|

I hated school, didn’t you? When did a day in school ever come close to being as much fun as a day not in school? Don’t get me wrong. I wasn’t a bad student. I was a very good student, well-read, almost as well-mathed, and exceptional at things like sewing and music. I simply didn’t like being told what to do for six hours a day plus a couple hours of godawful homework. I liked learning. I liked the challenge of gaining new skills. I even sort of liked being around other people, at least until they made me want to tuck into a shell like a turtle. It was just that school was the one place my inadequacies were proven every damn day with every damn assignment. During my years as a student, I never used profanity, except in seventh grade. That was the year my brother returned from the Marines. It was also the year I was trying to be like my ninth grade Gangmates. With John’s tutoring, and the Gang's encouragement, I learned to speak the lingua profana. After seventh grade I rarely, if ever, swore, not even under my breath. I felt no need to. My history of foul language can be summed up in words I’ve often told my seminary students: “I never drank until I went to seminary, and I never swore until I became a seminary professor.” But that was now; this is then, and back then I wanted to like school, but school was where I could never be as good as I needed to be for the world that held me in judgment and for myself, who was my toughest judge. Classroom presentations, such as book reports, terrified me. I’d read a book in just a few days. If a teacher would have sat down with me over a Yoo-Hoo and asked me about the book, I’d have gladly discussed it for hours. But to write a book report the way I thought the teacher wanted it, well, that was impossible to my public school self. It would never be as good as it needed to be. I struggled with written assignments all the way through college. Due to my failure to turn in assignments, I got Ds in English Composition and English Grammar, even though the professor recommended me to write for the school newspaper. Let’s face it, I was a paradox. And I knew what that word meant and how to spell it by fourth grade. By seventh grade I was ready for bigger and better things: cheating and general mischief. Tests never bothered me. I had a lot of general knowledge, I read a lot of books of all genres, and I knew intuitively how testing worked. But I was always a little reticent to trust those things. So I began perfecting the art of cheating. I never looked to someone else’s paper for answers to a test. I never outright claimed someone else’s work as my own, except once in fifth grade before I understood the concept of plagiarism. My specialty was the “cheat sheet,” and I created some of the best. The most obvious way to cheat on a test was to write the possible answers on body parts. This worked particularly well for math or science formulas that you just couldn’t remember, or important dates and people for a history exam; but I never stooped so low as to get ink all over myself. I wrote the names, dates, formulas, what have you on small pieces of paper in very fine print. Those papers were custom-designed to fit in inconspicuous places. I wore ties a lot on test days. Cheat sheets fit well in ties, and, if you use a heavier weight paper, they are easily and quickly retracted. I hid cheat sheets everywhere: on the edges of books in my desk, in shirt sleeves and pockets, anywhere they were in my view but not the teacher’s. My all-time favorite hiding place was a stroke of genius. The night before the test, I painstakingly wrote, in minuscule print on a piece of paper about a half-inch by five inches, everything I thought I might need to know. Then I carefully rolled and inserted the paper into the clear chamber of a Bic Stic pen.

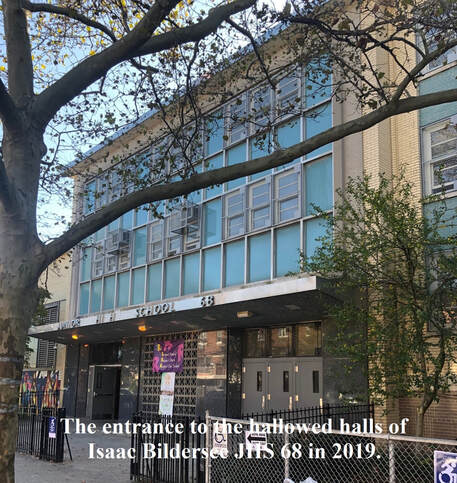

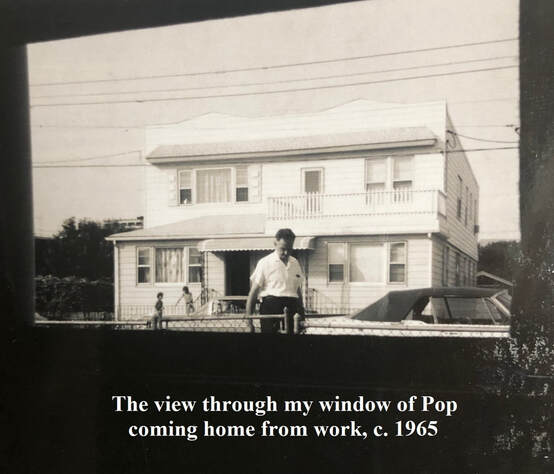

What was the secret? You’ve guessed it by now, I’m sure. The more intricate the means of cheating; the more you learn in the process. All those hours spent writing the information on tiny slips of paper cemented that data in my brain. I never actually used any of the cheat sheets I created, and I doubt any of my disciples did either. I knew they wouldn’t. That’s why I knew they could be entrusted with the secret. Along with cheating, or really not cheating, I was also guilty of some general mischief. I was not—repeat, not—a troublemaker in junior high. If there was a troublemaker at Bildersee J.H.S., it was the school’s namesake. Isaac Bildersee was a Brooklyn school administrator in the first half of the twentieth century. He sparked controversy when, in December 1947, he tried to remove all religious symbolism from Christmas and Hanukkah celebrations in Brooklyn public school classrooms. His plan lasted about two days when the school superintendent put the decision to celebrate religiously in the hands of each school’s principal. At Bildersee J.H.S., I pretty much kept to myself with a few rare exceptions. I only cut school one day in three years, during my last semester. I did it to try and experience what other kids were doing. I was miserable and actually snuck back into Bildersee in the afternoon.  My life at Isaac Bildersee was boring and pretty well regulated by my internal sense of regimentation. For example, I ate the same thing for lunch just about every day during eighth and ninth grade: two salted bagels, from the bagel shop on the corner, and a chocolate milkshake from the Carvel down the street. Every day. Middle initial “C” for clockwork. I went a little crazy in eighth grade though. I think it started when I found out I’d have Mr. Balter for Science a second year. Mr. Balter was a legend at Bildersee even though he was a fairly young man. He cut no one any slack with assignments or homework. His tests came with high expectations, and he didn’t mind failing students in the least. I think I got a B in seventh grade and was struggling a bit in eighth grade. I needed a diversion. Science classrooms in the 1960s had all wooden desks, unlike the modern wood and steel desks in the other classrooms. They were heavy and clunky, and still they were screwed to the floor, to prevent their being stolen by marauding desknappers. Seeing the screws in the floor one particularly boring day gave me an idea. What would happen if… I set to work after school that day. Earlier in the year I had come into possession of an extra copy of the eighth grade English book. I also knew where Pop kept his single-edge razor blades. They were a match made in thirteen-year-old heaven. First, I carefully cut through each page of the English book, a neat rectangle large enough to hold what I needed. Then I realized the pages needed support, so I taped sections of them together, not tightly, just enough to make them stable but still looking booklike when closed. It worked! I filled the hollowed-out book with Pop’s multi-tip screwdriver and a small adjustable wrench. I was ready for Science class. The next day I tucked my alternative English book into my book bag and headed to Bildersee. I sat in one of the back corners of Mr. Balter’s class, with no one behind me, which fit well with my plan. During Balter’s typically thrilling (to him) class, I used my stash of tools to quietly undo every screw and remove every nut, along with some of non-essential supporting bolts. The sturdy wooden desk stood, upheld by gravity alone. When the bell rang, I gently slid my chair out from under the desk. Nothing was disturbed. Nothing looked amiss. As I exited the room, the next class entered. Two of the boys came in already engaged in an altercation. By the time they reached their seats near the back of the classroom, the verbal sparring had escalated into shoving. Out of the corner of my eye I watched the final push. I turned into the hallway and heard the crash of falling plywood. Smiling broadly as I made my way to the next class, I thought I heard Balter scream, “Baisley!” But I may have been mistaken. The next period, from my seat in Algebra II, I watched as two custodians carried the desk, legs folded on top like the arms of a body in repose, down the hallway. Their heads solemnly bowed, the men gave the desk a proper transport to the room in which it would be reconstructed. I beamed. Isaac Bildersee died just six weeks before I was born in 1952. Too bad. I think I might have liked him. Growing up in a religious household has its drawbacks, as you’ll see in The Conflict Between Church and Skate, next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Someone once said, “It takes a village to raise a child.” Hillary Clinton also said it, but she never claimed the maxim as her own. It may be an old African proverb. It has certainly been restated in many different ways over the centuries. Oddly, when Ms. Clinton first said it, a lot of people got their feathers ruffled; something about her denigrating parents, I think. I suspect Clinton’s naysayers have never lived in a village, or ever had to parent someone else’s child, or maybe were never children themselves. I’ve visited the kind of villages in Africa that originate proverbs like the one about raising children. In them, for better or worse, children are community property. They play in public spaces, but many of those spaces are public simply because children play there. Somewhere there exists a title to that space, and it’s in some grown-up’s name; but kids share it as if it belonged only to them, all of them. I grew up in a village. True, it was part of a Zip Code of nearly 100,000 people, which was part of a Borough of four million in a city of eight million. But the extended block on which the Baisleys lived was a village; we kids, the 93rd Street Gang and the other kids who lived there but weren’t lucky enough to be in the Gang, were community property. This sense of community parenting showed itself in small ways and in big ways. Like most city neighborhoods of the 1950s and 60s, kids roamed Canarsie streets freely. The first one out in the morning, at least on Saturdays and in the summer, would run to the next one’s house and see if they were up yet. Typically, on those mornings or late afternoons during the school year, you’d hear the cry, “Can Joey (or Kurt or Judy) come out and play?” Usually they could unless they’d been recently grounded for misbehavior. Play dates were still in their inventor’s mind. Our parents never made appointments for us except for pediatricians and dentists, and those were things we hated. Play was spontaneous, wherever and whenever kids happened to be. Where parents got involved, usually, was once the children settled into someone’s house. Then it was, “My house, my rules.” No one ever had qualms about disciplining someone else’s child for misbehavior. Believe me, we feared other parents way more than we feared our own. For me, community parenting was most effective at mealtimes. True, most times the command from Mom was, “Be home for dinner.” That meant 5:50 p.m., when Pop got home from his office. Sometimes, however, an invitation from a mother, such as Mrs. Robins, superseded Mom’s command. Lucille and Ken Robins were Scott’s parents. Scott was Jewish and, therefore, not part of the Gang. But he lived on the block and he was my friend, at times my best friend. It was with him that I made the daily trek home from Isaac Bildersee JHS every day. You know, the ones that were ten miles uphill. Okay, they were ten and a half blocks, and only the half was a long block, but it was far for a kid. Those walks home seemed longer when you had to go to the bathroom. I always had to go to the bathroom after school. Public school restrooms were for a) smoking, b) dealing in contraband, or c) getting beat up. I avoided them as if my life depended on it, which I believed it did. So Scott and I would walk those blocks as fast as possible, talking all the way to keep our minds off our bladders. Thanks to Mrs. Robins, I had the joy of Jewish mothering. While I was in her home, I followed her rules. No flopping onto furniture. No entering rooms other than the living room, kitchen, or bathroom. And take your shoes off before entering. Never had a problem with Mrs. Robins’ rules, not even the one about eating everything on your plate. I was a picky eater at home, according to Mom. I liked to keep my meat, potatoes, and vegetables separated: meat not touching potatoes and vegetables not touching the plate. I might have suffered through green beans. I especially liked them raw as I’d walk through the grocery store with Mom. She’d always tell the clerk how many I’d eaten so they could estimate the cost of goods devoured. I liked corn, but that’s not really a vegetable, is it? Same thing with tomatoes. Every other green or veggie-like thing was against my principles. Except in Mrs. Robins’ domain. Scott’s mom could get me to eat anything. Broccoli? Yes, ma’am, I like broccoli. Cauliflower? Sure thing! Brussels sprouts? Well, I don’t really like them, but why not? Eventually, mothers talking the way they do, Mom found out what I was eating. My life changed that day. For the few years we lived in Oregon in the late 1990s, my first wife, Sandy, got to be that kind of mother. Though not rigidly at 5:50, most nights we all ate together, she and I and our children, Stephen and Kellyn. That was such an oddity in 90s suburbia that our kids’ friends used to wrangle invitations to dinner just to eat with a whole family. Sometimes we’d play silly games at the table. They’d laugh and laugh and then report back to their parent or parents, who’d stare in disbelief that such relics existed. The Baisleys, the Robinses, the Sullivans, the Bongiovannis, we were all relics. But we ate our vegetables—together. There were exceptions to the rule about Canarsie parents not getting involved in their children’s play. The parents of the 93rd Street Gang were the exceptions. They not only got involved, three or four times each summer our parents actually created memorable events on our behalf. The biggest parent-initiated Gang event remains embedded in my mind even after half a century. I can’t remember any amusement park trip that beats the day Susan’s dad took us to Steeplechase. We needed at least one other driver, so Uncle Nat drove too. (I’m not sure whose uncle he was. Just like Pop being Uncle Artie all over Canarsie, so Nat was everybody’s Uncle Nat.) Steeplechase Park was at Coney Island, but it wasn’t Coney Island. Coney Island was the Boardwalk, the Wonder Wheel, Nathan’s, and salt water taffy. Steeplechase was rides, not a lot of them, but they were super cool because, except for the Parachute Jump and part of the park’s eponymous Steeplechase ride, they were indoors. Not until I visited the Mall of America as a middle-aged man did I again experience such a place. For photos and more information about the history of Steeplechase Park, see this article in Carousel History. https://carouselhistory.com/ny-steeplechase-park-coney-island/ We started the day with the Steeplechase, a horse race ride. Six or eight kids could ride at one time. It was a genuine race. We contorted ourselves into the most aerodynamic postures. We did anything and everything to get the horses, side by side in their predetermined course, to go faster to win the race. I suspect, and maybe always suspected, that each race’s winner was preordained, like some Calvinist lottery. But who cares? Finishing second that day felt like the crowning achievement of my life. Next up was the big Slide that ended in a spiral that gradually spit you out. It was wood, like everything at Steeplechase; smooth, slick, dark brown wood. They gave us burlap bags on which to make the descent. We were warned not to dare let any fleshy part of our body touch the wooden surface on the way down. You could burn off a finger that way. Properly chastised, we slid. Fast. Hot. And in maybe five seconds it was over and each of us, in turn, rolled off our burlap. For a short ride, no one felt cheated. We rode other rides that day. The Himalaya I remember slightly. The Fun House I only recall because Billy Knudsen led us in singing a song with the repeated line, “Sweet marijuana” as we progressed through its various chambers. One of the rides placed you and three others in a low car that sped so quickly on a round course that all the riders ended up pressed into a single human blob. I don’t remember what it was called. During the day, we wandered outside Steeplechase as well. Some of us rode Coney Island’s three great wooden roller coasters, the Thunderbolt, the Tornado, and the awe-inspiring Cyclone. The truly brave souls dared the Parachute Jump that soared above Steeplechase. It pulled you high into the air and then dropped you a ways before yanking your body back up and then letting it down slowly from a dizzying height. I wasn’t one of those souls. No one rode Coney’s famous Wonder Wheel. Perhaps it seemed too tame for the Gang. There was nothing tame about the ride I have replayed in my mind over and over through the years. I know I did it—twice. I just can’t grasp the complexity of its design. That great feat of engineering was the Bobsled. Steeplechase’s Bobsled doesn’t exist anymore, like the park itself, and I’ve never seen another. No twenty-first century insurance company would dare underwrite it. The ride, which consisted of two to four people packed into a bobsled-like car, starts on a track similar to a roller coaster. The track guides the car to an incline and then pulls it upward, again like a traditional roller coaster. Just past the crest of that incline the ride changed from traditional to bizarre. The track ended and the now-free car sped through a twisty-turny course with high semi-tubular walls. The riders, if working together, could create a little extra excitement by leaning into the curves, forcing the car higher up the wall. Next to being stared at by a mother elephant with babies to protect, and no fences to protect me, the Bobsled ride was the most thrilling experience of my life. The Gang piled happily into Mr. Sullivan’s and Uncle Nat’s cars at the end of the day. Although many of the Gang had been to Steeplechase before, and would go again with their parents and younger siblings, nothing could match the fun of that day we spent riding the rides together. Other parents added their unique forms of entertainment to the Gang’s repertoire of experiences. Billy Knudsen’s dad owned a boat. I’m not talking rowboat here; a lot of dad’s or uncles had those. Mr. Knudsen’s was a cabin cruiser with a swimming deck in the stern. We earned our sunburns the day he took us out in the bay. Mom and Pop couldn’t afford a cabin cruiser or a trip to Steeplechase, but what they lacked in quality they more than made up in quantity. During the summer months, a community band gave weekly concerts in the park behind the school administration building in Valley Stream, Long Island. The audience would bring folding lawn chairs and place them on a big macadam square in front of the spacious bandstand. Other spectators spread blankets on the grass around the pavement. Mom and Pop loved what they called The Concert. They made it out to Valley Stream as often as they could, and most of those times they filled the station wagon with members of the 93rd Street Gang. Gang members weren’t really thrilled about the style of music. It was mostly stuff for old people, thirty and up. We did, occasionally, join in the sing-alongs. That was where the band played the kind of songs our parents sang around Grandma’s piano on Saturday nights, things like By the Light of the Silvery Moon with sound effects, and everyone was supposed to sing along. And they did. That’s why the generation raised on the Beatles and the Stones can still sing Let Me Call You Sweetheart. We never sat with Mom and Pop at the Concerts. We’d walk to the outer edge of the park and sit on or by the bridge that crossed a little creek. It was darker there, for making out if you had a significant other. You could hear the music, if you wished to listen, but it was quiet enough for conversation. I loved Tuesday nights in Valley Stream and the laughter and, yes, singing on the trip home: seven kids and two parents. That’s not helicopter parenting, unless the chopper is a Huey that drops you off, let’s you do your job, and returns to get you out of trouble. I appreciated the Gang’s moms and dads for thinking of us without trying to become us or curtailing our kidlike ways. The closest thing to neighborhood parenting I’ve experienced in the past quarter century occurred when the church we were attending in Newberg, Oregon, decided to start its own youth group. This was a big deal because during the five years of its existence, its youth remained part of the founding church’s youth group. By now the church had grown to well over 150 people in each of two Sunday services in its rented building. The kids themselves, most of them anyway, were clamoring for their own group. The pastor, wisely, called a meeting of all interested kids along with their parents. From its very beginning, this group was to be a collaboration between kids and parents. We all learned a lot at that first meeting. For starters, we learned there were too many kids for just one group. We also learned that high school kids have different needs and expectations than middle school kids. We made a decision to meet again soon in two groups, but that both youth group design teams would include kids and parents. My son, Stephen, was a founding member of the senior high group, and I was a founding parent. Once the group got going, the kids generally planned the meetings and chose the events. We parents were there for support and occasional guidance, but not to run the show. Still, the kids liked having us around. I enjoyed the friendships forged with church members I hadn’t met before. The two youth groups were so successful that within a few months the church hired a youth pastor to oversee them. He did not run the senior high group; the kids did. His daughter was in the group, but when he showed up it was as her father, not as the boss. A lot of trust developed in those teenagers; trust in each other and trust in their parents and the other parents. We had a lot of fun doing things together, like our improv nights based on the Whose Line Is It, Anyway comedy show popular on TV. In the more serious moments, the high school kids felt free to ask real questions about faith and life. The group even founded a puppet ministry for the church’s children, complete with puppeteers, musicians, and sound and light techs, all under eighteen. As they neared the end of Stephen’s final year with the group, I learned that neighborhood parenting was still alive and well if we allow it to be. One spring evening before graduation, the high school kids met in one of their homes. It was the night where they would celebrate the five group members who were graduating. At one point in the meeting, each graduate was asked to take a seat in the middle of a circle of all the kids and whichever parents were there. Each graduate was to share their dreams, hopes, and concerns for their immediate future, and the group would listen, giving words of affirmation and support. Stephen’s turn in the center arrived, and he sat in the chair. Then he spoke to directly to me. “Dad, I’m going to say some things that you don’t know about. Mom knows, but you don’t. So I’d like you to leave the room. I’ll tell you eventually, just not tonight. Okay?” What was he going to say? How did Sandy know it and not me? I thought I knew my son, and he’d been keeping secrets? How dare he tell other kids’ parents and not want to tell me? How dare he ask me to leave the room? But he did. And I did. Sometimes your best parenting is done by someone else’s parents. I hear it takes a village. I hated school; I’ll admit it. I’ll also admit I had some fun in the hallowed halls of P.S.114, Isaac Bildersee Junior High and Canarsie High School. You’ll read/hear about it in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I dearly loved the kids I spent most of my early life with: the 93rd Street Gang. We were not your typical New York City street gang except in a few very select ways. We always left the block in a group. Even though on only one occasion do I recall ever being threatened by a group outside our neighborhood, and that was just hyped-up bluster, we preferred not to leave the hallowed macadam and concrete of East 93rd Street, between Flatlands Avenue and Avenue L. And we really only hung out between Avenues J and K. In other words, we lived on stoops belonging to the Kriegels, the Phillipses, the Sullivans, and, rarely due to Isaac, in my backyard. That backyard part changed dramatically after Pop built his screened-in patio. I always looked up to my dad as an athlete and a man of faith, but I never really saw him as a carpenter until he got the idea to use the east wall of an old shed to create an elaborate lean-to that featured three sides made of wood-framed storm windows in the winter and wood-framed screens in the summer. It was a work of genius. I never knew from where Pop got the idea for the screened-in patio, maybe from a magazine. I suspect the plans were drawn by one of Pop’s three engineer brothers-in-law. But Pop built it, with very little outside help. It was a true work of art, as well as a work of Art. The roof was sturdy enough to hold three or four kids playing on it. The windows were secure enough to withstand a couple of serious hurricanes. The patio even extended enough past the old shed to allow a storage area to be built that provided an off-season home to the screens and windows. Genius. More than all those things, the screened-in patio gave the Gang a refuge from the weather when it was inclement and from Isaac all the time. The patio was enjoyed on summer nights by the Gang, on Sunday afternoons by family and Mom and Pop’s friends, and on Sunday nights after church by the kids from Grace. We held our “carouses” there when we weren’t carousing at the parsonage. Being denied almost every worldly pleasure our non-Grace friends enjoyed, the one thing we got was an after-church gathering—a carouse—about once a month, where we could really just be normal kids. Okay, we couldn’t swear, and at the parsonage we couldn’t even listen to Top 40 music. But the silly icebreakers, the serious talks, and the snacks were worth it. Add the Beatles and the Stones to the mix, at least in the screened-in patio, and it was almost heaven for kids who thought heaven was only for them. No, we were not your everyday street gang. Add the Catholics to us Grace kids and we were something else, but something good. So we never left our friendly confines except as a group. And we would stand up for each other against any outsiders, no matter how hard we fought among ourselves. Those are gang-like things, right? There were some less-than-gang-related activities, however. Somehow, Billy Knudsen got hold of a Super 8 movie camera and the Gang became filmmakers.

The Soupy Sales Show was hip enough to attract guests like Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland. It featured pies in the face—Soupy’s trademark—as well as sketches kids laughed at but only grown-ups understood. The Gang loved Soupy, none more than me. I bought every piece of Soupy Sales merchandise I could get my parents to spring for. I had a big Soupy button I wore to church proudly. But the piéce de résistance was my oversized “official” Soupy bow tie, bright red with white polka dots. I actually wore it to school one time, but the teachers made me take it off: too distracting. Not too long ago, I think I saw it in a box somewhere. I’ll have to look again. As much as I loved Soupy Sales, he and his show provided me with two of the greatest disappointments of my young life. The first was all on Soupy himself. The second I’m sure he had little to do with. One year, during the successful run of his New York television show, Soupy was forced by the network to work on New Year’s Day. He was not happy, so he decided to do something outlandish, but not intentionally bad, on his show that day. Because Soupy regularly broke down the “fourth wall,” he spoke directly to his viewers; that is, the predominantly little kids who tuned in every day, even on New Year’s. Soupy simply instructed his young fans to go into their parents’ bedrooms (assuming they were sleeping off New Year's Eve), remove the green, wrinkly papers from their purses and wallets, and send them to him at the address shown on their TV screens. He really didn’t mean it seriously, or so we who believed in him believed. Soupy may not have taken himself seriously, but his little fans certainly did. Within days the network was deluged with hand-printed envelopes containing cash. Soupy announced on air that all monies received would be donated directly to charity. A very embarrassed WNEW wanted to suspend Soupy, but a groundswell of fan support—presumably his young adult and teen fan base—held the network in check. I was in-between, maybe 13 or 14. I knew Soupy was kidding, and it didn’t bother me at first. Then I heard about little kids, who trusted their idol, stealing money from their parents’ rooms. It didn't feel right. He should’ve known better. I didn’t know then why he did it. Maybe it would have mattered. I don’t know. I was just disappointed in my pie-faced Soupy. If idols are false gods, that would have made Soupy Sales my false god. But the Real (if you’re so inclined to believe) One bestowed on me an even greater disappointment that year. Have you ever wanted something so strongly you started to believe you deserved it? And then the more you wanted it you almost felt it was already yours? That’s how I felt about the full-scale rideable replica of a nineteenth century high-wheel bicycle that was first prize in a contest held by one of Soupy’s sponsors. All I had to do was enter, or write a short essay, which would have made me even more confident, aspiring reporter that I was. I sent in the requisite box top, index card, essay, whatever and, like Ralphie in A Christmas Story, waited for my prize. I dreamed about that bike. I truly expected to win that contest. Why? Because I had prayed about it. I prayed about it every day before, during, and after The Soupy Sales Show. I imagined myself seated over that giant front wheel high above the kids with their 26” Raleighs and Schwinns. I knew the bicycle was mine. The contest ended. I waited to receive news of when the high-wheel was coming, or at least a congratulatory letter telling me where to pick it up. Nothing. It was God’s fault. Dammit! I’d prayed as hard as anyone ever prayed for anything. Okay, maybe not as hard as Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, but God didn’t answer his prayer either. Something died in me the day I realized the high-wheeled bicycle wasn’t coming. No, I didn’t lose my faith, but I was severely disappointed in a God I thought would do anything for me. You might call that being dis-illusioned; that is, having my illusions about God removed. To a thirteen year-old it just plain sucked. After Soupy Sales there was Batman, who was big everywhere. The 93rd Street Gang had to capitalize on that, and this time we had a plan. Setting up our Batman movie took days, maybe even a week. We had starring roles to cast, which went to Eddie Gentile (Batman) and Billy Knudsen (Robin). Our movie would include all the male villains from the TV show that we could think of: the Joker, the Riddler, the Penguin, even a one-episode minor bad guy called False Face, who always wore a mask and a black turtleneck with his trademark FF on the chest. We needed the lowest rung on the Gang’s ladder for that role: me. Still, there must have been an unspoken lower rung. In spite of Cat Woman’s popularity on TV, and with two talented female Gang members available—Judy and Susan—we stuck with an all-male cast. Casting cameo roles, so vital to our movie, took a bit of inspiration. We needed someone older, but not ancient, to play Commissioner Gordon. Since my brother was still living at home, he seemed the perfect choice. His military bearing gave him the right look for a street-wise career cop. Since I had the only house and yard big enough to pass for the Wayne mansion, the role of Alfred fell to Pop. With utmost dignity he followed the script to the letter and brought Bruce Wayne the batphone when the call came from the commissioner. Pop was an awesome Alfred: so dignified, so proper, with a little twinkle in his eye. The plot, as in all our films, was tentative. Still, the plan called for a bank robbery, a police chase, and a major fight scene. It could never happen today. But in 1966, the necessary events actually transpired, with a little luck. First, we needed a bank robbery. Well, Canarsie had a lot of banks, but which one would allow a half dozen teenagers with a camera to film a robbery? The first one we asked, it turns out. Try that in the 21st century. We were given permission to film the bad guys entering the bank in costume and then leaving the bank with bags of loot, which we provided. No customers were in any way put out by the filming. Second, we needed a police chase. We planned to ask or beg a police officer to chase us on foot, but as we stood around the bank setting up the shoot, two NYPD vehicles happened to pass by. Our camera operator was johnny-on-the-spot and captured the whole scene, which was spliced into the film to make it look like the cops were chasing us. It was perfect. The scenes where Commissioner Gordon called Batman and where Alfred delivered the batphone went off perfectly. Our remaining challenge was getting the superheroes into Police Headquarters. It only took a little persuasion from our cameraman, the only one of us not dressed in a ridiculous costume. He simply walked up to the Desk Sergeant of our local police precinct, explained what we were doing, and received permission to film Batman and Robin running into and out of the police station. It was as easy as robbing a bank. The battle royale between the heroes and villains took place in the dunes of Seaview Park by Jamaica Bay. Some films are known for their elaborately choreographed fight scenes, such as those in John Wayne movies like McLintock. Ours was just an excuse to roll around in the sand. Barely waiting for a stage punch, we dove into the dunes; we rolled down them, somersaulted down them, and sometimes fell down them for no apparent reason. Eventually, all us villains were incapacitated and justice prevailed. Today, our effort would have been posted to YouTube, and maybe someone would notice and next thing you know we’d be pseudo celebrities. In 1966, when the movie premiered in Eddie’s basement, and then went on the road to a few more basements and dens, we were genuine celebrities, stars of the highest magnitude, at least on the block. At least in the neighborhood. And that’s where it really counted. Someone once said, “It takes a village to raise a child.” That is no less true in Brooklyn than in Zimbabwe. Read about neighborhood parenting in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Warning: adult themes and content. The other day, Jen asked me about the first time I ‘did it.’ There is something intrinsically sexual in that question. No one, when watching a plumber replace a section of pipe, says, “so, when was the first time you did it?” in reference to the plumbing project at hand. No student, while watching me teach, ever asked me, “when did you first do it” expecting a story about my initial appearance in front of a class. When people speak of ‘doing it’ for the first time, it is always sex. And why not? We are curious about sex from the moment we first realize there are parts to our bodies. Babies touch those parts on themselves. Little children show those parts to their friends, and ask to see theirs, out of curiosity. With the same sense of wonder those children terrify mom or dad (oh, please let it be mom) with the question, “Where did I come from?” Peoria will seldom suffice for an answer. In every species of animal, I suspect, curiosity about sex comes with being alive. When Jen asked when I first ‘did it,’ I steeled myself against revealing the one thing I had never told anyone; not her, not my ex, not even my brother—no one. Even as I write this I wonder how I will share it with my readers, mostly family, and my editor, an almost total stranger. Answering Jen’s question in person was somewhat cathartic; I’m not sure how it will work out in writing. Here goes. My mother never uttered those terrible words, “You’ll go blind.” Ever. Fact is, neither Mom nor Pop ever initiated the traditional adolescent conversation about the proverbial birds and bees. I do, however, recall a time when I was about twelve that my father came into my room as I was putting on my pajamas. Very apologetically he asked if he could examine my... He didn’t finish the sentence, just pointed “down there.” I acquiesced, he looked, and then he pronounced me “normal.” I was glad to hear that, although I wasn’t quite sure what “normal” signified. Some weeks later, I felt anything but normal. I awoke feeling really weird and pulled my pajama pants down to reveal a penis the color of an uncooked shrimp; you know, translucent and veiny. I was terrified. What was happening? Was it going to fall off? I was also too mortified to tell anyone, especially Pop, who had so recently declared me normal. But, even in this most uncomfortable situation, turns out I was normal. Hindsight and a cooler head lead me to believe I had merely observed my first personal erection. I processed normally into puberty, not really identifying the condition with my own body but experiencing its joys and challenges vicariously through the older guys in the 93rd Street Gang. They were my instructors, my mentors, and my heroes. Through the two Billies plus Jerry and Toody and Kurt, I received top-notch sex education. I learned about the basepaths of sex, first through home. However, the church taught me to take every pitch, hoping, at best, for a walk. I learned names and nicknames and euphemisms for every body part remotely related to procreation or pleasure. I got them confused and really didn’t learn even the basics until I read a great little how-to book in Bible college, called, deceptively, Sex Is Not Sinful?. In his vain attempt to keep me from having premarital relations, the author armed me with all I needed to be dangerous. Wait! I don’t want to reach the climax of this chapter too soon. Let’s backtrack. One aspect of my education began long before college. It was unexpected, pleasurable, and, of course, completely normal (although I didn’t know it at the time), which brings me to the Sunday New York Times. We had a full weekly subscription to the New York Daily News, the wonderful rag that bordered on tabloid but contained enough hard news and erudite commentary to be a legitimate news source. Pop took the Sunday New York Times because he loved a challenge, and the greatest challenge he could think of was the legendary New York Times Sunday Double Crostic, his favorite puzzle. I cared only about the comics, of which the News had a dozen pages and the Times had none. Up until I was thirteen, I felt cheated by the Times because of that. What was the point of a ten-pound newspaper if it didn’t have Terry and the Pirates or Blondie? Somewhere in my fourteenth year I discovered the value of the Sunday Times. In lieu of comics, the Sunday Times had a most impressive magazine; a colorful section of local news and ads filled with photographs: the rotogravure. I suppose it contained well-written prose, though perhaps not as well-written as that within the Book Review section—another whole magazine—but, like any pubescent boy stumbling upon a Playboy magazine, the prose was not the main attraction. For me it was the fashion ads. New York fashion ads in the 1960s were filled with the latest creations by Pierre Cardin, Mary Quant, and my personal favorite, André Courrèges. And the models who wore them in the photos wore them perfectly. My God those models were beautiful. They were all the inspiration I needed to do it for that historic “first time.” One Sunday morning, I was sitting in the living room perusing the Times magazine while waiting for Mom and Pop to get ready so we could all walk to Grace Church. I was fully dressed for the service. It must have been winter because I was wearing corduroy pants in a kind of green khaki color. They were ugly and way too loose-fitting. Funny the things you remember. I had been admiring the models in the ads from afar when I turned the page and was stopped cold by the cutest little black dress and its inhabitant. I can’t ever recall seeing someone so absolutely stunning. With no other recourse available, I took matters into my own hand. Corduroys on, I touched a part of me that was suddenly larger and firmer than it had been a minute ago. Then I slid it eastward just a bit. Then westward. Yes, I remember. The chair was red and it faced north. Within seconds the woman in the little black dress had transported me into a bliss I had never known. Eastward, westward a few more times and I could hold it in no longer—literally. Something for which I had neither name nor explanation gushed from deep within me and smack into the corduroys. At first I thought I’d peed myself. Then I realized there would have been a spreading stain if I had. No, this felt different. I repaired to the bathroom to assess the damage. We never went to another room in my house; we always repaired to them for some reason. So I repaired to the bath. There I discovered a gel-like substance clinging to the front of the crotch inside my pants. It cleaned up with remarkable ease, but the water I used to get out the small stain was going to take a few minutes to dry. I prayed my parents would be late for Sunday school as usual. They were. Now I had to live with my secret. I didn’t live with the secret for long. That is, I kept it as a secret for a long time, but I didn’t live too long before I “did it” again. It was probably the following Sunday, but I was better prepared. This time I waited until afternoon for what I hoped would happen to happen. And I took precautions. I excused myself from watching whatever sporting event was being televised, which separated me from Pop’s potential discovery. Mom was always busy with something on Sunday afternoons, so I excused myself from her as well. Then, with the comics and magazine from the Daily News, and the rotogravure from the Times, under my arm, I repaired to the upstairs bedroom to “read” for a while. I got a lot of reading done on Sunday afternoons for the next couple of years. Funny thing was, the upstairs room, the only room up there not part of Isaac’s domain, was Mom and Pop’s bedroom. They never let on what I’m sure they knew after a few weeks. And they never found the stash of fashion ads that was growing under their wardrobe. Or maybe they did and didn’t know how to confront me, figuring it was only normal. Eventually, my secret came out in a most embarrassing manner, and yet tempered by Pop’s gentle ways. One afternoon I was lying on the bed in my room—ground floor, front of the house. I might have been reading From Russia with Love, having recently discovered Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels. They were incredibly stimulating even without pictures. I got so worked up by the vivid sexual images—the Fleming phrase “long, slow love in a narrow berth” still gives me tingles—that I forgot my location. I didn’t even hear Pop open the gate and walk past my window. A little while later, Pop called me for dinner. He sat on the edge of my bed and very matter-of-factly said, “I saw you in the window a few minutes ago. There’s nothing wrong with what you were doing, but if I could see you, then somebody else might. Keep the shades down in the future, please.” And that was that. In one short paragraph Pop dismantled the entire fundamentalist anti-masturbation narrative and saved me future embarrassment. He was my new hero. Of course, we all have that other first time. Guys generally make it up. We don’t all run around like feral cats making meaningless conquest after meaningless conquest. Okay, most don’t, and the rest lie about it. But there’s always a first time. I didn’t date much, hardly at all in high school. I was cadaverously skinny, unshakably self-defined ugly, and painfully shy. I had crushes I wouldn’t dare talk to, and lovers so secret they never knew. Then I hit Bible college. Bible colleges exist to bring couples together by forcing them apart. You’d think folks who take the forbidden fruit story literally would learn a lesson from it. Nope. They continually forbid, or severely restrict, dating, while simultaneously telling 18-22 year-olds they need to find God’s one perfect choice for a mate. It’s a recipe for broken hearts, unsafe sex, lightning—if not shotgun—weddings, and bewildering divorces. Been there. Done that. Later chapter. But there’s always a first time. Yes, I was in college, but I had been in an on-again off-again relationship since my junior year in high school. I lived in Pennsylvania. She lived far away in another state. The whole thing was doomed from the start, and it was beautiful. Meanwhile, after seeing each other occasionally and writing a lot of real snail mail letters, we spent a few days together at my parents’ house. The first night there we went out for hot fudge sundaes. They were like foreplay for her. I’ll never understand that, but it was also beautiful. What happened when we got home was somewhat less than beautiful. With runners at all the bases we—I think it was we; she seemed to know what she was doing, I sure didn’t—tried for a grand slam. And like a walk-off home run, it was quick and it ended the game. Okay, the game went on a couple more innings, but it only got a little better. Then it was over. She went home. We never wrote again. We both married other people. Harry Chapin wrote a song called Manhood just four years after that week at Mom and Pop’s home in Pennsylvania. One line sums up my first, second, and third times: Manhood means that you should Get someone else Beside yourself Feeling good I hope somewhere along the way I took that to heart. There’s always a first time. Who’s your favorite Batman? Christian Bale? Ben Affleck? Michael Keaton? Adam West? Mine is Eddie Gentile. You’ll see why in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed