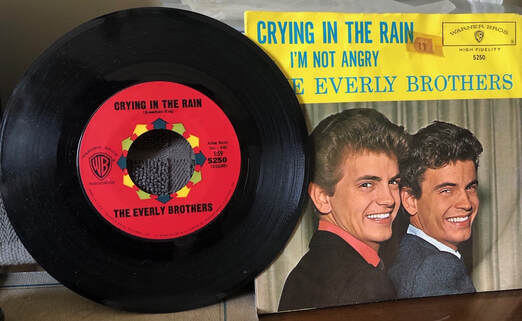

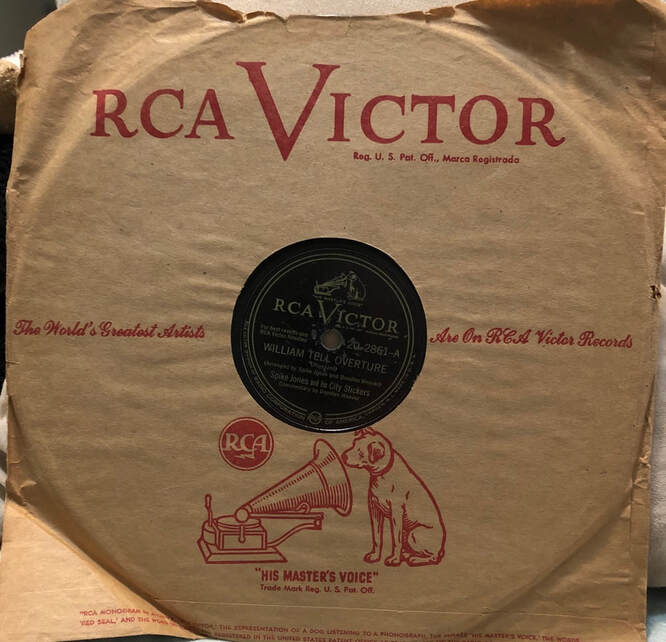

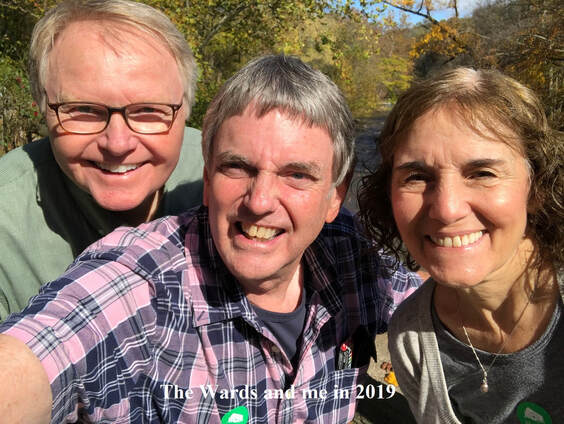

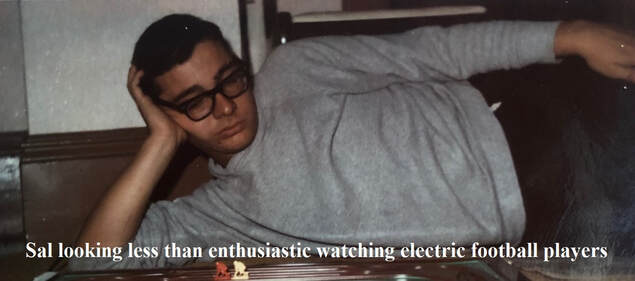

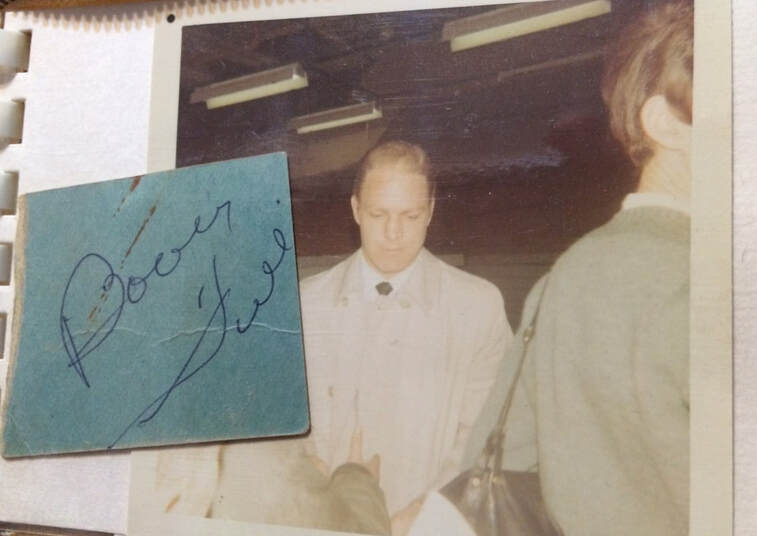

Tales of a Canarsie Boy, Episode Thirty-one: Music Is Life--Blueberry Hill to Little Deuce Coupe9/25/2020 Harry Chapin describes the obsession of a certain Dayton, Ohio, drycleaner in his song, Mr. Tanner. Of Tanner, a popular singer at local venues, Chapin said, “Music was his life.” I know how the fictional Mr. Tanner felt. While my life has been filled with religion and its commensurate guilt, with love and its share of heartbreak, and with friends and acquaintances I will never forget, mostly my life has been made up of music. Some people say their life should have a soundtrack; perhaps mine had a score. The first movement began offstage sometime in the 1930s when my dad, his brother-in-law Hank, and two other young men from Grace Church formed the Grace Gospelaires. From then almost until his dying day Pop was singing. Hymns, gospel choruses, opera, standards, and showtunes filled his repertoire. He sang in the shower, in the kitchen, and while cutting the grass. I’m sure, along with Mom’s sweet alto voice, Pop’s tenor glided into my ears as soon as they were formed. It wasn’t long until I caught the tune bug. I learned the children’s choruses we all sang at Grace Church in the fifties: Jesus Loves Me, Jesus Loves the Little Children, Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam. The Sunbeam song never made much sense to me. I never saw a sunbeam. I drew sunbeams coming from every sun in my watercolor and Crayola masterpieces, but they beamed in my imagination. Maybe not even my own imagination. I think sunbeams are drawn from a collective child-consciousness. That’s why they all emanate so perfectly from every sun, whether the child uses purple crayons, yellow finger paints, or pink watercolors. But no one really sees them, and who would ever want to be one—pressed for all time on a sheet of white paper. I sang along with the other kids in Sunday school, but my love of singing really began when I started memorizing songs my brother listened to late at night on his little Philco table radio. The first song I recall hearing on that radio was Fats Domino’s version of Blueberry Hill. Something about the way Fats articulated every one of the first four words so succinctly: I. Found. My. Thrill. I can still hear it clearly after sixty-plus years. I remember Buddy Holly’s Peggy Sue too, but only because his staccato Sue-uh-oo grated on my preschool ears. By the time I entered P.S.114, I’d developed a taste for Top 40 music and began adding to my repertoire. The first song I sang in public was Burl Ives’ A Little Bitty Tear. I was sitting in the rocking chair at Grandma and Gramps’s house on East 94th Street on a Saturday night. I don’t know why, but I felt like singing; so I did: A little bitty tear let me down Spoiled my act as a clown I had it made up not to make a frown But a little bitty tear let me down Why did I learn that song? How melancholy must an elementary school kid be to want to sing about a guy whose true love is walking out the door and he’s trying to hold it all together? I was a hopeless romantic before I knew those words went together. After taking requests for Little Bitty Tear Saturday after Saturday for a few months, I finally learned another song: Crying in the Rain by the Everly Brothers. Can we identify a theme here? Grandma’s rocking chair evoked emotions throughout my childhood. From the exuberance of a preschooler bouncing up and down while singing the Mickey Mouse Club theme to the gut-wrenching tween singing about raindrops mingled with tears, that rocker summoned my deepest feelings and expressed them through music. I guess my feelings during my preteen years were feelings of loneliness, maybe a fear of abandonment by someone who loved me. I did, after all, admit to having no friends, only acquaintances. Why did I claim that? I had Judy and Kurt. I had Scott. Was I so afraid I’d lose them that I couldn’t bear to call them friends? Looking back to my earliest years, and then through high school, I can convince myself I had few deep relationships. But the wonder of social media has returned some of those “acquaintances” to my life. They tell another side of the story. So many times in recent years a face I haven’t seen since Canarsie days shows up in social media and mentions the impact I had on their lives. Apparently more people knew me than I realized. I wonder how things might have turned out had I believed in the love I was receiving every day. Maybe I’d have spent less time in the rain. Along with listening to the radio, which brought about dramatic changes in me during my last two years in high school, I also listened to records. It began in Uncle Freddy and Aunt Barb’s basement. Uncle Freddy’s collection of 78 rpm albums was small but legendary. It featured hits by Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians, Gene Autry, and Arthur Godfrey. My favorites were the songs by Spike Jones and his City Slickers. I loved their parodies so much that Uncle Freddy actually gave the box of 78s to me when they moved to Florida. The whole Gang would come over to hear and laugh at Jones’ tongue-in-cheek takes on Cocktails for Two, My Old Flame, and the William Tell Overture, aka the Feitlebaum song. That was the song about a horse race featuring such memorable lines as “it’s cabbage by a head” and “banana is coming up to the bunch.” Eventually the long shot, Feitlebaum, proves victorious. It’s a comedy classic. I still have Uncle Freddy’s copy. I began accumulating my personal record collection some years before Uncle Freddy’s gracious gift. My first LP was Let’s All Sing with the Chipmunks. I was thrilled when I discovered it under the tree on Christmas 1959. I received the second Chipmunk album for my eighth birthday. The next Christmas I added Around the World with the Chipmunks. Judy, Kurt, and I learned all the songs. Our favorite was the one about the Japanese banana. Spoiler alert: according to the song, no such fruit exists. My friends outgrew the Chipmunks by the end of the school year. I stopped playing the albums, but the songs sang in my head for...well, I guess Japanese Banana still sings up there from time to time. Although the Chipmunks dominated my LP collection into the 60s, I had already started accumulating my 45s. 45 rpm records revolutionized the music industry. Whereas 78s were made of brittle shellac and easily broken, vinyl 45s were durable enough for teenagers to play at parties where they might not be as careful with them as their parents were with 78s. They were also cheap and smaller than any other record.  My first 45 was my favorite song, the aforementioned Crying in the Rain. I still have that record too. Then, in 1963, I discovered The Beach Boys. I can’t say I liked their music on its own merit, at least not at first; but I listened to The Beach Boys and begged my father to buy me the 45 with Shut Down on one side and 409 on the other. Pop was my main source of records before I could afford my own. If I was lucky, he’d stop at Sam Goody after work and grab the one I wanted. Why Shut Down? The most basic reason of all for an eleven year old boy: everybody else had it. Maybe they did and maybe they didn’t, but soon enough I did. That Christmas I became a true Beach Boys fan. I asked for, and received from Santa, the Little Deuce Coupe album. I have to admit I did not put Little Deuce Coupe at the top of my list due to its title song—I’d never heard it before obtaining the album. I requested it because Shut Down was on it. I might have been a bit obsessed with that song. Maybe it had something to do with my being an avid model maker, and that was the era when Big Daddy Roth’s Outlaw model car kits by Revell were popular. I made the “Rat Fink” and the “Mr. Gasser” cars among others. So, even if I had no aspiration to road or track, I was into car stuff; and Shut Down, along with 409 and Jan and Dean’s Little Old Lady from Pasadena and Dead Man’s Curve, were car stuff to the max. I opened my Little Deuce Coupe vinyl on Christmas morning, and I took it with me to Aunt Midge and Uncle Paul’s in Lynbrook, where the Baisley clan was having its annual gift exchange. I knew Uncle Paul had a decent hi-fi, and he might let me play some Beach Boys in the guest room with the door closed to keep the rock & roll from corrupting the Christians. That’s where I discovered there was more to the Boys than cars and surfing. Three songs from the Little Deuce Coupe album grabbed and held my attention. The first was Spirit of America. That song was, indeed, a car song, but it was a tribute to Craig Breedlove who, for a while held the coveted Land Speed Record (LSR). The Spirit of America was one of his record-setting vehicles. But that’s not what grabbed me; it was the melancholy tune. The song evoked in me a memory of a sad article I’d read in the Reader’s Digest a year or two earlier. (I’ve always had an uncanny memory for magazine and newspaper articles from the near and distance past.) This article was about the tragic LSR attempt by Athol Graham. Athol Graham was a Salt Lake City native who dreamed of conquering the Speed Record at the historic Bonneville Salt Flats of Utah. With ample skill and determination, but not an adequate vehicle for the attempt, Graham’s car crashed at 300mph, killing its driver. It was one of the saddest stories I’d read up to that point in my life. The way The Beach Boys sang that emotive tune by Brian Wilson brought all the pathos of Athol Graham back to my memory. A second song on the album continued the “tragic young man” theme. It seems The Beach Boys recorded their own take on Bobby Troup’s song about star-crossed lovers, Their Hearts Were Full of Spring. The Boys rewrote the lyrics as a tribute to James Dean, calling it A Young Man Is Gone. The song just about made me cry, even though up to that point I’d never even heard of James Dean or how he died. Now I live maybe an hour from Dean’s hometown and burial site. Heck, he was, and now I am, a Quaker, of all coincidences. But the song about a young man gone too soon became like a portent to me of an early demise. I often told people I didn’t think I’d live past 30. Finally, Little Deuce Coupe included a song that made me look at an old enemy in a new way. That enemy was school. By this time I was in sixth grade—top of the heap at P.S.114–I was a hallway Guard, although still rail skinny and non-athletic. But school was a place I mostly dreaded, the best part being the walk home with Blaise and George, or a visit to Mark’s house. Classes I could do without; and I was more than ready to depart the old brick school on Remsen Avenue forever. And then The Beach Boys gave me a reason to love the place. According to rock & roll lore, and Wikipedia, Brian Wilson and Mike Love wrote Be True to Your School as a tribute to Hawthorne High School, Wilson’s alma mater. Be true to your school Just like you are to your girl I never had a girl, but I planned to be absolutely true if I ever did have one. But a school? Man, school was where I was bullied, outrun, outplayed, and even outdone in grades—slightly—by other kids. Be true? Well, if The Beach Boys, who knew about things like cars and girls and surfing, said it, then it must be good advice. I decided, on that Christmas afternoon in 1963, that I’d give P.S.114 my best shot, and my whole heart, for my remaining semester as a student. And I did. As a matter of fact, I even won the heart of my teacher, the meanest one ever to walk P.S.114’s hallowed halls, with an essay about the next musical turn in my life: the Beatles. In the mid-1960s, four Liverpool musicians led the “British invasion” of America. I fell in line with Sgt. Pepper and marched with the Beatles through my early teen years. You’ll read about it in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Tales of a Canarsie Boy, Episode Thirty: Love, or Something Like It, Part 2—The Grandest Gesture9/21/2020 My initial date being a fiasco, I decided to avoid the practice most of my adolescent life. Still, there was something about hanging out with some members of the opposite sex that I just liked. I could confide anything in them. I knew they cared and they knew I cared. There’s romance in that, yet without romance. That’s the way it was with Faith, too. Faith lived next door to Aunt Barb and Uncle Freddy on Ocean Avenue in Lynbrook, Long Island. Her bedroom was on the second floor of her house, exactly parallel to mine, which was on the first floor of Aunt Barb’s. We got to know each other shortly after Faith’s family moved in. From then on I still loved Aunt Barb and laughed loudly at Uncle Freddy, but I found a friend in Faith while tolerating Adam, her little brother. Faith was beautiful, quick-witted, and Japanese, which to 12-year-old me meant she was exotic. We spent almost every minute together the three or four times each year I’d visit my aunt and uncle. On countless nights, Faith and I opened our windows and talked until all hours as if there were not a story, and about 15 feet of lawn, between us. We, and Adam, and some other kids, would walk to a nearby park to play on the swings and self-propelled merry-go-round. (What do they call those things?) We’d walk to Zinetti’s for ice cream sodas when we had the money. One day, Faith’s family took me to Rockaway Beach to spend the day at their restaurant. My first thought was, Japanese! Exotic! It was actually just a hamburger joint, a lot like the one in Bob’s Burgers, but it was fun hanging out on the boardwalk all day with Faith and Adam. My second date occurred the afternoon Faith said, “It’s hot today. Let’s go to the movies and see Bye-Bye Birdie. It’s my favorite movie ever!” And away we went; oddly, with no Adam in tow. The World of Henry Orient, an adorable lesser-known Peter Sellers movie led off the double feature. Then Bye-Bye Birdie proved to be a lot of fun. The rest of that week Faith and I practiced the dance moves. My only two dates in junior high school, and so different. Was it my crush on Gail that ruined the library date? Was it my crushless, lustless I-think-you-are-beautiful-but-more-amazing-as-a-friend feelings toward Faith that made a movie merely the jumping off point for lots of laughs? Damned if I’ll ever know. I wish I could arrange a reunion with Faith. I bet we’d break a bone or two trying to dance to Birdie. That’ll never happen. Working at a friend’s family’s Carvel store one night in 1969 someone showed me a newspaper obituary. “Didn’t you used to know a girl from Lynbrook named Faith? Shit! She walked in front of a train.” I don’t know why she did that, but I hope she’s still dancing. I didn’t go on another date for five years, and, at the time, I didn’t feel I was missing anything. All the other guys and girls were getting their hearts broken. Not me. I did have a part in some relationships, however. Once I started writing songs and poems, guys would ask me to come up with just the right words or verse to impress their girlfriends. Cyrano incarnate! Still I remained dateless. There was one other time in junior high when I almost made a connection with a girl. Of course it didn’t work out. I thought at the time it was because I was shy; maybe I was just clueless. Because the names Baisley and Blank are so close alphabetically, I often sat next to Joyce in class, especially in homeroom two years running. Joyce Blank was very pretty in a wabi sabi way. All her imperfections made for a very attractive package, which, of course, meant she was too good for me. Or so I thought. One day in eighth grade homeroom, I saw a hand slip a note into my desk. Odd, no one had slipped me a note since fourth grade, so long ago. I read it. “Do you LIKE me?” The hand and the note were from Joyce. Did I like her? Well, I’d dreamed for two years that we might have an actual conversation. Did I like her? Okay, she wasn’t Gail, but I’d messed that up beyond repair. Did I like her? Yes, I think I did, which is why I panicked. What if she was only asking because she thought I actually liked her and she wanted to be sure before she told me to bug off? What if she was just trying to relieve the boredom of homeroom? The thought that she might be revealing a liking of me—skinny, ugly me—never crossed my mind. At best, I might have said something like, “You’re okay.” At worst I might have ignored her for the rest of the year and my life. I honestly don’t remember, but don’t expect to find her in these pages again. Maybe I was more clueless than shy. My adolescence continued to pass undisturbed by girls. I graduated from Isaac Bildersee Junior High School in 1967 and moved on to the recently-constructed Canarsie High School. There I kept admiring attractive girls from afar, and helping other guys win their hearts, but I remained outside the dating crowd. That all changed one night in the summer of 1968. The summer before my sophomore year of high school, Billy Walker helped me get a “real job”; he recommended me to Morrie, the co-owner of a local drug store. I started high school somewhat gainfully employed. I walked the eight and a half blocks to work most days, and occasionally rode my bicycle. Generally working from 4:00-8:00, closing, I always enjoyed the walks home through the streetlight-illuminated Canarsie streets. During the summer, I’d plan my walks for when some of my favorite church ladies were on their porches or in their tiny gardens out back. Weird, huh? A fifteen year old “gang” member hanging out with little old ladies. But I liked them. They treated me like an adult, fed me all sorts of good stuff, and they told me stories of when they were fifteen, back before “the War,” which we all knew didn’t mean Vietnam. Helen Van Houten lived on East 94th Street a few blocks south of my grandmother. Inside Grace Church she was a tiger, enforcing her strict code of behavior on us kids. At home in her backyard, the summer sun dwindling after my shift at the drug store, Helen was a pussycat. She was sweet, kind, and a great conversationalist. A lot of my walks home included a stop at Helen’s. One night, as I let myself through Helen’s gate and made my way to the glow of the Coleman lantern she kept on a wrought iron table out back, I noticed two shadows in the lamplight. Helen had company. She welcomed me and mentioned to her guest that I was the one she had told her about. Helen’s company turned out to be Clair, a nice-looking girl a year older than I. Turns out Clair’s dad had been pastor of Grace Church for a few years in the 1950s. As a matter of fact, I was born the day Clair’s family moved into the Grace Church parsonage. Clair’s family had kept in touch with Helen over the years, and Clair had come from Buffalo to visit. Sweet, dangerous Helen had known all along that Clair and I might hit it off. After a little small talk, Helen excused herself and told us not to stay out too late. We stayed up until Helen had to come back out and tell us to call it quits. The next night and the next night it was the same. I can’t recall a single thing we talked about. I only remember every topic was fascinating. I’d never experienced anything like that before, not even with Judy. And then she was gone. Clair and I promised to write each other. Well, you know how kids are when they think they might like each other. Most of the time, the letters are never written, and certainly never sent. We wrote ‘em and we sent ‘em at least once a week. Even our letters sounded like conversation around a Coleman lantern. God, it was an awesome feeling. The week at Helen’s was in June. By July I was ready for a Grand Gesture. Heading into my junior year at Canarsie High I was alone again. This time, however, I had a… What did I have? Did I love Clair? I never even hinted that to her. I don’t know what emotions she might have felt toward me, but that didn’t matter. We both enjoyed each other’s company whether in person or on paper. So maybe she wasn’t my girlfriend, but she was mine. Flush with cash from the drug store and a heart way bigger than my brain I came up with the ultimate means of showing Clair just how important she had become to me. But it would require some secrecy, stupidity, and a ride to the airport. The stupidity I had in spades. For the airport ride I needed a guy with some knowledge of air travel. Billy Walker had read up on flying, and he had heard there was such a thing as student discounts by air carriers. He said all you had to do was present some identification at a ticket agency, fill out an application, and in a week or so you’d have a student ID for air travel. It worked! Soon, armed with my wad of cash, Billy’s knowledge of all things aeronautical, and enough gas to get us to and from Kennedy Airport, off we went to purchase a ticket for Buffalo. Yes, Buffalo. The Grand Gesture was to be an unannounced visit to Clair. Now for the secrecy. Billy swore he’d never tell anyone, and he didn’t. The airline’s customer service person sold me a window seat, LaGuardia to Buffalo, cash, no questions asked. Why LaGuardia? I knew that airport was near Shea Stadium, which had a subway stop. I could walk from the subway to the airport, I figured. Ticket purchased, partner in crime safely silenced, I waited until the appointed day of departure. Did I have a detailed plan in mind? Alas, no. I didn’t even know the location of the town where Clair lived, other than it was somewhere east of Buffalo. I just assumed I’d find it. I’d been in training for this mission for over a year, taking longer and longer walks out to the Island. My brother had done the same walks while in high school and after returning from the Marines. I tried to outdo him, one time walking all the way to East Meadow, a distance of 22 miles. For the Grand Gesture, I’d be walking from the Buffalo International Airport all the way to a place called Elma, somewhere east of someplace. I imagined it to be about 15 miles. I was ready. The big day arrived. I acted completely normal, which should have tipped Mom off that I was up to something. I had my ticket and a couple of changes of clothes in a small duffel bag. I’d even used Pop’s AAA Travel Guide for New York to book a room that night at the Holiday Inn. You didn’t need a credit card back then. My word as a gentleman was good enough since I’d be paying cash. Mom was home, and, being a Friday, Pop was at his office. With any luck, I’d be checked into the hotel before they even missed me. I made the plane on time, although the walk from the subway station to the airport was longer than I anticipated, and closed my eyes for a nap during the short flight. When I arrived in Buffalo, it was still early. Just time enough to get to the hotel before Pop got home and Mom wondered why I wasn’t at the dinner table. I found the Holiday Inn on the little map in the AAA Guide. Not knowing I could have called for a free shuttle ride, I walked the mile or so to the hotel and checked in without a problem. Then I unpacked my duffle and went to the bathroom. It was perfect, the trip so far and even the bathroom. There was a phone in it. I’m not kidding you. There was a freakin’ phone on the wall of the bathroom. Perfect. I sat down and dialed my home number. I had my story down pat. “Mom, could I talk to Pop for a minute?” “Where are you? You sound like long distance.” “Yeah, Mom. That’s what I want to talk to Pop about.” “Hey, Pop! Hey! I got a chance to see the Buffalo Bills practice tomorrow. Can I go?" Man, I was smooth. I had it all planned out. “No, Pop. In Buffalo. That’s where I am.” “[Expletives deleted.]” “I flew up to visit Clair. Figure I’d take in football practice tomorrow. It’s on the way to Clair’s house. Then I’ll get there midafternoon.” My smoothness was intoxicating. “No, Pop, they don’t know I’m coming.” “Get back home on the next flight!” yelled Pop uncharacteristically. I said I would and then hung up the phone and flushed. A few minutes later Pop called back. He’d called Clair’s parents. They thought I was nuts, but they said I might as well not waste the trip. If I walked there the next day, they’d let me spend one night at their house, and they’d take me to the airport after church on Sunday. And that’s pretty much how it went. Clair’s folks were cordial to me the whole weekend. She and I took some nice walks together on the country roads. We sat out in their backyard until someone said it was late—just like at Helen’s. And that was the real purpose of my trip. I had to experience that kind of conversation again. I’m a sucker for genuine conversation, mostly with women, but guys are okay too. I’m lucky to have a wife I never tire of talking to any time of day or night. As for Clair, it wasn’t love. It was never love. But it was something. Three summers later, Clair was back at Helen’s, studying for her second year nursing exams. I’d just finished my freshman year at Lancaster Bible College. After a tentative start, we picked up right where we left off in Helen’s backyard—talking. We actually went on a date that time, to Shea Stadium to see the Mets. I drove. No need for the subway. Returning after the ballgame, I walked Clair into Helen’s backyard. We talked, as usual. She said my trip to Buffalo three years earlier almost blew it for me with her dad, but she convinced him I was an okay guy. Thanks, Clair. When Helen called her in, Clair walked me along the side of the house toward the car. She grabbed my arm, turned me toward her and kissed me. Then I kissed her, I mean really kissed her. I’d only ever kissed one girl before, and that was just a peck. This was a kiss. And then she pushed me away delicately. “You know,” Clair said, “We’ll probably never see each other again.” She was wrong. Music was life to kids growing up in Brooklyn in the 60s. To describe it will take the next three episodes of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. Next up: Blueberry Hill to Little Deuce Coupe. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I’m a romantic. I believe in Grand Gestures to win the hearts of fair maidens. I cry at some point during every play I see. I’ve seen Wicked in London and Chicago and tear up every time Elphaba rises from the trap door to rejoin Fiero. Unrequited love was my specialty. Harry Chapin wrote the words that fully encompass my early life in the song Paint a Picture of Yourself (Michael). You’re happiest when you’re chasing clouds With a halfway broken heart. It’s easy to maintain a broken heart when you are shy around the opposite sex; heck, when you’re shy around people in general. I could never speak comfortably with the girls in my classes at P.S.114. I was never one to pass little “I like you, do you like me” notes to the cute Italian girl just one seat over. As I got older, I wrote those notes, more sophisticated versions, for my guy friends to pass to their girls. Love poems and the occasional love song flew from my Bic on command, but always for someone else, not me. There was one girl I never had trouble talking to: Judy Phillips, who lived directly across the street from me in an upstairs apartment. Judy could run like the wind, which I admired. She was smart in every subject and skipped a grade in school, making her only one year older than I, but two grades ahead. And she looked a lot like Mary Tyler Moore, which made her totally unattainable. But she was my friend; next to Kurt, my best friend. Judy was a hereditary member of the 93rd Street Gang owing to her brother having been a member a few years earlier. All the guys had crushes on her. Eventually, sometime in high school, she became Billy Walker’s girl. High school romances usually don’t last. Friendships do. I really don’t know how I got to be close friends with the cutest girl in the neighborhood, but I’ll hazard some guesses. First was the fact that Judy, Kurt, and I lived less than 300 feet from one another. Other gang members lived farther away, some more than two blocks. That’s a continent by Brooklyn standards. Second, we all went to Grace Church. While it is true that Judy’s best friend, her “BFF” in this century, was Susan who lived right next door, Susan was Catholic. Sometimes you just couldn’t hang out with them. Maybe they were fasting or something. Besides, telephones were for calling best friends. Kitchen tables, living room floors, and back steps were for hanging out with the guys. Judy, Kurt, and I were “the guys.” I have to admit, I liked best the days when Kurt didn’t show up on the stoop and it was just Judy and me. I wasn’t nervous around her, like I was with other girls. I felt free to talk about the things that really mattered to me because they seemed to matter to her too. Like my stuffed animal collection. They were real to me, and Judy didn’t make fun of me for it, unlike the other gang members. I did admire Judy, though, long after the crush wore off. She was a reader, and so was I. I remember one day when I was over at her house and she was so excited about a story she had just read about Harry Houdini. It was in some kind of kids’ anthology. She let me borrow the book that night. I’d never borrowed a book before except from the Canarsie Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, so Judy was the first non-librarian to lend me a book. For that I will always love her. But the crush ended long ago. I almost had a date with Judy once. Not a romantic date; this was in college and any thoughts of romance with Judy were long gone. We just thought it might be fun since, at the time, we were living only 60 miles apart; she in Philadelphia and I in Lancaster. At the end of each school year, Lancaster Bible College held their Spring Semi-formal. It was like a high school prom (which I never attended, of course) without dancing and with gowns and tuxes not required but almost always worn. My freshman year I was dating no one around the time to be getting a date for the Semi, so I thought it might be fun to visit with an old friend and invited Judy. She readily accepted, also thinking it would be fun to catch up over a fancy country club dinner. As the event neared, I actually was thinking it might be nice to have a real date with Judy, although I truly expected nothing to come if it but laughs. A few weeks before the big night, Judy called me. I knew something was up. She told me she had liked this guy on her campus, John Ward, for some time and had long hoped he would ask her out. Guess what? He did! John invited Judy to her college’s spring fling, and, of course, she said yes. And, of course, the two events were on the same night. When we finished our conversation I felt a little sad. I’d lost my date for the Semi. But I felt a lot happier than sad. Why? Because my friend was happy, and that made it all right. Every once in a while I still talk on the phone with Mrs. Judy Ward. Eventually, I developed another crush, and this led to the worst date and the best reunion ever. I began playing woodwind instruments in fifth grade when P.S.114 offered group music lessons after school one or two days a week. I thought the bassoon with its rich brown color and deep reedy sound would be perfect for me. Like the new recruit with a background in catering is always assigned to the motor pool, I was assigned to the clarinet. I took to the clarinet with surprising ease and soon began private woodwind lessons with a teacher who envisioned for me a stellar career as a musician. I was good, but I was so shy that every solo was an exercise in terror. After two years of clarinet I was ready for a challenge, which came in the form of a tenor saxophone. I picked it up quickly and was soon playing solos in band, orchestra, and jazz ensemble. I didn’t love any of it. I did, however, love Gail, the first chair flutist in band and orchestra. She was the absolute cutest girl I’d ever seen; maybe, and there are those who might debate this, even cuter than Judy. Short, like Judy, Gail had what looked to be the softest, silkiest dark brown hair I’d ever seen. I admired it almost daily from behind her in orchestra and band. I crushed hard on Gail, and, of course, I kept my feelings hidden deep inside me. But there comes a time when even a timid seventh grade boy has to lay his heart on the line. I asked Gail to go on a study date with me to the most romantic place I could think of: the Main Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza. I’m a reader; always have been. I tested off the charts in Language Arts while I was still in fourth grade. To me, all libraries were special, and the legendary Main Branch was the ultimate exotic location. What better place to spend a day with Gail. Wonder of wonders, Gail said yes. Gail said yes! With my impeccable sense of timing, I made the date for the day after Thanksgiving, a day off from school. Oh my God, I’d have Gail all to myself for a whole day. I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it. Like I could never believe I was good enough for those solos in orchestra, I absolutely refused to believe I had anything to offer the cutest girl in seventh grade. When the big day came, I showed up, I went through with it, but I froze just the same. I think Pop took me to pick Gail up at her house. Then he dropped us off at the bus stop for our ride to the library. While waiting for the bus, I thought I’d be debonair and pick up a truly adult piece of literature to read on the trip: The Sporting News, that venerable weekly newspaper covering every American sport in season and out of season. That day I read it cover to cover while Gail waited for me to make conversation. She waited through the bus ride to Grand Army Plaza. She waited for conversation about anything other than our school project while at the library. Then she waited all the way home to Canarsie while I sat reading my paper in silence. In my defense, I was awed by Gail and totally terrified I’d screw up the date. I screwed up the date. Gail and I remained one riser away in band and orchestra right through high school, but we never spoke another word to each other. Until the Internet. Until social media. Until Facebook. Facebook made people do crazy things in the early 2000s. One of those things was allowing a group of fun-loving but not A-list grown-up kids who had known each other at P.S.114 to reacquaint. Slowly, over a period of two years, I reconnected with old friends and acquaintances. I started talking with a couple of them about an upcoming trip to New York to speak at a conference and to visit my brother. Maybe a few of us could get together. Next thing you know, I got a friend request from Gail. I made my trip to New York, had a fun dinner with three other old friends, plus Gail, and we set a date and potential location for a reunion the following spring. Canarsie High never has reunions because with 1,500 kids in a graduating class you hardly knew anyone, let alone wanted to visit with them ten or twenty years later. Undaunted, our little group of event planners booked a restaurant for a champagne brunch. We invited everyone we knew and thought might like to be there. During the intervening months, Gail and I chatted a few times via Facebook Messenger. She told me about her husband, from whom she was separated, and I told her a little about my recent divorce. This time I listened carefully without my head in a newspaper. The big morning came and we gathered at the restaurant. A couple of dozen P.S.114 grads enjoyed reminiscing over Bloody Marys and mimosas. Then the call came that brunch would be served. Gail, who had been visiting with long lost girlfriends across the room, stepped beside me. “May I sit with you?” she said. And finally, face to face, we talked. More about love…or something like it, in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. You can’t grow up in a big city, any big city, without playing in the street. It’s not that playgrounds didn’t exist, it’s just that a) they’re never close enough to actually go to regularly, and b) every story about an abducted kid includes the phrase “last seen headed toward the park.” So into the comparatively safe streets of metropolitan areas go kids after every school day and all summer long. Street games fell into three distinct categories. There were team sports like punchball and touch football; roller skating, where half the fun was sitting on the curb talking with your friends about the latest Top 40 chart; and the running and hiding games like freeze tag, iron tag, hide and seek, and ringolevio. Team sports seem to have produced the most conflict, perhaps because they relied on the highest degree of participant integrity. First, there was the trust issue. On any given summer day, one of us was bound to have a cousin or friend from off the block join us. Every member of the opposing team had to trust the outsider wasn’t a ringer. Second, and most obvious, ball games produced controversies based on split-second bits of action. Was she safe or out? Was the receiver in bounds or did his right big toe catch just a hint of the curb? Since we never had referees or umpires, decisions in such cases were reached by consensus, at best; argument, usually; or fistfight, at worst. Just as every rule has an exception, so did our tradition of never having referees. The glaring exception was the 93rd Street Football Championship, also known as ‘The Day Scott, Sal, and Phil Turned Pro.’ The sports world turned upside down on January 15, 1967 when the National Football League, represented by its venerable champion, the Green Bay Packers, deigned to play the upstart American Football League, in the form of the Kansas City Chiefs, at a neutral site, the Los Angeles Coliseum. The Packers won handily, confirming what was in the mind of most pro football fans, that the AFL was no real competition for the NFL. Joe Namath and his New York Jets would change those minds just two years later. However, the fall of 1967 witnessed Canarsie’s own championship right in the middle of East 93rd Street, when Scott, Sal, and I took on three kids from another block in an officially timed and refereed winner-take-all, pole-to-pole touch football game. We’d never played a game like that before. Our games generally ended only when we got tired of playing, when the score got too lopsided, or when an unwinnable argument ensued after a close play. Timed quarters weren’t part of our routine. Refs weren’t either, but one of our neighbors sensed this was an important competition and offered to observe in order to prevent any game-ending conflict. Having Sal on our team was not necessarily an advantage for Scott and me. He was chunky, clumsy, and slow. Still, he played every game we could think of, even though he was usually the last player chosen. But Scott and I were a well-oiled machine. He knew just how to catch my stubby-fingered spirals, and our Mississippi counting was always perfectly in sync. In spite of Sal, we had this game. Street football games had a unique format, although they featured the two-hand simultaneous touch tackles common to touch football everywhere. The field, however, was the distance between two telephone poles. No lines were drawn on the pavement, so each team received four downs in which to navigate the entire field. If you failed to score in three plays, you were given the choice of “goin’ or throwin’.” Goin’ meant using fourth down for another attempt at the end zone. Throwin’ was the equivalent of a punt. Actual kicking was forbidden due to the chance of a broken window or dented car hood. You got six points for a touchdown. No extra point conversions allowed. Touchdowns had to be definitive or else an argument would end the game. It was a closer contest than we thought it would be. The visitors, whose names I don’t recall, scored first and kept us out of the end zone for an uncomfortably long period of time. Finally, near the end of the first half, the Phil-to-Scott connection kicked in. Our favorite play would have Scott running full speed for three Mississippis, faking a turn toward me, and then running to the end of the nearest car and expecting an almost indefensible pass over the hood or trunk. Two or three of those put us in scoring position. On the next play, Sal snapped the ball and instead of blocking just ran the three steps into the end zone, turned, and caught my pass dead in his chest. Tie score! In the second half we took the lead and, although it wasn’t a rout, our victory was never in jeopardy. When the referee called, “Time,” we led by two touchdowns. The three 93rd Street boys were champions. And then we were more. After the game, our referee/timekeeper/spectator made an announcement to the winning team. “Guys, I’m really impressed with the way you worked together to beat the other team. I want to give you something to celebrate your victory. My wife and I are getting ready to sell a few of our things, and I’d like to give you each something.” He disappeared down the block while we stood around with puzzled faces. A few minutes later he returned with a box of household items and declared that, since I was quarterback, I should get first pick. I looked the box over and then chose a wall clock. It was kind of sixties modern. In later years I’d see that same design in a few other houses across America. Scott and Sal made their choices, and the guy was gone. We looked at each other and grinned. “You know what this means, right,” said Scott. “We’re professional football players,” I replied. “What do you mean?” Sal asked, always a step behind the rest of us. “We played a game and got paid,” Scott explained. “We’re pros.” I said. And I’ve never thought any different. That clock hung on our living room wall, mostly covering an oily stain in the wallpaper, until the day Mom and Pop moved to Pennsylvania. I think it finally died sometime after Sandy and I hung it in our first home. The 93rd Street Gang wasn’t really into sports, but the other kids in the neighborhood made up for their lack of interest. Scott, Sal, and I; sometimes Freddie Lombardo, who lived next door to Sal; and sometimes Robbie Renaldo, from a nearby block; played everything in almost every season. But winters, except for snowball fights and sledding down Suicide Hill next to Grace Church, were for hockey. We didn’t play ice hockey on East 93rd Street, and street hockey with roller skates and a little blue ball wasn’t yet a thing; but we were passionate about “push-pull/twist-twist hockey”: those games with the little hockey players on metal rods. For two years in the late sixties, the living room at 1304 rivaled Madison Square Garden for hockey excitement. Back then the National Hockey League consisted of only six teams, about twenty players each. We reproduced it by choosing teams and memorizing every player in the league. We changed lines and defenses, we called penalties, and we kept stats. Every game featured two players and an announcer/referee. The announcer was a non-playing league member. We were all so good at that, any one of us could have walked right into a radio or TV studio and applied for a play-by-play job. Since there were six teams, but only five players (Scott, Sal, Robbie, my brother, and me), and since I owned the game, I got to play for two teams, the New York Rangers and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Every time I visit a Tim Horton’s coffee shop I can't help thinking, “That guy was one of my defensemen.” Although Scott was a formidable representative of the Montreal Canadiens, and John no slouch with the Boston Bruins, both seasons ended in a playoff between the Rangers and the Maple Leafs. I always chose the Leafs, and the person with the next-best W-L record took over for my Rangers. I think the Leafs won Season One and the Rangers pulled an upset at the end of Season Two. The Baisleys and the Robinses adored hockey, the real life kind we watched on television and in person at minor league Long Island Ducks games in Commack Arena. It was this love that led to one of my most memorable sporting conflicts. It wasn’t a close call on a penalty, though. This would be a conflict between church and skate. It began innocently enough with Scott and I securing tickets to a Saturday afternoon Rangers game. While tickets in the sixties cost considerably less than today, they were still pricey to high school kids. But every once in a while you splurge. We enjoyed the game from our nosebleed seats in what was then the “New” Madison Square Garden, near Pop’s office on Eighth Avenue. Down in Philly there was a new arena too: the Spectrum. Someone must have skimped somewhere in its construction because, after only a few months, part of the arena’s roof blew off in a storm. Philly’s new NHL team, the Flyers, were forced to play their next home game at a different location. They worked out a deal to play that game, against the Oakland Seals, at Madison Square Garden. How does one fill the seats at a sporting event between two expansion teams no one cares about in a venue that is home to neither of those teams? The solution was announced during the second period of Saturday’s Ranger game. Anyone with a ticket to that game, could get into the Sunday Flyers game for free on a first come, first served, basis. Free professional hockey! But there was a catch. The Rangers were playing the Chicago Blackhawks at the Garden on Sunday night. That meant the Flyers game had to be played on Sunday morning. Therein lay the conflict; for me to go with Scott to the hockey game, I’d have to miss church. Missing church was something a Baisley didn’t do. My great-grandfather’s name was on a stained-glass window in the sanctuary. Combined with my parents’ status at Grace, the only way their son was missing Sunday school and morning worship was for illness; and it better be serious illness like chicken pox or measles. I did miss one Sunday one time. That was when I had to go to the bathroom right before the service started, and I was a little late making my way from the men’s room, which was in the Sunday school department, to the sanctuary. Billy Knudsen was hanging back as well. “Let’s skip,” he tempted. I’d never even thought of that before. But it was summer. The choir wasn’t singing, so Mom and Pop would be sitting hand-in-hand toward the front on the right side. The Grace Church members of the 93rd Street Gang always sat in the back, right side. Mom and Pop would never notice if I just weren’t there. I could sneak in at the end while everyone was shaking hands, and who would be the wiser? “You coming?” my tempter implored. “Sure.” And off we went through the Sunday school doors. We were headed for adventure. Adventure found us three blocks away in a vacant lot on the corner of Avenue L and East 91st Street. Vacant lots were rare, but not unheard of in 1960s Canarsie, but one so close to a major shopping area was a bit unusual. Even more unusual was the mustachioed gentleman who stopped Billy and me as we walked by. “You guys wanna make a dollar?” he asked. Remember, this was mid-twentieth century Canarsie, not twenty-first century anywhere. We didn’t feel threatened. Heck, it’s not like we were going to the park. It was just a vacant lot, a little weedy but otherwise bright, cheery, and very public. And a dollar apiece was big money to junior high kids. “Sure!” we both exclaimed. The man asked us to walk through the lot picking up any trash we saw. He said something about wanting to clean it up for a potential buyer. He then handed us a couple of cardboard boxes and we were off. We figured it would take about half an hour, leaving us plenty of time to reappear at the church in time for the end-of-service handshaking. Things went pretty well at first. We picked up some old newspapers, a bunch of candy wrappers, and a few tin cans. Then we hit the macaroni salad. There must have been twenty pounds of the creamy white substance hidden among the weeds. It didn’t smell bad enough to be that old, which was encouraging; but neither of us wanted to pick it up in our bare hands. A stroke of pure luck had us stumble across a bent old serving spoon about then. God was smiling at the little church-skippers. After scooping up the last of the noodles and boxing the remaining trash, with just enough time to race back to Grace Church, we found the lot owner. Hands out, expecting two crisp one dollar bills, we each heard two quarters plop into them. A dollar. Split two ways. Disappointment turned to practicality: one chocolate ice cream soda, one egg cream, and a pack of Juicy Fruit. Per person. Not a bad morning’s work. Billy and I weren’t caught that day, but the guilt kept me from ever wanting to skip church again, until the Flyer game. How could I not go to a free NHL game? What to do, what to do? For once, in a rare instance of not overthinking, I chose to be totally honest with my parents. Okay, I hedged a bit. I told Pop first. Being a hockey fan, he might understand better than Mom, who was only a church fan. The conflict between church and skate came to a head that evening, but it didn’t last long. The overarching principles were clear from the start of negotiations. We were evangelical Christians, descended from Huguenots who fled France in the face of persecution. Christians went to church on Sunday; it was simple as that. But those old Huguenots were Baisleys—Beselles originally—and Baisleys value two things along with their religion: hockey and thrift. By a score of two to one, free hockey beat church. Scott and I went to our hockey game and, during the process, ran into NHL superstars Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita, who were playing in the evening game against the Rangers. I still have the photo of Hull signing my ticket stub from the previous day's game. I’ll always respect my dad’s religion for the tolerance he showed me that day. Maybe he’d learned a bit from his persecuted Huguenot ancestors. I’m a romantic. I believe in Grand Gestures to win the hearts of fair maidens. You’ll hear about some doozies in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed