|

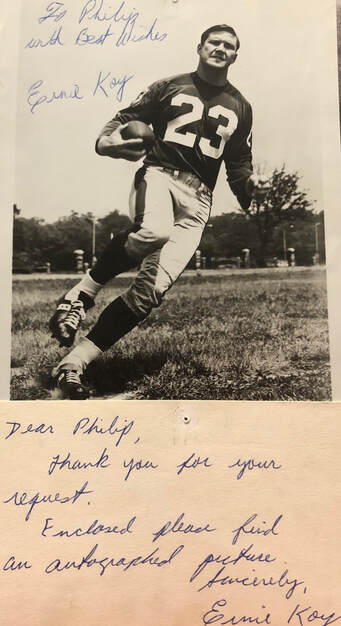

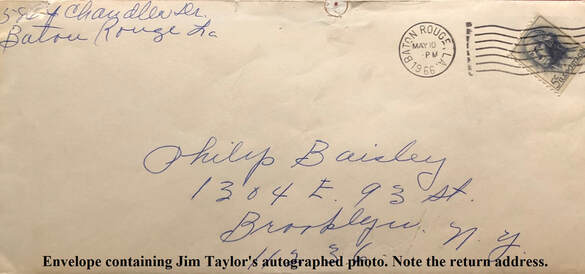

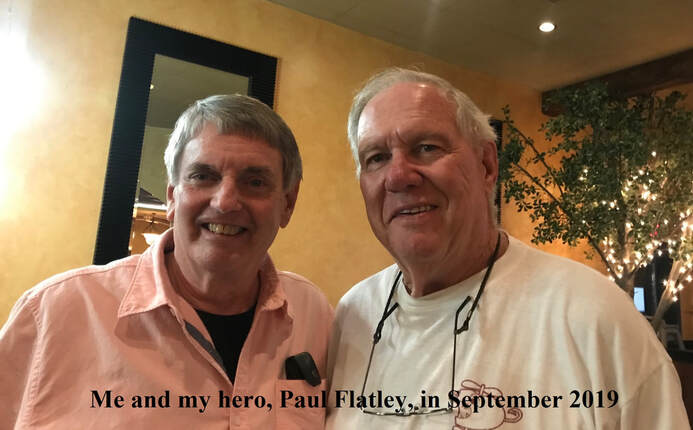

The last episode ended with a story of how I, in an act of pure elation, broke my big toe watching the New York Mets win a baseball game in 1966. That was just the first of my toe mishaps. My second broken toe was a true athletic injury, but much less interesting than my first and third. During soccer practice one fall day at Lancaster Bible College I attempted to kick a ball at the exact moment a scrimmage opponent slide tackled the ball. My foot slammed into his hip, breaking the middle toe. Just your basic soccer injury. I rested the remainder of that day and returned to practice the next, my toes taped together. My third athletic injury, and third broken toe, may go down in the annals of sports as the world’s first somnambulant volleyball mishap. Sandy and I were living outside Greenfield, Indiana, at the time, where I pastored a Quaker meeting. (A Quaker meeting is almost exactly like a church, but don’t tell Quakers that.) One night I had an incredibly exciting dream wherein I was playing volleyball in a gym with hardwood floors. In an attempt to defend against an opponent’s spike, I dove for the ball. Although the gym was brightly lit, in the instant before I hit the floor I realized everything had gone dark. For one split second I grasped reality. Then I felt the impact as my body landed on the hardwood, but not in a gym. I had dove out of bed, landing hard. As usual, a toe got the worst of it. This was my middle toe again, but on the opposite foot from the old soccer injury. Hurt like hell though. Volleyball, the wide awake kind, was one of the things Grace Church’s Men’s Fellowship group did regularly. We didn’t have our own gym, but a church in Lynbrook did, and three or four church men’s groups played there. The games were fun and very competitive. But there was no swearing at muffed digs, blocked spikes, or bad calls. Christians, at least “real” fundamentalist Christians like us, never swore—ever. Men’s Fellowship also featured ping-pong and shuffleboard. Grace Church had two tables for the former and numbered tiles built into the fellowship hall floor for the latter. Pop was a pretty good ping-pong player, but Turner Kidd was the champ. Turner, Babe Kidd’s brother, was almost unbeatable. When, as a high school sophomore, I was old enough to join the Fellowship, Turner made my ping-pong education his priority. He could put topspin, sidespin, backspin, and sometimes combinations of two spins on the ball. At first, playing against Turner brought me embarrassment and the laughter of the older men. But I didn’t give up. Over the three years I was in Men’s Fellowship I learned so much about ping-pong. By the time I left for Bible college I could beat all the other men regularly and, occasionally, Turner himself. The most fun times at Men’s Fellowship weren’t the games during meetings. And they certainly weren’t Pastor Watt’s Bible studies, although he did make them interesting enough to appeal to my Jewish friends who tagged along on Friday nights for the ping-pong and coffee. The most fun thing we did was going to minor league hockey games a couple of times each winter. In the 1960s, Long Island didn’t have an NHL team. This was before the Islanders. Manhattan had the New York Rangers, and they were our heroes, but we couldn’t afford tickets to see them; and anyway, the subway was for baseball, not hockey. What Long Island did have was the Long Island Ducks, the living breathing incarnation of the old sports joke, “I went to a fight, and a hockey game broke out.” The Ducks played at Commack Arena, a pint-sized venue in Suffolk County. It was a free-wheeling arena where kids could wander unsupervised all the way around the ice rink, being careful not to get in the way of the Zamboni. The games were free-wheeling as well. The skill level was minor league, but the desire was all-star. I only remember one Long Island Duck. I don’t know if any ever made it to the NHL or even to higher minor leagues. But the teams they fielded during the 60s, led by the incomparable John Brophy, were a kid’s dream. According to Wikipedia, during Brophy’s playing career he amassed more penalty minutes than any other player in Eastern Hockey League history. He didn’t seem to be especially large—the enforcer type—he simply had a perpetual chip on his shoulder. If an opponent wronged him or a Duck teammate, Brophy skated in, grabbed the enemy’s shirt, and tried to yank it over his head while pummeling his body. We loved Brophy. Eventually, in a long minor and major league coaching career, our hero garnered over a thousand victories, second highest of any pro hockey coach. When I was very young, even before I appreciated Brophy’s fists, I think I still loved hockey. It was the Zamboni. The magical way it turned a rough skate-gouged surface into frozen glass was captivating. And when Billy Knudsen and I waited for it to clear the ice, standing in hushed silence in the tunnel behind one of the goals, we knew we were about to glimpse Behemoth, the monster described in the Book of Job. Everything seems bigger when you’re a little kid. Not Zambonis. They were, are, and always will be the giant machines that make indoor ice hockey possible. If baseball was our field of dreams and hockey our magical playground, then football was the spectator sport that was both unattainable and close. We played football in the street. We watched college football twice a year; on New Year's Day, when almost all the “big games” were played, and on the last Saturday of the regular season, when the Cadets of West Point played the Midshipmen of Annapolis in the Army-Navy Game. We always rooted for Navy because of John’s service as a Marine. Our passion, however—mine, my family’s, my neighborhood’s—was the National Football League, even though we never saw a game in person. The New York Giants were one of the earliest teams to enter the NFL, and they were our team. Pop would tell stories of the great Sam Huff, Frank Gifford, and Y.A. Tittle. I still have a little plastic football the great quarterback Tittle autographed for Pop when he appeared at a convention in Pop’s building on Eighth Avenue. As I was growing up, the Giants were “rebuilding,” which is a polite way of saying they stunk. Every once in a while, there’d be a glimmer of hope, like when Tucker Frederickson and Ernie Koy teamed up in the backfield, or when it appeared that Homer Jones might be the fastest wide receiver in the League. When they acquired Fran Tarkenton from the Vikings I thought they might finally have a great quarterback again. Well, the “Scrambler” was great, but the Giants overall were not. When the American Football League came along, we added the Jets to our favorite teams. They stunk too, for a while. Then “Broadway Joe” Namath hit town and lit a spark that resulted in the Jets beating Baltimore in Super Bowl III. Secretly, I loved the Minnesota Vikings. In our electric football games, I always called my team the Vikings. Scott even gave me a hand-painted set of electric football players in purple uniforms so I could actually “own” the Vikes. My not-so-secret love of the Vikings extended to fantasy. I often daydreamed about being a Viking flanker back. I’d wear number 25 and line up in the backfield between Fran Tarkenton (who was back with the Vikings after a short time with the Giants) and my hero, wide receiver Paul Flatley, #85. Flatley and I were the Vikings’ one-two offensive punch in my dreams. We could outrun or outmaneuver every defensive back in the League, giving Tarkenton two targets for the inevitable touchdown pass. While pro football filled our dreams and street football filled our afternoons, the NFL was unattainable due to ticket prices we couldn’t afford and the fact that they played on Sundays. One didn’t miss church, or leave the service early, to watch big guys crash into each other on a grass rectangle. It just wasn’t done. Even the argument that born-again Christians like Fran Tarkenton played on Sunday, didn’t sway my parents. So NFL games were out of reach, but not the players. One winter day in junior high, Scott came over with a treasure he’d just received in the mail. It was the official—you knew it was really official because it didn’t say it was official—public relations book for the National Football League, and it was called The NFL and You. It gave the previous year’s stats for every team, contained some great photos, and included the mailing address and phone number for every NFL team. “You know what we can do with this information?” Scott exclaimed. “We can write to the players. Maybe they’ll write back.” It sounds absurd now, in the days of autographs for a fee, that at one time pro football players were accessible, even wanted to interact personally with their fans; but back in the 60s, multi-million dollar contracts and layer after layer of lawyers, accountants, and other hangers-on did not separate sports idols from their fans. Having an NFL player for a pen pal didn’t seem far-fetched.

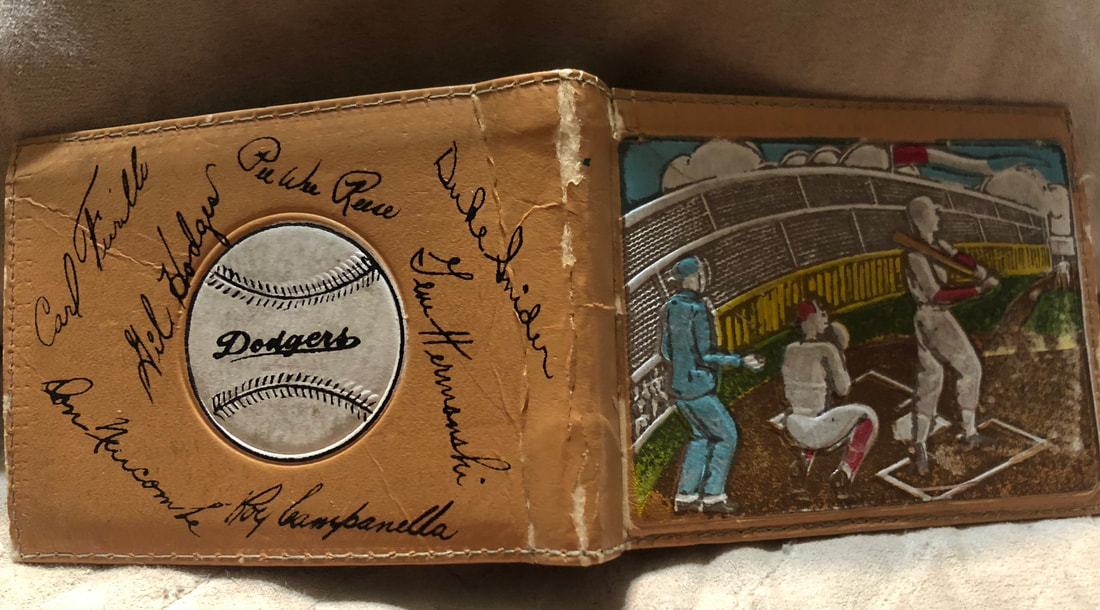

That’s pretty much the way it was for pro footballers in those days. You had your Jim Brown, who was utterly unapproachable, but other superstars like the Packers’ Paul Horning, Jim Taylor, and Bart Starr wrote back. And then there was Gale Sayers. Sayers’ rookie season with the Chicago Bears established his greatness even before he amassed Hall of Fame stats and became even more famous as a character in the 60s tearjerker Brian’s Song, a film about the illness and death of Sayers’ teammate, Brian Piccolo. I didn’t get a manila envelope from Sayers, just a white #10 envelope with a 3x5” B&W photo wrapped in a sheet of paper. On that paper, Sayers had written the most beautiful words of gratitude I’d ever seen. He was genuinely impressed that I’d take the time to hand write a letter to a rookie football player. He signed the letter and the little picture. I was so enamored with Sayers’ response, I wrote back to him. Unfortunately, figuring he’d forget what he’d written to me, I included his letter to me with my letter to him. I never heard from him again. I still have the original autographed picture, though; and it’s me, not him, I’ve never forgiven. I finally got to a pro football game in the early nineties: the Steelers versus the Chiefs at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. It was fun being there with my son, Stephen, and some editor friends. By then, however, the idea of meeting a player before a game, or getting a free, personally-signed photo, was a relic of bygone days. But sometimes miracles happen. A few years ago I was sitting on a stool in the bar of my favorite Richmond, Indiana restaurant. I go there mostly to read and enjoy a Jack on the rocks and a nice Italian dinner. I pretty much keep to myself, but on this particular night there was a hockey game on TV. You know how Baisleys can’t resist a hockey game. The white-haired gentleman beside me struck up a conversation, remarking that he didn’t grow up with hockey but had learned to love the sport. I told him about my lifelong love of the game. I probably told him one or two of these same stories. He said, “I got into hockey when I was coaching football at Northwestern. My wife and I went to a lot of the home games. I really enjoy it.” Then he angled toward me on his barstool. “Sorry. I never got your name.” “Phil Baisley.” I replied. He grasped my hand. “I’m Paul Flatley.” “Number 85!” And once again I was a kid standing in a stadium parking lot shaking hands with his hero. Some things, ya’ just don’t talk about when you’re a thirteen-year-old boy. You wait until you’re too old to care, as you’ll hear in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Inevitably, when people find out I’m from New York, someone will ask, “Are you a Yankees or a Mets fan?” I can honestly answer that I’ve been both. My earliest recollection of Major League Baseball is the 1960 season. Being undersized and often picked on, I became a Yankees fan because they personified winning, something with which I’d had little experience. I was an avid baseball card collector, and I knew the face and position of every Yankee. I can almost reconstruct a typical lineup without the aid of Google. I can’t remember who led off, so let’s try a process of elimination. Tony Kubek batted second and played shortstop. Mickey Mantle was in center, batting third. Roger Maris batted cleanup and played right field. The next year he would break Babe Ruth’s single season home run record, albeit with an eight game longer season. Moose Skowron played first and batted fifth. Yogi Berra and Elston Howard rotated behind the plate. They both may have batted sixth or seventh. Clete Boyer held down third base and probably batted seventh. Bobby Richardson, always stellar at second but never much of a hitter, batted eighth, before pitchers like Whitey Ford, Ralph Terry, and Luis Arroyo. That leaves Héctor López playing left field and batting first. That’s the way I remember the team. I may be wrong, but as true baseball fans always say, “You can look it up.” The 1960 season was a heartbreaker for the Yankees. They did fine during the regular season, clinching the American League Pennant early in September. It was the World Series that brought the pain. That was where Bill Mazeroski became the unlikely batting hero who won it for the Pirates with a walkoff home run in Game 7. I cried. The next year the Yankees had essentially the same team. This was before free agency, and players stuck around—or were held captive by owners—year after year. The Bronx Bombers won the Pennant handily and defeated the Reds in the series. They were my team. And then they weren’t. Kubek was gone in ‘62, replaced by a guy with the godawful name of Tom Tresh. I hated that name, and I missed my shortstop. Then Joe Pepitone started playing first. I could not imagine life without the Moose at first. The Yankees were losing my allegiance. The 1963 season was special for Pop. That year, although my former heroes, the Yankees, won the AL Pennant, they lost the series four straight to the Dodgers. Pop finally forgave the Dodgers—almost—for moving from Brooklyn when they beat the despised Yankees. I remember listening to one of the games on the radio in a Jahn’s ice cream parlor. Pop had loved the Dodgers all his life. They were his “Bums.” During their greatest seasons they would still manage to lose the NL Pennant to the Giants or the Series to the Yankees. But it didn’t matter in the long run. The Dodgers were the Dodgers. There was always next year. They were Pop’s team. They were never really my team. My team was created the year I gave up on the Yankees, 1962. They were the New York Mets, who lost more games their first year than any team ever in a single season. I fell in love with them. Who wouldn’t love a team with players’ nicknames like “Iron Hands” and “Doctor Strangeglove”? They were so bad they were wonderful. They were the “Amazin’ Mets” long before they won the 1969 World Series. Every child remembers their first trip to a Big League stadium. Mine was to see the 1963 Old Timers Game that was played before the June 23rd Mets game at the ancient Polo Grounds in Manhattan, where the team played their home games before Shea Stadium. Pop took me there to see his old heroes from the Brooklyn Dodgers. Old time Yankees and Giants played in that abbreviated game too. Later the Mets lost. I really didn’t care. I was in another world from the moment we went through the turnstiles. There’s a moment in the movie The Wizard of Oz when everything changes from black and white to the primary colors of Munchkinland and the greens of the Emerald City. The Polo Grounds was my Oz. Emerging from the entry tunnel was like seeing color for the first time. Never, no matter how Pop tried with his side of the yard, had I seen grass so green. It glowed. The baselines were whiter than the freshly done laundry in TV commercials. Pop and I settled in to watch batting practice. Then the old-timers were introduced. Some of them went clear back to the 1930s. Sal Maglie, Dodger nemesis when he played for the Giants, received a cheer. A lot of the players I’d never heard of, but they were warmly welcomed back to New York. And then the crowd hushed as Roy Campanella, the Dodgers’ legendary catcher, was wheeled to home plate. Five years earlier, Campy broke his neck when his car skidded on an icy Long Island road. He’d been in a wheelchair ever since. The crowd—Dodger, Giant, and Yankee fans— roared their admiration for the future Hall of Famer. What I most remember about that day, after Campy’s appearance, was the smell of Major League Baseball. First, you had cigarette and cigar smoke, pungent and biting. To that you added beer, yeasty and sour. Then there was the scent of aftershave and cologne on faces of the predominantly male spectators. To this day, when someone wearing Old Spice passes by, my nose goes back to that day at the Polo Grounds and dozens of games at Shea Stadium. If you want to understand how special Shea Stadium was to New Yorkers, watch the documentary Last Play at Shea. For me and my best friend, Scott, it was home away from home during my junior high years.

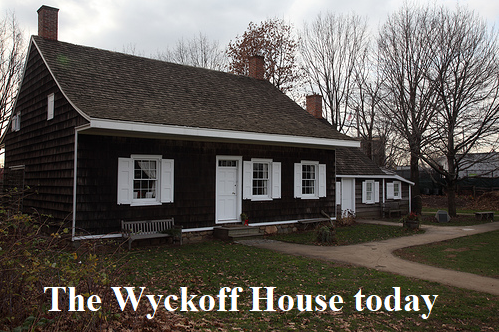

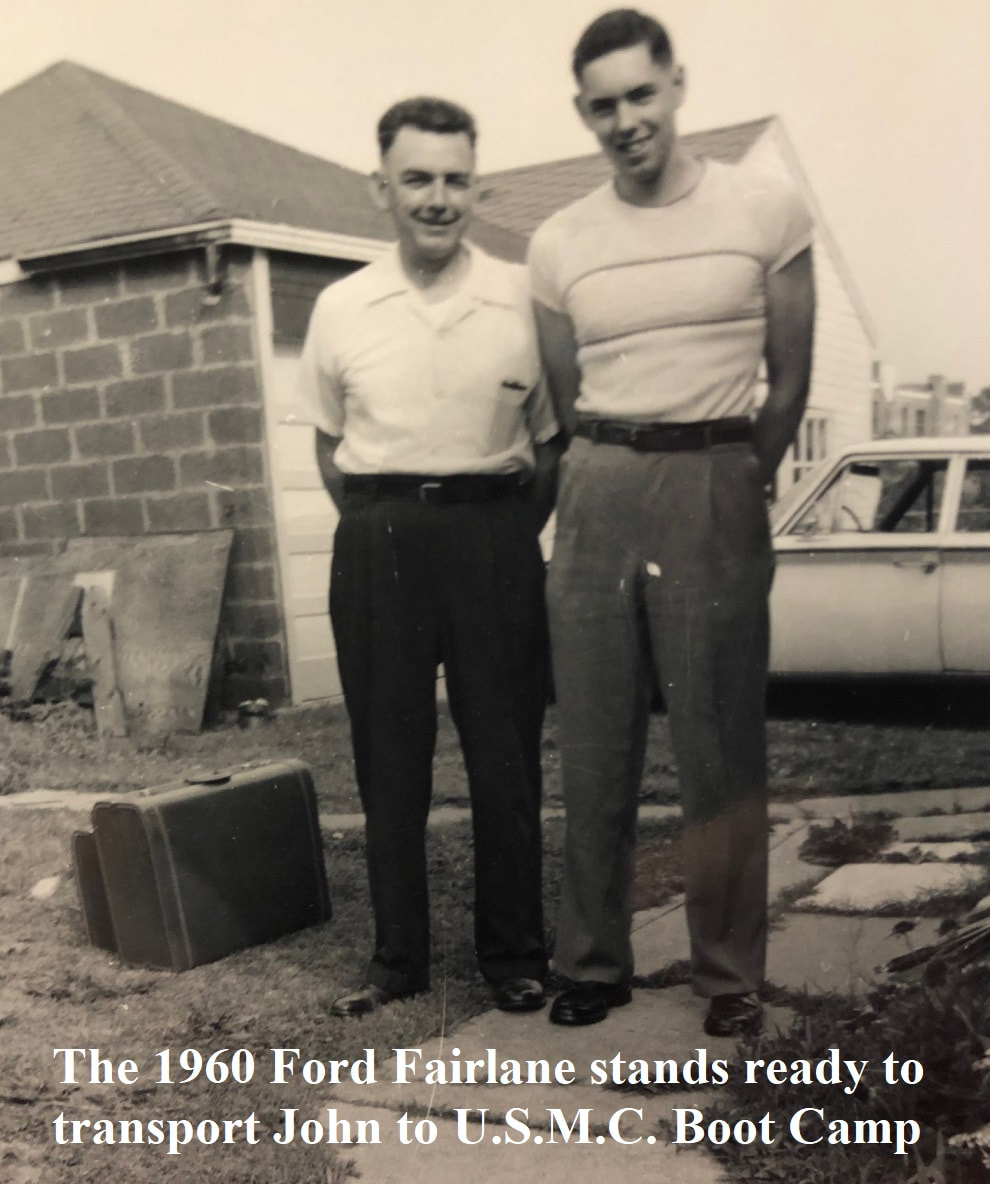

My favorite photo from the players’ lot featured then player-coach Yogi Berra. Yogi was a legend for his unique way with words, like the way he described a popular restaurant, “Nobody goes there anymore; it’s too crowded.” He was pretty frugal too. While other players drove into the lot in Monte Carlos and Cadillacs, I got a great picture of Yogi behind the wheel of his 1965 Chevy Corvair. We soon learned a Shea kids' secret. If you want to actually meet the players, you needed to wait before the game at the entrance to the Diamond Club. There the players walked in, having deposited their cars at a less conspicuous location than the players’ lot. We never waited after a game to talk with players. In the mid-sixties, the Amazins were still losing most of their games, and no one wants to talk to kids after a loss. So we’d intercept our heroes before the game, and with great success. I have autographs and wonderful photos of Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Jerry Grote and other Mets greats. Imagine if we’d been able to take selfies back then. The games themselves were often less than memorable; still, I bought a scorecard every time and meticulously charted every play. Pop taught me the art of scoring a game, and I believed his was the only right way to do it. Mr. Robins taught Scott the same technique. Some years later, when a bunch of us Bible college kids went to a Phillies game, I discovered there was at least one other way. It seemed Pennsylvania people filled in the box completely when a run scored. Pop and I merely completed our little diamond shape within the box. When I wasn’t at Shea with Scott for a day game, or in the box seats with Pop for a night game, I was often perched in front of our TV watching Ralph Kiner and Lindsey Nelson call the game for WOR-TV. A Sunday afternoon game in 1966, watched with John and Pop on our old Crosley, led to my first of three “athletic injuries.” The 1966 Mets weren’t as bad as in previous years, but they were still one of the worst teams in the league. And yet we loved them. We loved Ed Kranepool’s consistency at first base. We loved Ron Hunt’s ability to turn the double play. Above all, the Baisleys loved right fielder Ron Swoboda, even though he never lived up to the potential the team saw in him. That Sunday afternoon the Mets had battled back from a deficit. In the bottom of the ninth, they were down by only a run with a man on base. One of my favorite players, utility infielder Chuck Hiller came to the plate. He took the first pitch for a strike. Then, from the quiet of his easy chair, Pop’s voice rang out, “Watch him pole one.” Hiller was a man of few home runs, more of a scrappy singles hitter. Good bat in a clutch situation like he was in, but only because he’d likely not strike out or hit into a double play. He might even hit a double and bring the tying run home. “Watch him pole one.” With Pop’s words still hanging in the air, the next pitch came at Hiller. Crack! The ball sped from Hiller’s bat toward the outfield. And it kept going. As it cleared the fence I leaped from where I’d been sitting on the floor, totally elated. I came down directly on my right big toe, breaking the bone and damaging the nail. The next day, Dr. Scalise to a look at it and said the bone would heal okay on its own. However, I needed to have the ingrown toenail removed a year later. It was worth it. Read more about athletic injuries and their connection to my love for ice hockey and football in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Jim Scalia collected pennies; no, not in a Hoarders sense. Jim had painstakingly amassed one of almost every penny produced in U.S. Mints from 1909 until 1964. He’d been collecting Lincoln pennies for about two years, placing each one carefully in its proper slot in a blue numismatist’s book. By the time I’d gotten to know Jim he lacked only the illusive 1955S, the rare 1909S and 1910S, and the ultimate prize, the 1909SVDB, which contained the initials of its engraver, Victor D. Brenner. I remember the day Jim first showed me his collection. I think we were playing The Man from U.N.C.L.E. at his house. This was long before the age of cosplay. We just thought it was cool to dress in suits and pretend we were secret agents. I went for the black turtleneck look of Illya Kuryakin, and Jim went for the white shirt and tie of Napoleon Solo. Dark sport jackets for both of us. Some months later, Jim and I, still dressed as secret agents, joined the thirty other members of Mr. Remais’ Social Studies class in canvassing door-to-door throughout Canarsie for signatures on a petition to “Save the Wyckoff House.” The Wyckoff House was the oldest continually occupied Dutch house in the Five Boroughs, but it was in an advanced state of disrepair. Mr. Remais thought a class of 12 and 13 year-olds could save it. And we believed him. Jim and I had never heard of the Wyckoff House up until then, even though it was alleged to be located at the northwest edge of Canarsie, so we had to check it out. One day after school we set out from Jim’s house, in full Man from U.N.C.L.E. regalia, and trekked toward the location described by our teacher. We crept stealthily through a heavily-weeded area that looked like it might be hiding the old Dutch homestead. Just when we began feeling hopelessly lost, we entered a clearing and discovered a not-quite-overgrown drive. Creeping along the edge of the drive, but still under weedy cover, we made our way to the house itself. It was indeed occupied, but we’d seen enough and had no desire to meet any occupants who would live in such squalor. We returned to Jim’s house determined to get our petition signed and restore the house to its 17th century glory. Many days of canvassing followed, along with a letter-writing campaign to Brooklyn Borough President Emmanuel Cellar and Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Then we waited. It was during this seemingly endless wait that Jim showed me his penny collection. I was impressed. That night at supper, I told Mom and Pop about it. “Didn’t (insert some obscure relative’s name here) have something like that, Art?” asked Mom. “I think so,” said Pop. “Where is it?” I inquired. “Have you looked in your dresser?” Mom answered. My dresser? The suggestion baffled me. Why would I look in my dresser for something I didn’t even know existed? Why look in my dresser for anything? Mom washed and put away my clothes. She knew my sense of color coordination well enough to lay my clothes out before waking me each morning. God help the world if I dressed myself. I did try once in sixth grade. I put on a giant red and white polka dot Soupy Sales bow tie over a brown and lime green striped polo shirt. “Never again” Mom huffed. I rarely looked inside my dresser anymore. After supper, I went to my room to check my dresser. Yikes! There were more clothes in there than I thought I had. I gained new respect for Mom’s choices when I saw all the potential mismatches she contended with every day. But underneath each drawer’s layer of socks and underwear and polo shirts lay buried treasure. In one drawer generations of wallets lay interred. Some bore the marks of hard wear, maybe by a grandfather or great-uncle. Others were pristine. They were even more likely to have come from an ancestor—a dead one. Brrr. Why my dresser? The wallet drawer eventually yielded what is now a prized possession: an early 1950s era Brooklyn Dodger wallet. It was cheaply made, for kids not grandparents, but it was, and is still, beautiful. That wallet now lives in my current dresser drawer, under my hiking socks, waiting to be discovered by another generation. Beneath the neatly-folded t-shirts in the bottom drawer, next to the box containing leftover ration books from WWII, I discovered the penny books, two of them. One held Lincoln cents from 1909-1940 and the other from 1941-1959. When I asked Mom and Pop whose they were, something I figured they’d know since the collection ended so recently, they shrugged, “Who knows?” That’s the way it was at my house. Things—antiques and cheap trinkets—appeared out of nowhere. I carefully opened the first book. Very few spots were vacant. At that time I didn’t know the value of the coins to which I previously referred, so I called Jim Scalia. “Hey!” I said. “I found an old penny collection. Want to check it out?” Jim said, “Maybe later. What’s it got?” “Almost everything,” I answered. “Does it have a 1909SVDB?” “No, that space is blank. But it’s got everything else.” “Shit! I’ll be right over!” Jim arrived in about 20 minutes, not dressed as a Man from U.N.C.L.E. He looked over the coin books. Indeed, the only pennies missing between 1909 and 1962 were the 9SVDB and the 1955S, although the 1910S was too worn to have been of much value. Jim asked for a magnifying glass and, of course, Mom offered him a choice of modern or antique. He kept examining the 1909S and saying, “Shit.” He finally told me it was in at least very good (VG) condition and was worth $30-45. That’s in 1964 dollars. Not bad for a penny. He said a few of the others, like the 1911S, were worth a few bucks too. Jim and I stayed friends throughout junior high, going our separate ways sometime in high school. He never found his 1909SVDB. The Wyckoff House children’s campaign succeeded, and the house was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1967. I still have the letter from Emmanuel Cellar congratulating me on a job well done. I visited there a few years back, but not dressed as Illya Kuryakin. Guy Ritchie directed a movie version of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. in 2015, but it wasn’t as cool as the original TV series. I kept my penny collection until the early 80s. I sold it when I learned a pastor friend needed some help with a mission project. It brought about $90, mostly from the 1909S. New Yorkers love their sports teams. The Baisleys were no different, as you’ll discover in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Cars were an important part of life at Grace Church. Maybe it was because we “had a guy.” That guy was Ted Rowland. Ted owned a Ford dealership on Long Island. That’s why everyone in church drove a Ford. I don’t know if church members got better deals, or if Ted had just convinced them they were getting better deals. Either way, East 92nd Street, as it ran past Grace Church, sported a lot of Fords on Sunday mornings. Pop’s first car was a 1936 Ford, a Tudor. Tudor was Ford’s fancy way of telling potential customers it had two doors. The four door version was called—and I’m not making this up—the Fordor. Pop’s second car, a 1953 Ford, also a two-door, began my family’s often awkward and sometimes wonderful relationship with automobiles. On a sunny late summer afternoon in 1960, before my brother entered and dropped out of City College to join the Marines, he was hanging out with Karl Kriegel on his stoop. I was in the house, probably being babysat by Isaac in his apartment. I heard the thud; John saw it all. Mom had to run an errand, most likely a short trip to the drug store with one of the church ladies. After backing out of our driveway, the one on Isaac’s side of the yard, she slowly maneuvered the Ford across the street in order to face south. She wasn’t moving too quickly, John observed, but she backed up with a strong sense of purpose. When her right rear fender gently edged along the telephone pole, much the way the Titanic edged along the iceberg, she panicked and accelerated in reverse. Somehow, the other fender wedged itself against a fire hydrant, what old-time Canarsians called a “johnny pump” (although I don’t know why). That was the thud I heard. Isaac and I ran down the stairs and out the rarely-used front door to assess the damage. John and Karl stayed on the stoop a few doors down just taking it all in. It was quite a scene. Isaac took command as only an ancient mariner could do. He told Mom to put the car in first gear and slowly pull forward. Nothing. The car wouldn’t budge. Isaac switched places with Mom. Still no movement, just spinning wheels in the grassy strip between the sidewalk and the curb. Isaac gave up trying to save the fenders and went for the ultimate weapon: his crowbar. John and Karl continued watching. Isaac quickly returned with the crowbar. He instructed Mom to put the car in gear and try once again to pull forward slowly as he, as gently as possible, wedged the crowbar between the fender and the phone pole. Nothing about the process was gentle. He rammed the crowbar with the heel of his hand and then with his knee, gaining a little more purchase. Swearing quietly so Mom wouldn’t hear, he repeated the process. On his third attempt the Ford broke free, metal screaming against metal (the crowbar) and squealing against wood (the pole) as Mom not so gently drove away from her predicament. After the excitement died down, John and Karl leapt from their perch and walked to our backyard, where the ‘53 Ford lay mangled. John grabbed a tape measure from Pop’s tool box and proceeded to measure the rear section of the car. Then he and Karl crossed the street and measured the distance between the telephone pole and the fire hydrant. Measure once, shake your head; measure twice, keep shaking that head. Finally, John looked at Karl and said, head still shaking, “I don’t know how she did it, but she did it.” Mom was a fairly new driver back then, but her skills never did improve much. She never wrecked a car again, but she came close a few times. Fortunately, she never drove fast enough to do any damage. Mom always used her meager driving skills on behalf of others. Whenever a little old lady from Grace Church or a neighbor down the street needed a lift to the supermarket or the doctor or the drug store, they’d call Mom, and she never failed them. When it came to driving, Mom had the greatest of all abilities: availability. The Ford was repairable, but Pop decided it was time to replace it. He’d bought it used and figured he’d reached a level of success in life where a new car was both acceptable and affordable. The 1960 model year was just beginning, and Ted Rowland’s showroom was calling Pop to Long Island. Pop returned to Brooklyn with the receipt for his down payment on a brand new Ford Fairlane—the straight Fairlane not the fancier, and more expensive, Fairlane 500. Uncle Freddy drove a Fairlane 500, from Ted Rowland, of course, but he worked for New York Bell—the Phone Company—and Pop was merely a civil servant. So, basic Fairlane it was for the Baisleys. Not only was the Fairlane Pop’s first new car, it was his first car with four—count ‘em, four—doors. No more waiting in the rain for people to climb into the back before settling comfortably into the front seat. Four doors! Two decades of driving a car with only two doors may explain why Pop had trouble getting used to four doors. A few days later, after the good folks at Ted Rowland Ford had properly given Pop his money’s worth of “dealer prep,” he drove the gleaming white behemoth through the chain link gate on Isaac’s side of the yard to its new home.

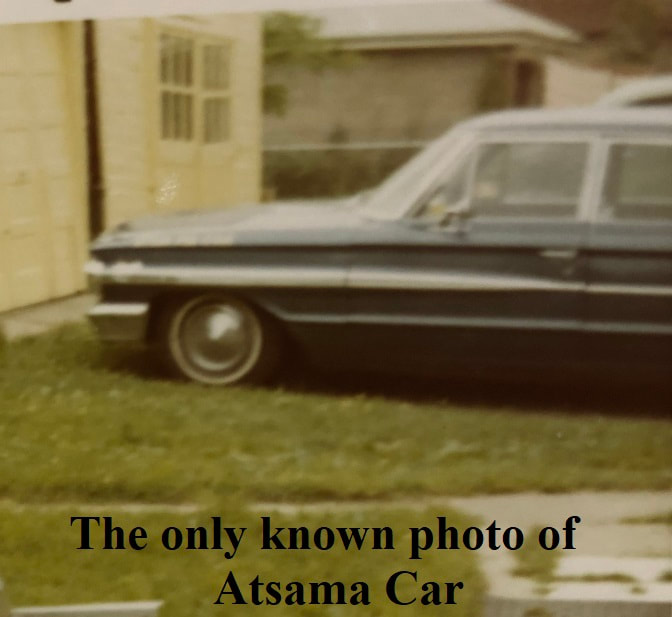

As John piled up A’s at Brooklyn Tech, Pop beamed with pride as the owner of a showroom-fresh 1960 Ford. He wasn’t beaming long before he went his first round against his ultimate nemesis, the gate. I blame those back doors, not Pop’s driving. One fall day, Pop took a personal day off from his job with the Labor Department to run an errand. It had to have been very important because he planned on driving. That was a rare event, Pop driving through Brooklyn streets. Or maybe he just wanted to cruise in his Fairlane. John usually took the bus and subway to school, but this day Pop was home and asked if John would like a ride. I know it sounds hokey, but I strongly suspect John answered something like, “That’d be swell, Dad,” or some such fifties-ism. After they, and Mom, got into the car, and Pop started it up, John volunteered to run to the end of the driveway and open the gate. He’d done things like that before, back when Baisley vehicles only came with two doors. Things had changed, however. John jumped out of the back seat, enjoying the ease of springing through the right rear door. He opened the gate and then crossed to Pop’s side of the driveway to wait for the Fairlane to back up. To this day he doesn’t know why he left the right rear door open or why he didn’t wait on that side of the driveway. He just did it. John never saw the door he’d left open. Pop never looked to the side. He just backed up with his turned head toward the rear window. The low speed crash came and went quickly, but the shock remained for days. “John, why did you leave the door open?” No answer would suffice. The Fairlane’s pristine beauty was no more. It was a sad day in Baisley automotive history, but not the saddest. That day occurred the following spring. It was morning, that much I remember. It had to be a weekend because Pop never drove the Fairlane on weekdays. Weekdays were what public transportation was for. So it had to be Saturday. Not Sunday, of course. We walked to church on Sunday, strolling as a family around Avenue K and up East 92nd Street if we had the time, running individually through the vacant lot just north of us if we were late. We were always late. Yes, Saturday morning wins by elimination. Pop needed to go somewhere, but first he walked to the gate and opened it. Then he opened the right rear door and placed something on the back seat. I hope it was an important something, but I don’t remember. I never heard the crash, I only heard the wailing. Grown men don’t cry, or so goes a popular early 60s notion. Pop cried. He moaned. He wailed! We could hear him as he walked from the driveway. His words pierced my soul, “I can understand once—once—but twice? Not twice.” The words staggered out in sobs. Pop had knocked off the same door that had been replaced only a few months earlier. The cries were because this time he had no one with whom to be angry, no one to blame. I blame the second set of doors. It was too much for a man of almost fifty to get used to. I think Pop blamed the Ford Motor Company. He never owned another Ford product. After driving the curséd Fairlane until 1963, he bought the first of his station wagons: a Chevy Belair. The gang loved it. Next came a ‘67 Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser, the wagon with the wraparound sunroof. After that a Dodge and a Plymouth. He was done with Fords. I wasn’t. When I was growing up, the legal driving age in New York was 18, but if you took Driver’s Education you could get your license at 17. The trick was, hardly any city schools offered Driver’s Ed in their regular curriculum. Some held the classes during the summer, but you had to pay for it. So it was that I came to learn the art of driving at a high school clear across Brooklyn, one to which I commuted every morning for two weeks during the summer before my seventeenth birthday. I learned quickly, even earning the right to drive myself home a couple of times, with the instructor as passenger. After the course, I practiced my skills with Pop at my side; he was a firm but gentle complement to the professional instructor. One fall day in 1969, I passed my driving test. I loved driving Pop’s ‘69 Dodge Coronet wagon. It had Chrysler’s small block workhorse, the 318ci V8. The car could leave rubber at any corner. Pop was proud of that. So was I. I can still feel the slight head jerk when I gunned the engine and popped the brake. Sweetness. Still, a high school senior needs his own car even in a city where most people use public transportation. Thanks to my inheritance from good ol’ Uncle Charlie, I had enough money to shop for something reasonably nice. Pop found it for me, a 1964 Ford Galaxie 500: dual exhausts, four barrel carburetor, and a 352ci engine. Nice. And four doors; the family curse. My first car had to have a name, and it was duly christened “Atsama Car” (say it fast with a Brooklyn accent and you’ll understand) by the Canarsie High track team. Affectionately known as “Atsama,” the Galaxie took my buddies and me everywhere. Most of the time I was a safe, considerate, and courteous driver. Occasionally I was not. One of Atsama’s talents was driving in circles; but don’t worry, he was always legally on the road. At the southern tip of Rockaway Parkway, where you entered or exited the Belt Parkway, there was a big traffic circle with a half-acre of grass in the middle. The idea was for drivers to gently transition from one road to another. Such devices go by names like “roundabout” and “rotary” in other parts of the country. While such circles are meant to be traversed only a quarter to three-quarters of the way around, one day, while driving Little Morty and Big Mike to Long Island, I decided it might be fun do go the full 360. And then 720. What the heck, 1080! Only Big Mike’s pleas about cops coming broke the cycle, and off we drove to Long Beach. Long Beach was our Dreamland. There awaited the fiercest chili, the biggest hot dogs, the fattest fries, and—and this is the “dream” part—the most beautiful girls just waiting for us to give them a ride in Atsama. After countless cruises up and down Long Beach Road, hours spent lounging in the Nathan’s parking lot, and many vain attempts at not looking desperate, for one brief, shining moment a couple of girls took us up on the offer of a ride home. We may have imagined a romantic interlude, but neither Morty nor Mike nor I were adept at such things. We gave the girls exactly what they wanted: a safe ride home. Casanovas we were not, but we did know, and were friends with, lots of girls. One of those friends, Karen Gordon, initiated me into the family curse. I liked Karen. I thought she was cute, funny, and smart. Those are criteria I still adhere to. Jen, my wife, is cute, funny, and smart; and I like her too. One spring afternoon during our senior year at Canarsie High, Little Morty, Big Mike, Karen, and I were driving in Atsama and had to stop on Rockaway Parkway near the subway station for Karen to run an errand. We were lucky to find a parking space right near the bank she had to visit. Being a fairly new driver in New York City, I was anxious to show off my parallel parking skills. Not all New Yorkers drive, but those who do can parallel park the asses off any other drivers in the USA. I truly believe that. Atsama and I pulled up partway beside the car in front of the vacant space. I turned my head all the way around, like a ventriloquist's dummy, and deftly backed into the space. Then I pulled forward to bring Atsama to a full parallel with the curb. All that was left was to back the Galaxie into a perfect center between the cars in front and behind me. Karen, apparently, didn’t understand the value of a perfectly parallel, perfectly centered automobile. As I began backing up, Karen thrust the right rear—yep, the accurséd right rear—door open. Thud! Rip! Atsama’s door tore almost all the way free from its hinges. “Karen! What are you doing?” I shouted. “I didn’t know you were going to back up,” she replied. And that was the end of the argument. What was done was done, and neither Atsama nor I were going to let a broken door interfere with a friendship. Karen apologized to Atsama; we all tied the door shut with some clothesline rope, and drove off after Karen ran her errand. She assured me she’d fix the door. A few days later, Karen appeared at my house with the right rear door of a yellow ‘64 Ford Galaxie. Little Morty, our car expert, attached it to Atsama, and he was whole again. Except Atsama was a deep metallic blue. The door was a matte yellow. What to do, what to do. Had I been an adult, or maybe just someone other than who I am, I would have taken the car to Earl Scheib for a cheap paint job. Not me. I bought a bottle of Ford deep metallic blue paint and a couple of brushes. For the rest of the school year, my friends, classmates, and track teammates painted their signatures on Atsama’s new door. It was better than a yearbook. In August, I drove Atsama onto the campus of Lancaster Bible College for the first time. He and I immediately felt the judging eyes of the faculty, upper class students, and their bland, sedate automobiles. Tough. Atsama’s named fenders and signed door, in gleaming blue and flat yellow, had more character than the lot of them. A few months later they opened a new shopping mall on the outskirts of Lancaster. “Park City” they called it. Some college buddies and I decided to check it out one day after class. Entering the highway, Atsama’s accelerator pedal stuck. He sped helplessly along as the speedometer reached 100. Brakes wouldn’t stop him. Finally, not knowing any better, I turned off the engine, out of which came a weird clunking sound. Safely on the shoulder of the highway, we got out of the car. A bright brown liquid flowed freely out of the underside of Atsama’s engine. We had him towed to a family friend’s barn where we attempted, over the next six months, to replace the blown engine, that beautiful old 352. We never got it right. I don’t know if the farmer who inherited Atsama ever got him running again. Sometimes I still miss the great blue beast. Cosplay is big these days, with Comic Con and other –Cons drawing thousands. Cosplay just might have had its beginning with some junior high kids from Canarsie, as you’ll see in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I read the words “jelly glass” and “sugar sandwich” the other day, in someone else’s memoir. The writer was describing being poor in Houston in the 1950s. That took me back to my own childhood experiences with jelly glasses and sugar sandwiches. In Canarsie, we drank out of jelly glasses at our regular meals. Jelly glasses were the jars jelly came in, usually decorated with scenes from Howdy Doody, Yogi Bear, or other cultural icons. You bought the jelly, and the jar was free. A lot of people on East 93rd Street drank out of jelly glasses. We also ate “bread ‘n sugar.” It was a real treat when Mom would take a slice of bread, coat it with a thin layer of butter, pour some sugar on it, and cut it into four pieces with the crusts off. Wow! Every once in a while we’d have “bread ‘n honey.” It was the same basic treat but with honey instead of sugar. And Mom didn’t cut it up, so the honey wouldn’t ooze everywhere. I loved bread ‘n honey. I thought that meant we were living like kings. Maybe we were living like kings; we owned a palace free and clear, with two yards if you count Isaac’s half. You could stand at the front fence and look back to the tree line that separated our property from the House of the Rising Sun’s parking lot, and you’d think you were looking across Jamaica Bay. I remember the first time I heard Richard Harris sing Jimmy Webb’s The Yard Went On Forever. There was a frying pan And she would cook their dreams while they were dreaming And later she would send them out to play And the yard went on forever That was our house. That was 1304. We were rich! But we ate Spam sandwiches. We enjoyed sardines right out of the can. Dessert was a drop of honey on lightly-buttered white bread. And the yard went on forever. Food was a cultural expression in Canarsie. You could walk around on Thursday afternoon and the smell of baking lasagna seeped into your nostrils. On Fridays half of East 93rd Street smelled like the Fulton Fish Market. The scent of gefilte fish and other Jewish delicacies completed the olfactory world tour. On the Parkway and other major streets, fresh-baked bagels and bialys competed with pizza and veal parmesan sandwiches for nose space. At our WASPish house it was more like pot roast, baked chicken, and pork chops. We’d have steak every once in a while, but it never tasted as good as at the Flame. I think it was the cut of beef. Mom pounded and pounded the meat, but it was never quite to submission. Still, it was steak, which not all our neighbors could afford. We ate our dinner every weekday evening at 6:00. That was ten minutes after Pop arrived home from his office in Manhattan. I don’t recall Pop demanding that dinner be served precisely the same time each evening, but that’s when he got there and that’s when Mom had the food ready. Saturday was different. We ate around the same time, but in the summer Pop might cook on the grill outside. In other seasons he’d make pancakes or waffles on Saturday nights. Since we’d often go to Grandma and Gramps’s house after church on Sunday, Mom pretty much had weekends off. We ate on blue-green melmac plates using stainless flatware. We drank out of jelly jars and white glass coffee cups. In the summer, Mom brought out the “deer” glasses for iced tea. They were tall green glasses with white images of deer on them. I’ve drank a lot of iced tea over the years, but none tasted as good as the stuff in the deer glasses. They had their own coasters too; pale blue lids that proclaimed the cottage cheese they originally packaged. I’m not sure Mom ever really bought a drinking glass. As did many Canarsie women, Mom had inherited a set of china and a box of silverware from her mother. It came out at Thanksgiving, at Easter, and on whatever Sundays we didn’t go to Grandma's. It didn’t mean we or my grandparents were rich. It’s just what people had in those days. My brother inherited the silverware. I got the china, which I’ve since passed along to my daughter. People don’t have much use for china and silver anymore. We ate at home a lot more than my family does now, but that doesn’t mean we never went out. Sometimes on Sunday, half the church would pack into Lum’s Chinese restaurant. Occasionally, Pop would spring for a trip to Wetson’s or Farrell’s for hamburgers. I went to P.S.114 with one of the Farrells, so that made it more cool. The biggest treats, however, were White Castle and Sears. No one ever believed White Castle’s claim that what’s in their tiny burgers is 100% beef. It doesn’t taste like beef; it tastes like, well, it tastes like White Castle. I find nothing inherently wrong with that. It’s a good taste; for me a down home taste. New York kids, and probably those in Chicago and St. Louis and Indianapolis, made White Castles a rite of passage. When you could down a dozen at one sitting, you entered manhood. Keeping them down was not required. Lunch at Sears was an even bigger treat than White Castle, at least for me. Our nearest Sears Roebuck—they went by the full name back then—sold hot dogs cooked on stainless steel rollers. They came out perfectly brown all the way around, and they were fully cooked inside without being hot enough to burn a young mouth. In short, they tasted exactly like a hot dog is supposed to taste. Only one thing could make a Sears hot dog better; and Sears, which sold just about everything, had that one thing: a giant keg of Hires root beer. No flavors ever blended as well as a Sears hot dog, yellow mustard, and Hires root beer from an artificial wooden keg. School lunches fell far below the status of “treat.” For one thing, I was the proverbial “picky” eater. Mom learned the hard way that it was best just to pack the same thing in my Roy Rogers lunch box every day. (I’d stopped eating school-cooked lunches after the hat-in-the-soup incident.) One year I ate nothing but peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. For two whole years I ate only liverwurst sandwiches. How could anyone be considered a picky eater if he ate liverwurst? While in elementary school at P.S.114, there was one break from the lunches Mom packed for me. Occasionally, I’d have to walk to Grandma’s for lunch. Perhaps Mom had someone to drive to the doctor or supermarket that day, and she didn’t have time to pack the liverwurst. On those days, Grandma was the backup. Bologna sandwiches were her usual fare; or sometimes tuna fish. They were always paired with a little dish of mandarin oranges. I didn’t know they had a technical name. I just thought they tasted oddly sweeter than the oranges I got in my stocking at Christmas time. I still have weird feelings about them, at least the ones that come in the cans like Grandma used to open. New York City has a well-deserved reputation for being a center of world cuisine. Each neighborhood has its own culinary niche. There’s Chinatown, Little Italy, Hell’s Kitchen. Okay, you may not find diabolical dishes there, but I’m sure you’ll find some great places to eat. My brother’s neighborhood in Queens features some of the best Caribbean food north of Montego Bay. The aromas emanating from each neighborhood reflect the best of its cooking. If you had walked down any of the major thoroughfares of Canarsie in the 1960, you’d have encountered two distinct scents: bagels and pizza. You can’t find real bagels in the refrigerated displays at the supermarket. As much as I love my favorite bagel shop in Richmond, Indiana, what they serve there is not what they sell at any bagel bakery in Brooklyn. New York bagels are boiled before baking, the texture taking on the chewy-crispy consistency for which they are known. If topped at all it’s with the simplest of ingredients: salt, poppy or sesame seeds, or onion. You eat them with schmear—cream cheese for purists, and maybe with lox and capers if you’re really hungry. I love my Indiana bagels, don’t get me wrong; but if I ordered a sun-dried tomato, Asiago cheese, or pumpkin spice bagel in Canarsie I’d be laughed all the way to Gowanus. Salt bagels were my standard fare. Every day during eighth and ninth grade I ordered two salt bagels from the shop across Flatlands Avenue from Bildersee Junior High, and I washed them down with a chocolate shake from the Carvel next door. Never tired of that combo. I’d eat it again in a minute, perhaps with only one salt bagel to go with my shake. I’m not that skinny kid anymore. I have similar feelings about “real” pizza. You can get real Chicago pizza at a Chicagoland pizza place. I will never begrudge Chicago that distinction. But the only other real pizza in America is found in New York City and in a few places in Philly. Again, I don’t want you to think I avoid other-than-NY pizza. We have a small chain in eastern Indiana called Pizza King. They serve a somewhat overpriced but delicious pie topped with a spicy tomato sauce, just the right amount of cheese, and some great toppings. It tastes wonderful, but it’s not real pizza. It’s the crust. American pizza chains have tried everything to make their crusts more palatable. They add garlic. They stuff their crust with cheese. I’m sure somewhere there’s a pretzel crust pizza. But without the gimmicks their crusts are tasteless. New York pizza crust tastes like… it tastes like pizza crust. It has a flavor. If your sauce or toppings don’t make it from one edge to the other you don’t complain because those last bites of pure crust are more than edible. You can still taste pizza in them.

Armando’s was also the scene of a quintessential New York parking space theft on the day some years ago when I took my kids to their dad’s old haunt. I needed to go east on a business trip when Stephen and Kellyn were still young enough to care where Dad grew up, so I flew them to New York with me. We found Armando’s to be exactly as I’d left it 25 years earlier. Armando still owned the place. Everything was as delicious as I’d described so many times to my family. As we were getting ready to leave, a white Chevy was preparing to exit its parking space right in front of the restaurant. What happened next is pure NYC. As the Chevy got ready to edge into Parkway traffic, a silver Toyota stopped to let it out and to claim its prized space. The Toyota exercised uncommon patience as the Chevy slowly pulled away from the curb. The red Mazda Miata behind the Toyota was not so patient. When the Chevy was gone and the Toyota pulled next to the car in front of the open space, preparatory to executing a perfect parallel park, the little Miata jumped the curb—the sound of undercarriage grating against the concrete—dashed across the sidewalk, and dove headfirst into the unoccupied space. The Toyota jammed on its brakes. Words and fingers were exchanged, and then the silver sedan sped up the Parkway, most likely planning its revenge against the next little red sports car it came upon. Stephen and Kellyn just stood there taking it all in. I beamed, never so proud to be their dad, or a New Yorker. The Baisleys’ automobile of choice was the humble Ford. From Pop’s 1936 coupe to my 1964 Galaxie, we were a Ford family. Sometimes that spelled trouble, as you’ll see in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed