|

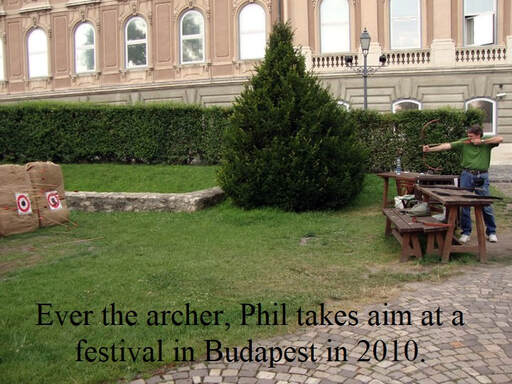

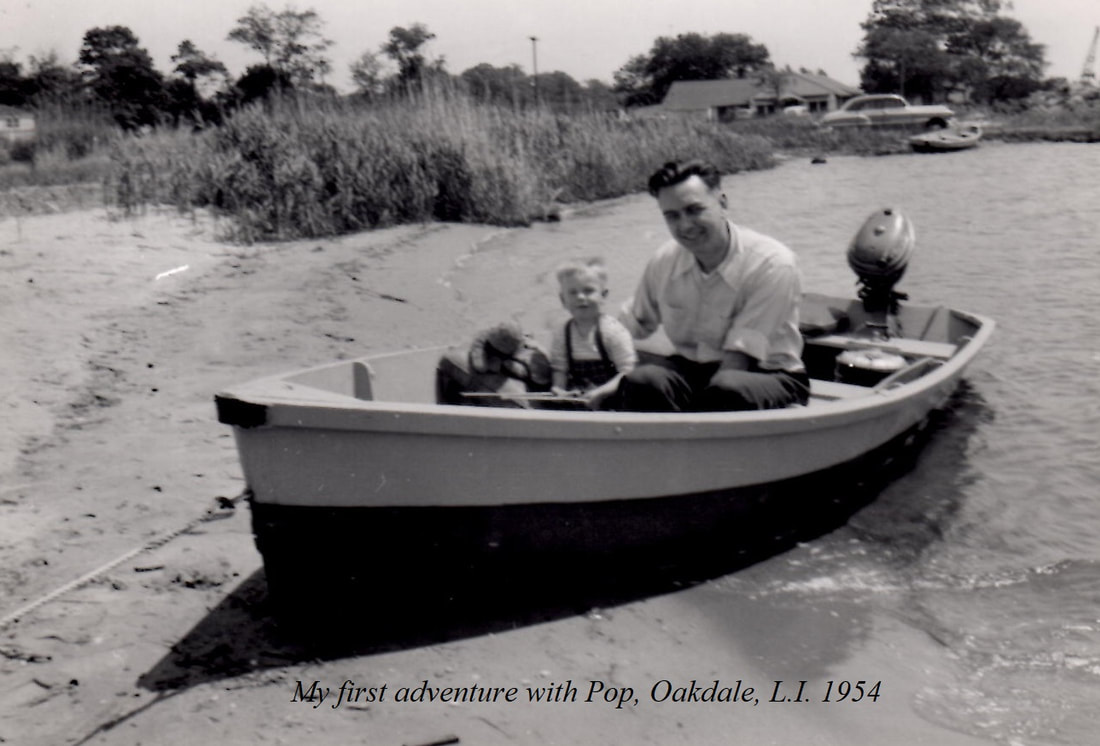

An important rite of passage for American children is their first time away from home without their parents. Maybe it’s a weekend with the grandparents. Maybe it’s a three-day trip to a Disney park as a guest of their best friend’s family. My first trip away from home by myself mirrored that of many of my neighbors: summer camp. Everyone went there, boys, girls, everyone; and they seemed to enjoy it. I’d hear my friends talk about swimming and boating and campfires at some exotic Catskills location, and, of course, I wanted to try it. My opportunity finally came in the form of the Christian Service Brigade. Christian Service Brigade was the fundamentalist Christian’s Boy Scouts. We learned things en route to rewards, kind of like merit badges. Along with tying knots, those things included Bible verses and basic doctrines of the Church. We played games in Grace Church’s fellowship hall during the winter, and we did outdoorsy things in the spring and fall. Like Boy Scouts with their Cub Scouts, Brigade had its younger version, the Stockade. Stockade was for kids twelve and under. I was part of the “under.” My late year birthday kept me in Stockade even when other kids in my school grade were promoted to Brigade. This kept alive my jealousy of the Brigade guys longer than most of my fellow Stockaders. We had every right to be jealous of the Brigadiers; they did the fun stuff. Our games were tame, like kickball; theirs were wild, uninhibited, like dog piling, where everyone jumps on top of one kid and a splendid time is had by all. Indelibly etched into my brain is the winter night I felt the most childish, the farthest separated from the Brigadiers, who included some of my own 93rd Street Gang members. We Stockaders were in the balcony of the fellowship hall, probably having a Bible study. All of a sudden a commotion sent sounds of unparalleled excitement from the floor below. Before we had a chance to crowd the railing to see what had happened, an adult leader rushed in to shepherd us out of the balcony. Blinded by our confinement in a little lobby, we could only imagine the thrill of what was happening beyond the double doors. Soon the details began filtering out to us. It was more awesome than we’d imagined. Big Nick had broken his arm. This was too much. Can you imagine what kind of fun the Brigadiers must have been having for Big Nick to break an arm? We never had that kind of fun in Stockade. Jealousy ruled the Stockade that night and for weeks afterward. During my year in Stockade we heard a lot about Brigade Camp. It sounded like a cross between those Catskills camps my friends went to every summer and Marine boot camp. I begged my parents to send me once I found out that Billy Knudsen was going too; and, although he was ahead of me in school, he was close to my age chronologically, and he was still in Stockade like me. I’d be in camp with my hero from the 93rd Street Gang. Oh happy day! The week of Brigade Camp finally arrived, and Mom and Pop drove me there. It was somewhere Upstate, probably the Protestant side of the Catskills. Billy and his parents arrived about the same time, and together we went to register. That’s when things started to unravel. By virtue of his being older than I, Billy ended up in a different cabin. My one link to East 93rd Street—home—was broken. I was on my own among seven strangers, one of whom was our counselor, who was indeed stranger than most. He had this perpetually faraway look in his eyes. By midweek, rumors were flying about his use of chemical additives. None proved to be factual, but that hardly mattered to us campers. Mom and Pop had warned me about homesickness, so I anticipated a certain longing for my own bed and my stuffed animals. (Stockaders weren't expected to need stuffed animals.) What they didn’t warn me about was having to pee in the middle of a cold, dark Upstate night. And that first night I had the urge. The thought of venturing into the black void between my cabin and the toilet/shower complex terrified me. Least of all were the skunks and bears I might encounter on the way. My greatest fear was that I might meet another boy on the way to relieve himself. I had a kind of performance anxiety about peeing in public. If I had to pee next to another kid, well, I might as well wait until morning. That night I did. The next night I could not hold it in no matter how hard I tried. I slipped quietly out of my bunk, secured a pair of flip-flops to my feet, and opened the cabin door to a frigid Upstate night. The distance from my cabin to the shower/toilet house was maybe 50 yards. It seemed like a mile. Every step brought a new sound: the chirp of a cricket, the patter of rodent feet, the whoosh of a breeze through tree branches. My nose hairs stood on end anticipating the dreaded scent of a skunk. Just short of an eternity later I reached the toilet. Praise the Lord, no other campers were there. Oh my God! No other campers were there! I stood alone at the urinal. I had to go, but to do so meant making myself totally vulnerable for at least a minute. If a bear stuck his head in the door, I couldn’t run. If another boy entered the building, I would be completely out in the open. Every second burned with agony. Finally I finished and made my way back to the cabin. My warm sleeping bag felt so good after the cold night air: the cold night air that was already making me need to pee again. Nights at camp were horrible. Days at camp weren’t much better. Day One started out with great promise. After a breakfast of cereal and milk—eggs might have been on the menu, but I didn’t eat eggs at the time—the Activities Director helped us sort ourselves into interest groups for our major week-long skill building activity. Since some of the choices included boating (swimming proficiency, which I lacked, required) and air riflery (Mom made me promise not to try it), I opted for horsemanship. I loved horses. As a backup I picked something a short, skinny, non-swimmer could do, or so I thought: archery. I got my second choice. What could be more equal to my experience than archery? I’d watched Errol Flynn in Robin Hood six times in one week on the Million Dollar Movie on WOR-TV. I loved the television series, Ivanhoe. And every time I heard the story of Custer at the Little Bighorn, I couldn’t help but admire the skill of the Sioux warriors. Yep, it would be archery for me. I learned a lot that week. At our first session with the archery instructors I learned a new song. Each of the skill building groups had a theme song. Ours, sung to The Caissons Go Rolling Along, was The Archers of Good Ol’ BC. BC referred to Brigade Camp not some prehistoric ancestors. I memorized the song overnight because they told us there’d be a test the next day. There wasn’t. There was, however, more to learn: bow and arrow safety. If you had asked me, prior to my joining the Archers of good ol’ BC, what bow and arrow safety was all about, I would have naively responded that one should not point a loaded bow at someone. At Brigade Camp I learned about the safety equipment we were issued. First, I had to slide some kind of leather band up the arm that held the bow. This was to protect my arm from the arrow passing by and from getting thwacked by the bow. Then I had to put a little leather Band-Aid-like device on my string hand fingers to protect them from something. After a few practice attempts at putting on the safety equipment, I was ready to load and aim my first arrow. But that would come tomorrow. Wednesday activity time arrived—finally—and we, the Archers of good ol’ BC, were ready to shoot. The targets seemed close enough for our amateur status, although we were sure we could hit them from much farther away. I joined the line that stretched opposite a row of concentric circle bullseyes, donned my safety gear, received the long-awaited bow and quiver of arrows from the counselor, and prepared to fire. That’s when I realized I was not as suited for archery as I’d imagined. Pulling back the string, with an arrow on the bow, required a lot more strength than my skinny arms were used to mustering. I tried my best, grunting a little, until the string was as far back as I could get it. Then I released the arrow. About halfway to the target it dropped to the ground. My learning curve that day included the concept of trajectory. Lacking the arm strength to pull the string tighter, I had to find an alternate route to the target. The counselor suggested I aim higher and let gravity do the rest. With renewed confidence I set arrow to bow and tried again. This time the arrow hit the ground only a few feet short of the target. Gravity worked, but a little too well. Determination drove me to one more attempt before the end of activity time that day. This time I would use my new friend, trajectory, to its fullest potential. I aimed high, and yet I kept one eye on the bullseye. Summoning strength I didn’t know I had, I pulled back the string and then let go. Thwack! The string cracked in my ear, and the arrow was on its way. A second later its silver tip struck, bullseye! Then it bounced harmlessly to the ground. My best, my absolute best shot still did not possess the velocity to pierce the target, but at least I knew I’d hit dead center. My archery improved slightly during the remaining two days of Brigade Camp, and that part became my favorite time of the day. Meals weren’t too bad either. I liked the way we called the watered down Kool-Aid, “bug juice.” Still, terror lurked in two locations on the camp’s acreage: the playground and the lake. You'll read more about the playground and the lake in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I wasn’t raised color blind. I knew there were people with different skin tones. Okay, I was pasty white. Everybody had a different skin tone than I. But I knew that black people lived in the Projects down by Jamaica Bay. White folks lived there too, I was recently surprised to learn, including the man who one day would be CEO of Starbucks. I did know one black family who lived in a predominantly Jewish part of Canarsie. For a year in junior high their son and I palled around, hanging out in one another’s homes. I think his parents had moved there from Jamaica or someplace. The 93rd Street Gang were as racist as anyone else in the 60s, and the names we called each other—names we’d never use today—reflected that. If you were black… well, we’d have used a word beginning with N. If you were Puerto Rican you were a spic. Toody Marciano and Jerry Lombardi were wops. One day, gang members Billy Walker (mom from Puerto Rico), Susan Sullivan (Irish), and Toody were walking side by side ahead of the rest of us. Soon those in the rear, me included, started chanting, “Spicmickwop” over and over. Kids are cruel, but we loved each other. We didn’t really know many black kids. The Alcantaras were dark-skinned, but they were Puerto Rican, like Billy Walker. If a black family had moved into the new houses put up in the vacant lot next door to my house, instead of the Romanos (wops), and had kids our age, they’d have probably gotten into the gang just like Mary Romano did. The biggest difference I saw between blacks and whites in Canarsie was economic. Blacks lived in the Projects. The apartments were smaller than the half-houses my friends lived in. It wasn’t the ghetto Elvis sang about, the Projects, but it wasn’t like my neighborhood either. In the winter of 1961 I learned there were worse places to be black than Canarsie. John graduated from Brooklyn Tech in 1960. After three days as a chemical engineering major at City College of New York, he left academia for good and joined the U.S. Marines, heading to Parris Island, South Carolina for boot camp. Boot camp was everything one might expect. Not long ago, when prepping for a role in the play, A Few Good Men, I asked John what boot camp was like in the Marines. He said, “Did you ever see the movie Full Metal Jacket? That’s what it was like.” Mom, Pop, their friends Madelyn and Mervin, and I went to South Carolina for John’s graduation. Road trips always meant a crowd for my family. I guess if a car wasn’t full it wasn’t worth wasting the gas. After Parris Island we headed for Daytona Beach, Florida. Before long we were in the Deep South. In 1961. Somewhere on US 501 I had to go to the bathroom, probably when Pop stopped for gas, maybe sooner. We pulled into a gas station, and I jumped out of the 1960 Ford Fairlane. I ran to pee and stopped cold. Before me stood the doors to two men’s rooms: one was pristine, white, shiny; the other had peeling paint over rotting gray wood. Mine, at least I hoped it was mine, said MEN. The other said COLORED. Weird, I thought. After ridding myself of the last bit of fluid, I needed to replenish. I looked for a water fountain and found two. Again, the clean porcelain of one—unmarked—contrasted with the brown and green stained bowl of the other, marked COLORED. Enjoying my privilege, I drank from the nice one. That night, in a motel with a Magic Fingers vibrating bed (25 cents), I asked Pop about the water fountains. I’d like to say he told me how wrong they, and the bathrooms, were; but I just can’t remember. I know they bothered him. I also suspect they didn’t surprise him. I’m sure he knew life was like that only 600 miles from Canarsie. Was it like that in Canarsie? I don’t remember, which may mean it was. But maybe there was hope, at least in little bits. All the kids at Grace Church called Pop “Uncle Artie.” It wasn’t that special. “Uncle” and “Aunt” were terms of respect used by children of all their elders at Grace. I remember one Saturday when Mom and Pop and I were shopping at the Bohack supermarket on Avenue K, about where what used to be Canarsie High School sits now. We neared the checkout when a little black kid came running full tilt down the produce aisle. It was Curtis, whose family occasionally attended Grace Church. “Uncle Artie! Uncle Artie,” Curtis joyously shouted for all to hear as he jumped full body into my father’s arms. White folks’ eyes fastened on Pop from all over the store. Pop didn’t put Curtis on the sawdust-lined floor until he’d given him the biggest hug ever. I wish it were all so simple. Did you go to summer camp when you were a kid? I’ll share my camp experience in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. In the early 1960s, men were men and, as the saying goes, “women were glad of it.” John Wayne was hitting his stride, and Rock Hudson was a ruggedly closeted heartthrob. Although men ruled their homes, as in the Cleaver household in Leave it to Beaver and the Stone household in the Donna Reed Show, the “man as tough guy” image was often overshadowed by the “man as vulnerable hero” (Jimmy Stewart), as a debonair ladies’ man (David Niven), and as a suave secret agent (Sean Connery as James Bond). Villains, usually played by Lee Marvin or Edward G. Robinson, were exaggerated masculine images, but they were bad guys and often looked like nothing more than childish bullies on the screen. Fuzzy was tougher by a mile. I was jealous of the tough guys, but I don’t think I ever really wanted to be one. Not that I liked being the skinny weakling, but I learned early on that strength isn’t always measured by the size of one’s biceps. In other words, I knew what a “real man” was. Of course, the lesson reached me through the medium of television. The first male role model I recall was Chuck Connors’ character in The Rifleman: Lucas McCain. It’s funny, as I write this I am sitting at my favorite bar intermittently reading Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir, Fun Home. On a page where the child Alison is oblivious to her father’s attraction for young men, there appears on a TV screen some scenes from The Rifleman. Somehow a book about coming to grips with one’s sexuality—and one’s father’s—fits in a chapter about real men. Lucas McCain was a real man, and not because he carried his eponymous weapon. The lessons I gleaned from McCain, the ones he taught his son (played by Johnny Crawford, a kid whose looks I was jealous of), were about helping those less fortunate, obtaining justice for those denied, and choosing delayed (over instant) gratification. Lucas McCain had the coolest gun, but he tried not to use it. To use your primary weapon outside of absolute necessity is to abuse it. I don’t think McCain ever said that, but he could have. Guns were an integral part of play for the boys in my neighborhood. We’d choose sides—good guys versus bad guys—and divvy up the arsenal of toy revolvers, automatics, and rifles. Sometimes as many as eight or ten guys would join the battle. But when I was by myself I played with plastic soldiers.

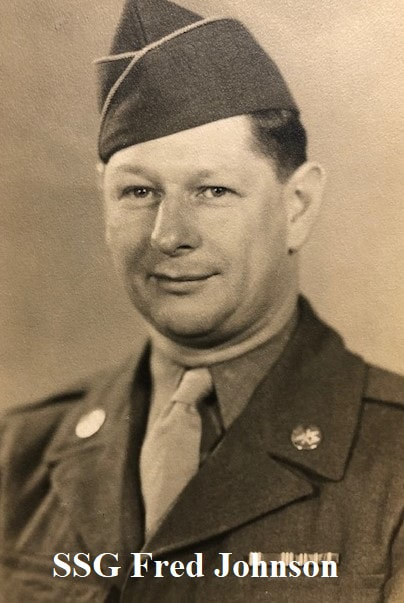

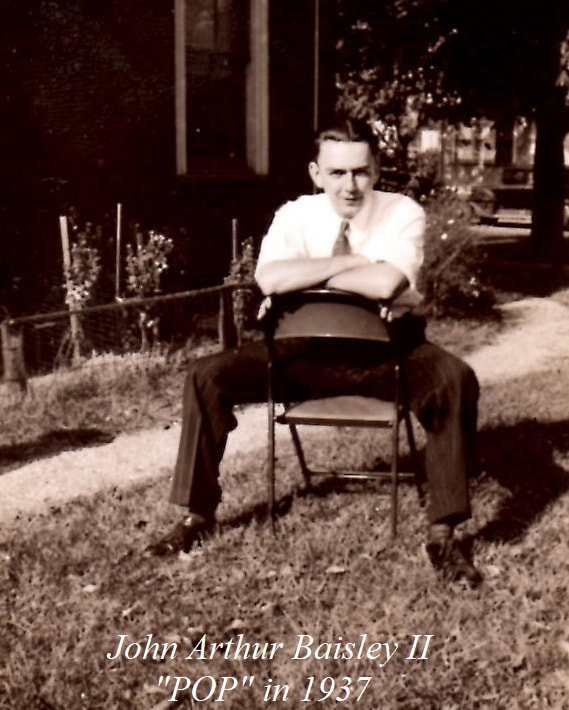

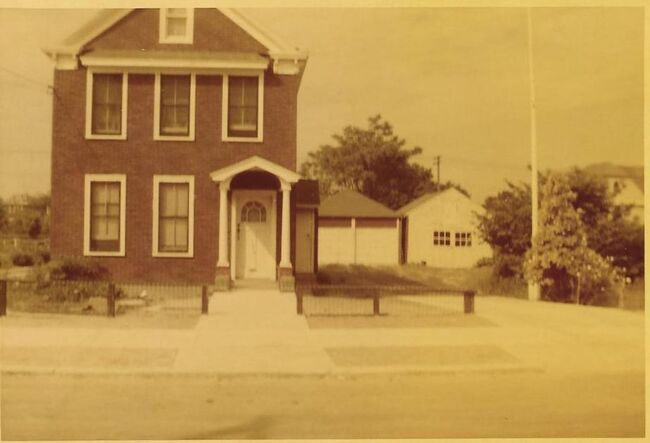

Three nights later, while kids and parents were still talking about Combat!, ABC also rolled out a quieter, more introspective war series: The Gallant Men. It featured a squad of G.I.s fighting their way through Italy in 1943. The Gallant Men was an unusual war show in that one of the main characters was a war correspondent. I don’t remember whether the man was a pacifist or not. At that time I had no clue what that word meant. But I never saw him carry a gun, only a pencil and a pad or a typewriter. What courage, I thought. What determination. To get the story out to the world. To put the truth above your own safety. That’s what I wanted to do. Most kids’ first “when I grow up” job was firefighter or veterinarian or baseball player. Mine was war correspondent. I found a copy of Ernie Pyle’s Brave Men in, of all places, my brother’s library. I wanted to bring stories back from a war I didn’t even know existed at the time. I took it so far that when playing The Game of Life I’d desperately want to land on the spot that made one a journalist. That dream ended after a two-year stint as gossip columnist, under a pen name, for my college newspaper. The Gallant Men lasted only one year. Nobody watched it. When I’d tell the gang about the latest episode they’d get on me about watching a sissified version of a war show. Judgment reached a new low when I, as much a war lover as anyone, was chastised for choosing the wrong WWII TV series. I guess real men were watching Combat!. Hollywood’s role models changed over the years, but my one constant image of a real man was my dad. Pop was never that tall, barely topping out at 5’10”, although he shrank considerably in the waning years of his life. He was more wiry than muscular, though he managed to play a little semi-pro football in his young adulthood. We never had a gun in our house, but Pop was reputed to be a crack shot with a .22 when hunting rats on Pumpkin Patch, a sandbar off the coast of Canarsie Pier. In other words, he did traditionally manly things, but he did them in his own non-traditional ways. Pop was a bundle of contradictions. He was a fiscal conservative, a political moderate, and a staunch union man, all the while voting straight ticket Republican his whole life. Actually, that wasn’t too much of a stretch. Pop lived in an era whose Republican stars—Eisenhower, Nixon, Rockefeller, even Barry Goldwater—would be vilified as flaming liberals by today’s GOP standards. Pop was no liberal, but he was no party’s fool either. The same could be said of his religion. In the jargon of his day, Pop was a fundamentalist. That meant he adhered to certain doctrines such as biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth of Jesus Christ, Jesus’ death on behalf of humanity, and Jesus’ physical resurrection and eventual return. Other than avoiding habits like drinking and smoking, Pop’s fundamentalism didn’t meddle much in people’s lives. Still, the fundamentalism of Pop’s day did give rise to contemporary evangelicalism, even though evangelicals in the 1950s were considered by fundamentalists to be only slightly right of the worst of the liberals. Again, Pop’s personal expression of faith did not toe the party line. One “Pop story” stands out in my memory as an example of that faith. It happened on a Sunday afternoon when Pop said, after a service at Grace Church, “Don’t put your play clothes on after dinner. We’re going out again.” (No matter that I was probably fifteen by then, whatever I changed into after church was always “play clothes.”) Whenever Pop spoke like that, I knew an adventure was in store. Pop’s adventures could be pretty unusual. Like the time on a family vacation somewhere in New England when we visited a waterfall. Pop noticed a series of rocks jutting out to the middle of the river just above the falls. “Phil, do you think you can climb out there?” “Sure thing, Pop!” With a twelve-year-old’s bravado, I risked life and limb maneuvering myself to a precarious perch above the raging waters. I even hung on with my feet alone, raising my hands triumphantly as Pop got out his camera...which he turned to the shore as he yelled, “Hey Fran! Look what your son is doing!” He wanted to capture Mom’s terrified reaction. This day’s adventure, beginning right after Sunday dinner, surprised me more than most. We dashed to the Oldsmobile Vista Cruiser and headed toward the Belt Parkway. Pretty soon we were in a section of Queens I’d only seen before in passing. We never stopped there. At least I’d never stopped there. Exiting the parkway and winding through city streets until we ended up back near the Belt, we pulled up to a white clapboard-sided church. Pop parked the Olds, and we walked toward the front door. “What church is this?” I asked. “I know some people who go here,” Pop answered. “They asked me to serve on an ordination council. Today that young man is going to be ordained as a minister.” I didn’t recognize the name on the announcement board in front of the building. It wasn’t a Baptist Church, like the ones on the Island we played volleyball against. It wasn’t another Independent Fundamental Church like Grace. It was a Church of Christ or something. The name wasn’t the only thing that was different. Once inside the door, staring at row after row of maple-stained pews, I noticed that Pop and I were the only two white faces in the building. “You know these people?” “Well, some of them. We go way back. I sing here sometimes. They wanted an impartial layperson to serve on the council, so they asked me. That’s why I was away some evenings last month.” Stunned, I sat beside Pop through the solemn service that was punctuated by outbursts of “Amen” and “Well” and “Yes, yes” along with loud, joyful, definitely not Grace Church-style, singing. “Who is Pop?” I wondered as we drove quietly back to Canarsie. There was no easy answer. But over the years I grew to respect and admire the quiet strength, courage, and contradictions that were the real man I knew as Pop. The visit to that church in Queens wasn’t my first lesson in black and white, as you’ll see in next week’s episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. I don’t know what you think of when you hear the word “gang” in a New York City context. There are a few possibilities. You could be thinking of the Leonardo DiCaprio and Daniel Day-Lewis movie, Gangs of New York. That movie contained elements of truth about New York in the decades leading up to the American Civil War, but it didn’t have much to do with my experience. Around the time the Five Points gangs were duking it out in lower Manhattan, my great-great grandparents were helping establish Grace Church in Brooklyn. You could be thinking of Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall, and their cronies, who populated the “Dead End Kids” and “Bowery Boys” movies. They epitomized the ideal of street-wise youth with hearts of gold hidden just beneath their rough exterior. Street-wise we were, I suppose. After all, most of us survived well into adulthood. But our hearts clung mostly to our sleeves rather than below a tough-guy image. That leaves the Sharks and the Jets of West Side Story. Those gangs carried switchblades, tire chains, and zip guns. People died in that play. People also sang and danced—a lot. Except for the tire chains and zip guns, that was our incarnation of the 93rd Street Gang. Toody Marciano showed us a switchblade once, but I think he was scared to carry it; something to do with it springing to life in his front pocket. We all understood—no switchblades. So, without weapons of street war, the 93rd Street Gang followed the lead of the Sharks and the Jets: we broke into song at the drop of a hat. Music dominated our lives. Why wouldn’t it? From Fats Domino and Buddy Holly to the Everly Brothers, Dion, and Little Richard to the Beach Boys, the Beatles, and the Stones; we lived in what is arguably the best musical epoch in history. And then there was Broadway. As far as I know, no member of the 93rd Gang saw a real live Broadway show during our collective childhood, but that didn’t matter. Show tunes topped the music charts in the 1950s. I didn't know it at the time, but the songs Pop sang around the house—when not practicing gospel tunes—songs like Surrey with the Fringe on Top and Some Enchanted Evening were straight from Broadway. I remember falling in love with show tunes when Isaac Bildersee Junior High’s orchestra first played excerpts from Fiddler on the Roof. I was in ecstasy and not just because I had a crush on a flute player. Until then I didn’t know music could bring out the emotions of a story better than words alone. I was hooked. The rest of the gang, being one or two years older than I, had known about this magic for a while. I remember the fierce competition between Billy Knudsen and Eddie Gentile over who could do the best Anthony Newley impression. I never joined in, being too timid for solos even in the gang, but I loved it. Today I often listen to the On Broadway channel on Sirius XM radio. No longer inhibited, with gusto I join Newley in belting What Kind of Fool Am I?. Billy went on to a long career in some giant corporation. Eddie made it into show business as a performer, choreographer, and teacher. And what kind of fool am I? I make occasional appearances in community theater musicals, sing in a folk duo, and write songs about dragons, Tiffany boxes, and a house in Canarsie that’s no longer there. My house was an anomaly in a Brooklyn neighborhood in the 1960s. My junior high friends called it a museum. I used to give tours of the attic and cellar. Yes, we had a cellar. It in no way resembled the basements most houses sit on. You reached the cellar by descending a rickety wooden stairway. No one ever took the time to install a light switch at the top of the stairs, so you used a flashlight to get to one of the pull chains on the bulbs that illuminated most of the cellar. Boxes and barrels lined the walls, and in the center of it all was an oil furnace. It smelled like, well, I guess the smell was oil. One time it smelled worse. Apparently the burner malfunctioned and the old contraption began emitting carbon monoxide. Mom was the first to smell it when she returned from driving one of the church ladies to a hairdresser appointment. Like most women of her era, before turning to a professional to deal with the potentially deadly problem, she called her husband. Eventually, even before I got home from school, a repair man came and fixed the furnace. Pop, as usual, was the hero. Near the furnace stood my favorite piece of cellar furniture, the wringer washer. For Mom, wash days were weekly events, each one consuming eight hours of loading, unloading, and wringing. This repetition led to hanging the wet clothes on a washline that stretched from the back corner of the house to a pulley high on a wooden utility-like pole in the backyard. Shirts, socks, and underwear flapped in the breeze some twenty feet above the ground, for all to see. I loved washdays in the summer when school was out. Perhaps my fondest memory of all was lying just inside the backdoor while Mom hung laundry on a sunny afternoon. I lay there with my head on a red pillow that was shaped like a horse. I think it actually was a horse when I was a preschooler. It was shaped for riding if the rider was a toddler. For a schoolkid it worked as a pillow. As the sun beat down on my skinny frame, I felt so warm, bathed in its radiance and Mom’s love. I suspect heaven has a backdoor; not for letting people in or out, but just for lying around on a stuffed horse and basking in light. The attic at 1304 was reached by ascending a steep stairway. Treasures awaited. Pirate chests filled with old clothes stood side-by side. Ancient lithographs of forgotten Baisleys lined up, each covered with a piece of white sheet or pillowcase. A dozen oil lamps filled the base of an old end table. Flatirons like soldiers at attention defended the area under the front window. A vacuum cleaner from the 1930s watched over a commode chair (yes, a chair with a toilet in it, the pot discreetly veiled by a flowered curtain). My friends loved that part of the tour best.

I had to change some numbers around for rhyme and rhythm purposes, but you’ll figure it out. If you listen carefully toward the end of the third verse, you just might hear the 93rd Street gang. PART OF MY HEART Words and music by Philip C. Baisley © 2012 Baisltunes (ASCAP) (inspired by William Trevor’s short story The Piano Tuner’s Wıves) There were doilies on the tables on both sides of the sofa And a stain deep in the paper near the clock upon the wall If you listened you could hear the mice gnawing on the plaster Somewhere in the space between my bedroom and the hall Every Christmas Eve there was a tree, it reached as high as heaven And oatmeal raisin cookies for when Santa came to call Each wear spot on the carpet, every finger-painted doorknob Just the way we left them, in my mind I see them all But thirteen-ten North Ninth Street can’t be Googled, can’t be plotted By any satellite or GPS found anywhere It’s just a few apartments, thirteen-two –eight –twelve and twenty But somewhere in the middle part of my heart’s still beating there They said, “You can’t go home again,” I guess they really meant it When someone takes a bulldozer and buries memories But I still hear the Ninth Street Gang singin’ Sherry Baby And I still smell the sweet perfume of the evergreens But thirteen-ten North Ninth Street can’t be Googled, can’t be plotted By any satellite or GPS found anywhere It’s just a few apartments, thirteen-two –eight –twelve and twenty But somewhere in the middle part of my heart’s still beating there No ghost can haunt a place when there’s no place a ghost can haunt No self-respecting spectre would appear There’s not a speck of dust to mark the place I spent my childhood There’s just a part of my heart I left there And thirteen-ten North Ninth Street can’t be Googled, can’t be plotted By any satellite or GPS found anywhere It’s just a few apartments, thirteen-two –eight –twelve and twenty But somewhere in the middle part of my heart’s still beating there What does the term “real man” mean to you? You’ll meet my role model of a real man in the next episode of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed