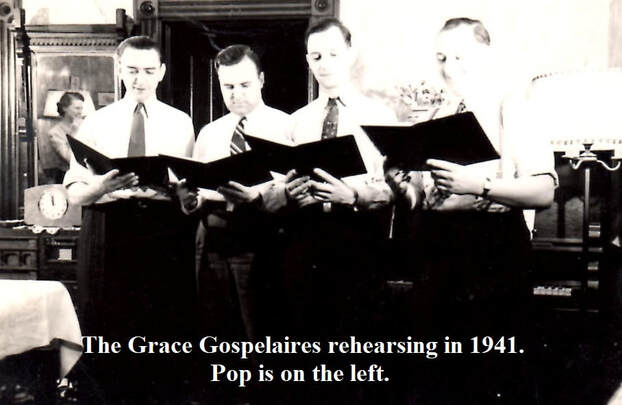

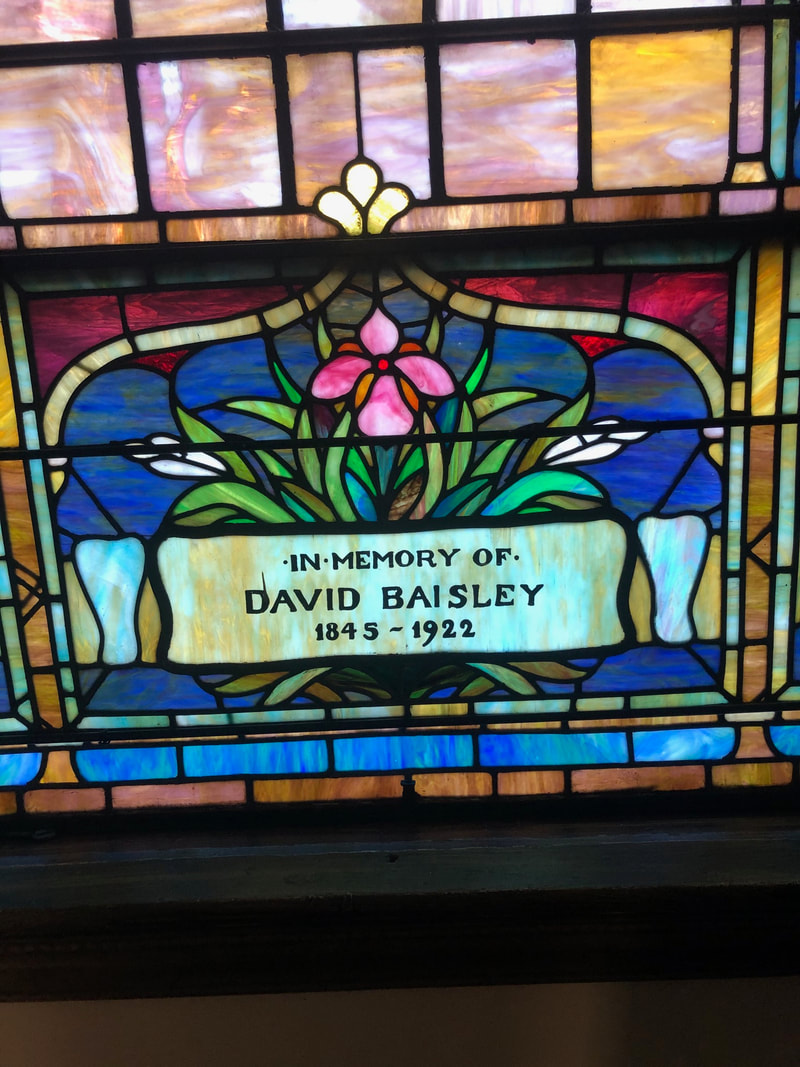

Isaac ruled his side of the yard with a rod of iron. With the exception of Mom and Pop being allowed to drive through his gate, across his concrete “apron,” and into our garage—next to his barn—we, mostly meaning my brother and I, were not to set foot in Isaac’s half-yard. Isaac wasn’t too crazy about kids playing in our side of the yard either. He’d complain to Mom about our ball games in the backyard (when there wasn’t corn) and our war games against the evil alien bush that possessed our front yard. We were too noisy. I ask you, how can one not be noisy when trying to rescue your best friend from the grasp of a crazed shrub from Planet X? And then there was the street. Streets in Canarsie were our playgrounds. You could get mugged in a park, but the streets were safe for playing touch football, punchball, and roller hockey. Isaac, however, laid claim to the part of East 93rd Street that ran past our house. I couldn’t count the times Isaac would open his bedroom window, stick half his body through it, and swear at us for playing too loudly. We loved it. When you’re twelve there’s nothing more satisfying than getting a guy in his seventies all riled up. While we neighborhood kids might have given Isaac valid reasons for hating us, his animosity toward my parents went deeper. I recently learned why, and at the same time learned just how poor my family was during my childhood. Mom’s mom was a housekeeper. She worked for a Mrs. Matthews who owned the property at 1304 East 93rd Street. When World War II came along, my recently married mom and dad moved to Albany and took my grandmother with them. As often as possible they would return to Brooklyn with my toddling brother to check on Mrs. Matthews. While in Albany, Grandma died. After the war, Pop’s job in Albany ended and they wanted to move back downstate. For a while Mom, Pop, and John lived in an apartment so small you could touch both walls at the same time. By1952, when Mom was pregnant with me, larger quarters were needed. The downstairs at 1304 was vacant, and out of respect for Grandma, Mrs. Matthews let the Baisleys live there at greatly reduced rent. The owner, her brother Charlie, and her nephew Isaac, remained in the five rooms upstairs. Over time, Charlie got sick, and Mom served as his primary caregiver until he died. She did the same for Mrs. Matthews, preparing meals and generally looking after her and Isaac. Eventually, Mrs. Matthews died as well. Isaac, for whom Mom had also cooked and cleaned, looked forward to inheriting the entire house and raising the rent, effectively forcing Mom and Pop out. Mrs. Matthews had other plans. Mom and Grandma, who had served her so long and so well, received their unexpected reward. Mrs. Matthews left the property to Mom, but there was one stipulation: the Isaac clause. So, if I ever needed to know the wrath of the man upstairs, all I needed to do was shout or hit a ball or trespass onto his side of the yard. In the Bible, one of the words for sin has to do with overstepping a boundary: forgive us our trespasses. To trespass against Isaac brought immediate judgment from the man upstairs. While I lived in constant fear of Isaac’s wrath, at least he was someone a kid could get away from. More difficult was living in the shadow of the man downstairs—my dad. Don’t get me wrong, John Arthur Baisley II might have been the best father who ever lived, but he was also a very public churchman. Pop served on Grace Church’s “Official Board.” Yes, that’s really what they called it. They weren’t elders or deacons, Ministry and Oversight, or Session. They were a board and they governed officially: the Official Board. Sometimes Pop chaired the board, and sometimes he served as vice-chair or secretary. I can’t recall him ever not sitting on the board although I remember him on many nights coming home late from a meeting wishing he had never seen the inside of a church. Along with his board membership, Pop taught one of the adult Sunday school classes and sang in the choir. He also sang first tenor in a gospel quartet, the Grace Gospelaires, a ministry he truly enjoyed for 30 years. Hitting those high notes in The Happy Jubilee made him somewhat of a legend among local believers. The Gospelaires sang at churches throughout the greater New York area. Once a month they led the Monday night service at the Bowery Mission in Manhattan. I remember how excited I was, as a boy of maybe thirteen, when Pop invited me to ride along to the Bowery with the quartet. This was the big time. This wasn’t just singing background for a chalk artist on the Island (meaning Long Island, pronounced lawng-GUY-lind), this was the City! That night I sat in the front row as the Gospelaires performed their set. I was so proud when Pop sang his solo, Frederick Lehman’s The Love of God. I turned in my seat to look at the group of men who’d wandered in off the street for a warm seat and a hot meal. A few slept soundly. A couple more joked between themselves. No one seemed to care that my dad was pouring out his heart on their behalf. On the ride home I asked Pop if he ever got upset about that. “They’re not the only ones we’re singing for,” he replied. Pop was a public Christian. He seldom received pay for his ministry, but he was well known for his music and comedy, often accepting requests to emcee local wedding receptions. I grew up as the “little Baisley boy.” Believe me, when the little Baisley boy went to the altar at Rally Day, everybody knew it. My life changed almost overnight. I recall feeling more accountable for my behavior, like I wasn’t being cut the amount of slack I’d known before. I felt a hundred pair of eyes watching me every minute. You’ve got to remember that to the best of my knowledge my only sins were disobeying my parents and briefly stealing one bubble gum. Suddenly I was a “born again” Christian and the bar reached new heights. Maybe it was just a feeling. Maybe not. A few years later I was a preteen trying to live up to my calling. A younger boy whose family occasionally attended our church was running rampant through the sanctuary after a Sunday service, during a fellowship dinner or some such event. I tried to get him to stop, but he ran past me, knocked something over, and yelled for his mommy. Mommy ran in, looked over the situation, glared at me and pulled her boy away. “Stay away from him,” she warned her little angel of me, “He doesn’t know the Lord.” And there I was, back at square one. Being the little Baisley boy couldn’t save me. Praying a prayer with an evangelist at Rally Day might have had some effect on my eternal destiny, but I lived in Canarsie. The streets had recently been repaved but not with gold. If I really didn’t know the Lord, and at least one adult in Grace Church believed I didn’t, then who was I? Not long after, the Animals recorded their cover of the Nina Simone song, Please Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood. From the moment I first heard it on WABC radio, probably spun by Cousin Brucie Morrow, I had my life’s theme song. Next episode: how growing up surrounded by Jewish and Catholic neighbors heightened my sense of guilt but taught me to appreciate "gelt." To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. For all have sinned and come short of the glory of God. For the wages of sin is death. It is appointed unto men once to die; and after that, the judgment. Pastor Watt’s words landed heavily on my ears, but that’s not what scared me. It was his eyes. As he preached words straight from the King James Bible, his eyes dug a channel to my soul. I was a sinner. I was condemned. I was born in sin and destined for hell if I didn’t repent. Of course, I had no clue what repentance was. I was five years old. I was born just past midnight on a Thursday in 1952. I didn’t go to church that Sunday or the next. On the third Sunday, when Mom was fully recovered from giving birth to her second son, I went to church.

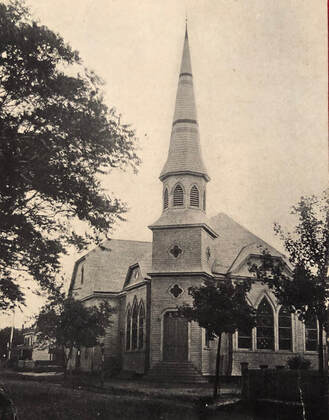

Back then the church had a longer name: Grace Methodist Protestant Church. It was part of a small denomination (Methodist Protestant) that in 1939 was absorbed into the Methodist Church (now the United Methodist Church). Some Methodist Protestant leaders walked out of the convention that produced the merger. They felt that Methodism was becoming too liberal in its theology. Clifford Kidd did not walk out. Kidd reasoned that, since the Methodist denomination owned the church buildings, any church that tried to break away would be left without a place to gather. He in fact believed the Methodist Church was becoming liberal, but he did not want Grace to lose its building. Once he had secured from the Methodist Church the right to retain their building, Kidd led Grace out of Methodism once and for all. From then on, Grace had the generic-sounding name, Grace Protestant Church; Grace for short. Grace’s pastors were drawn from the ranks of independent Baptists, as independent Methodist churches like Grace were few and far between. This led to minor internal controversies like what to do about baptism and how and when to celebrate Communion. My introduction to Quaker beliefs probably came when Pop told me one day, “The only baptism that really counts is being baptized by the Spirit,” a very Quakerly concept. “Pop” was John Arthur Baisley, Jr., my dad. I’m not sure whether my brother, John, had been calling him by that name during the ten years before I was born, or whether “Pop” was a shortened version of “Poppo,” the father’s nickname on The Patty Duke Show, which was a favorite of mine as a preteen. Either way, we called him Pop, and Caroline Frances Armstrong Baisley was “Mom.”

I can’t recall ever feeling the love from above when we sang that song. It was the Father looking down that captivated and terrified me. Years later, as a high school junior protesting the Vietnam War, I hung a print of James Montgomery Flagg’s famous “Uncle Sam Wants You” recruiting poster on my bedroom wall. No matter where you stood or sat in my room, Uncle’s finger was aimed at you. I figured Father’s gaze was the same. The thing is, I believed I deserved it. My only transgressions were occasionally disobeying my parents (a practical interpretation of the fifth commandment written, no doubt, by the parent of a middle schooler) and stealing a one-penny Bazooka bubble gum from the corner store, which I returned almost immediately. But like the apostle Paul, I believed I was the “chief of sinners.” Being an accomplished sinner at age five, I was more than ready to be born again, saved, washed in the blood, and every other redemptive verb in the Christian fundamentalist dictionary, and my church was more than willing to accommodate me. Being unwilling to waste even one chance to bring a worm such as I to the throne of grace, we regularly had altar calls in the aforementioned Opening Exercises. I held out for a while, clinging to my sinfulness. Then my church pulled out their secret weapon: Rally Day, Sunday school on crack with a children’s evangelist dealing. I’ll paraphrase a story my mother told me about my first experience of salvation. I was almost five when Rally Day featured a chalk artist. Chalk art was very popular in evangelical churches of that era. My dad even spent some time as a songleader/soloist for one of these artists. To this day they fascinate me with their art; drawing one picture and then revealing a second under black light. Five-year-old me watched the gospel story unfold under black light. When three crosses mysteriously appeared on the hill, I saw my terrible self, nailed there with Jesus. When the artist called for anyone who wanted to ask Jesus into their heart to come to the altar for prayer, I couldn’t wait any longer. I prayed the sinner’s prayer and my life gloriously passed from darkness to light. So my mother said, and she summarized it on a page in a little blue-bound New Testament the church gave me to commemorate the big day. I remember nothing of it. It must have been exciting for my family and my church, though. If walking the proverbial sawdust trail (it was scarlet carpet as I recall) saved me from the judgment of God, it also put me squarely in the center of judgment from everyone else in church. That’s what happens when you become a public Christian. I went through my early years ever aware of God’s judging eyes looking down on me. Being saved, this might have been a source of comfort to me. I can’t say it was; it was more like, “Jesus loves me, this I suspect, but still I’d better eat my vegetables.” It was hard for me not to be in the public eye. My mom taught Sunday school, sang alto in the choir, and was active in the WCTU, a temperance organization that featured “white ribbon babies.” I was one of those little ones whose wrist was circled with a white ribbon as a sign of Mom and Pop’s pledge that liquor would never touch my lips as long as I lived in their care. It almost worked, too. My only taste of alcohol until my early twenties was a tiny sip of rye from a bottle found in the pantry of the man who lived upstairs. Some people call God “the man upstairs.” That reveals more about their theology than about God. First, it places the Creator squarely in the camp of one small part of creation, the male of the human species. Second, it emphasizes one of the least attractive qualities of that being, the annoying tendency to want to dominate others, especially the female of the species. I never needed a god like that; I had Isaac. More about "the man upstairs" next episode. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I am a product of the 1950s. I came of age in the 1960s, went to college in the 1970s, and never moved back. I like to tell people that Brooklyn is a great place to be from; and it is. You can’t grow up in Brooklyn, or any of the Five Boroughs, without acquiring a raft of stories. Every New York City kid can recite a list of famous people they went to school with; even though, in most cases, classes were so huge you hardly knew any of them. Every New York City kid has a tale involving pizza or do-wop or stickball or subways or knowing someone whose second cousin once almost saw a Mob hit. You’ll read my tales in the pages to come. I am also a product of American fundamentalism. These days the word fundamentalism is synonymous with ignorance, hatred, and absolute closed-mindedness. Another synonym is evangelicalism. Let me say at the outset that things were not always so. There was a time when fundamentalists were known for their academic prowess, although their theology was conservative. Evangelicals, those we now think of as backward, backwoods neo-Nazis, were derided by fundamentalists for being too liberal. And Billy Graham, that poster boy for American conservatism, was considered to be far left of the Christian center.

While the ninety essays by biblical scholars of various Protestant denominations spoke to many nuances of scripture interpretation, they soon were digested down to five foundational beliefs. The scholars and their California benefactors understood these to be the truths on which the Christian religion was established. Although the wording may appear different, based upon whose recollection one reads, I will list them as I remember them from Theology 101 in Bible college. They are 1) the verbal inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible; meaning, the Bible is literally true except where it is obviously metaphorical, such as Jesus’ parables, 2) the virgin birth of Jesus Christ, 3) the substitutionary atonement of Christ (hooboy, I didn’t realize how theologically weird this might sound to the average reader); that is, Jesus died on the cross to pay the penalty for our sins, 4) Jesus’ physical resurrection from the dead; in other words, he didn’t fake it, he arose, and 5) Christ’s bodily return, which means he'll be back someday à la Arnold Schwarzenegger. Those are five theological statements. They were proposed and believed by men with degrees from schools like Yale and Princeton. They can be used to judge other people’s theology, but they say nothing about the things presently associated with fundamentalism; such as reproductive rights, discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community, trickle-down economics, and the Second Amendment. Mom and Pop were devout fundamentalists until the day they died. They never smoked or drank alcohol; they told me drinking or smoking was my choice to make. They prayed for my Jewish friends to believe in Jesus as their Messiah, but they never gave those friends an ultimatum; nor did they ever cease to welcome anyone of any religion, race, culture or expression of sexuality into their home. To Mom and Pop, to do such a thing would have meant denial of the very fundamentals on which their faith rested. They had a lot to say regarding my state of spirituality, however. They wanted me to be “saved” at an early age. To be saved meant that I made a conscious choice to “accept Jesus Christ as my personal Saviour.” (Yes, we used the King James Version spelling in our house.) You will read in the next chapter just what that choice meant to a kid like me. They wanted me to live a “Christ-like” life, but they left the how-to of that life up to me. They were good parents; a little too Leave It to Beaver maybe, but good. You still find Mom and Pop’s brand of fundamentalism today in the quiet corners of American religion. It’s the kind that says, “I don’t understand why you two gals want to marry each other instead of some nice boys, but I’ll bake you the best darn wedding cake you ever dreamed of.” Mom hardly ever baked, but if she had, yeah, she’d have said that. Welcome to my world. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I’m sure a dictionary definition somewhere explains that memoirs are supposed to be factual, and this one is. But it tells stories I lived going back sixty years, and while they’re all true, they may not have actually happened as I remember them. I, like every other memoirist except the ones who live in dictionaries, have a very selective memory. There are a lot of really funny and poignant stories you won’t read here simply because I’ve forgotten them. The stories you will read here are flavored by my memory, which means they may be slightly distorted by age, sentimentality, and maybe even the desire not to be quite as candid as I intended. I don’t mean to mislead anyone. These pages will reflect the first two decades of my life according to my best recollection of them. Perhaps the best example of the way ancient stories don’t get retold exactly the way they happened comes from a social media conversation between myself and Todd Nahins, one of my best friends in junior high school and dearest friends ever. It happened after he read the first couple of chapters you will soon read yourself. Todd remarked, “You may not remember, but when you and I were in high school we had a discussion on my being saved. It went something like this: Phil: We need to talk. Todd: About what? Phil: What I have to tell you is something you need to accept once I tell you. Todd: Maybe don’t tell me. Phil: I have to. Todd: Why? Phil: If I tell you and you don’t accept it, you will burn in hell. Todd: That makes no sense. Phil: Those are the rules. Todd: What if I live a good life, give to charities, and never do anything wrong? Phil: I can get you purgatory. Todd: Can we talk about something else? Phil: I’m dating your former girlfriend, Linda. Todd: Now who’s in hell?” I said, “Todd, that’s not the way I remember it.” To which Todd replied, “Sounds pretty close to me.” And maybe it is. You might wonder where my connections are to earth-shattering events such as the day JFK was shot, the Miracle Mets, Super Bowl III, and the moon landing. I wondered that myself as I read and reread the manuscript. I finally reached this conclusion: as big as these events were—and believe me, the 1969 World Series was so big we were given class time in front of TVs we only thought could be tuned to the education station—they did not affect kids the way sledding down a snowy hill or working up the courage to ask a girl out on a date did. I remember the tears in Mrs. Wilson’s eyes when she told her sixth grade class that the president had been shot, but I was touched in a deeper way when she gave the class mementos of her recently deceased husband. I watched the moon landing, but I was more in awe of knowing that a girl I admired was watching it at the same time on the other end of a telephone line. So this is my story. It’s true, although not always accurate. It’s complete, but it has a lot of gaps. It’s mine, but I hope you may see a bit of yourself in it as well. A Word about Names I endeavor to be as accurate as possible in writing about friends, family, and neighbors gone by. For that reason, I contacted as many folks as possible from my past. Almost all I could locate graciously gave me permission to use their real names, and for that I am grateful. Those I could not locate, and most of those who have passed on, were given different names. Immediate as well as extended family names have been unchanged, as well as most of the locales described. Within the text I will make no mention of which names have been changed and which have not. Episode Two Preview Episode Two will delve into the religious milieu in which I was raised: mid-century Protestant fundamentalism. Sounds stifling, judgmental, and boring, doesn’t it? Well. It was and it wasn’t. Tune in next week and find out. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed