|

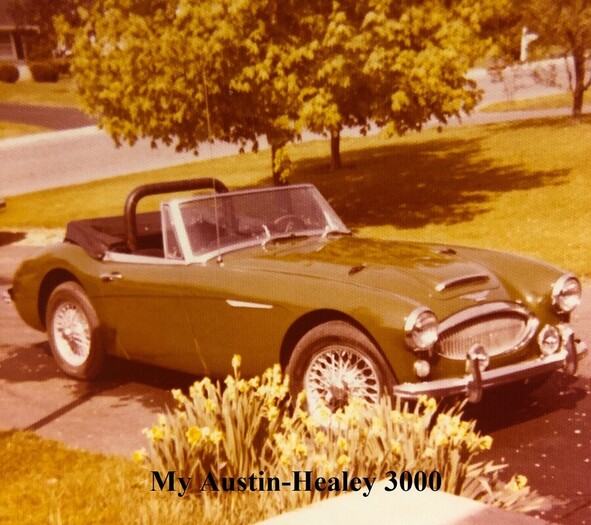

My first couple of decades held a lot of judgment. I grew up in a religion that preached the claim of its founder: “Judge not, that ye be not judged.” Yet every move we made in church or, were we well known enough in the Christian community, on the street was weighed in tightly regulated balances and often, if not usually, found wanting. At church, I lived in a fishbowl almost as clear and prominent as that of the pastor’s family. I had to be more than nice, more than good; I had to be perfect. I wasn’t. Bible college made it worse. There I encountered judgment based on a set of rules the likes of which made growing up in Grace Church a free-for-all of sin. We were judged based on our wardrobe: flared-leg jeans and bell bottoms were okay for meals but not for class, and never for church, and straight-leg jeans were okay for off-campus work but never for meals or anything else on campus. We were judged on the sexuality implicit in actions like holding hands (only for officially engaged couples), kissing (only for married couples), and all other physical displays of affection (never, except what you could do on a back road amid the Amish farms). During my junior year, newly accredited Lancaster Bible College (LBC) took in a host of transfer students from an unaccredited fundamentalist institution. They, in humble Christian fashion, prided themselves on their superior spirituality. They frequently spoke words of rebuke—literally; they’d walk across campus and say, “I rebuke you for thus and so”—to students who kept LBC’s laws but not the higher standards of the transfer students’ alma mater. Never before, and only rarely since, have I felt so inadequate as a human being and a Christian. The thing is, through it all I remained true to the way I was brought up. I was raised in an alcohol-free home. Before I was even close to drinking age, Pop took me aside one day and told me his thoughts on alcohol. He said that God created the ingredients, and so they were good. And there’s nothing sinful in having a beer or a glass of wine. “Just don’t get carried away and lose your good judgment.” Pop also reminded me that alcoholic beverages would never be welcome in his house. Mom’s father had had a drinking problem, so out of respect for her, no alcohol at home ever. Those words became part of my life. Even when I was old enough to drink, I didn’t. The legal drinking age in New York, prior to the establishment of national drinking standards, was eighteen. So, the summer after my freshman year at college, I returned to Brooklyn of legal age. But I didn’t drink. One day that summer, my good buddy, Scott, told me that a favorite band of ours, the Modern Jazz Quartet, was playing at the legendary SoHo venue, the Half Note Club. Being nineteen and eighteen respectively, Scott and I were old enough to go. Of course I told Mom and Pop about it. After all, we were going to a bar. Pop told me to be safe and not to be stupid, and to have a good time. We did. We took the Subway to the Half Note and entered the place with due reverence. Being early, we got a table next to the bar and only one row of tables from the stage. Purchasing alcohol was required for admission, so Scott and I each bought a beer. Scott ordered; I knew nothing about beer. Scott nursed his beer and mine—I never touched a drop—through the entire set by the MJQ. Man, they were awesome. This was John Lewis, Milt Jackson, Percy Heath, and Connie Kay in their prime. Smooth. Melodic. Improvisation with just the right amount of restraint. The music wasn’t even the best part of the night. Our seats were amazing. I mentioned we were next to the bar. On the last stool, the one closest to us, sat comedian Nipsey Russell, whom we’d seen on TV a hundred times. Right in front of me, at the table nearest the stage, sat legendary jazz saxophonist Stan Getz. We were in heaven. As much as Bible college may have tried to convince me otherwise, admission to heaven is not about alcohol or bars or jazz. Under the threat of judging stares, had the college administration heard about my evening at the Club, I felt free to follow my conscience with the blessing of my dad, whose righteousness surpassed most Christians I knew. That’s the way I was raised. Although he never wrote them on paper for me to tuck into my Scofield Reference Bible, Pop’s three guiding principles etched themselves into my heart:

Somehow, in spite of that freedom, judgment hung over me like a storm cloud. And it stayed with me, albeit under the radar, for thirty-three years after graduation; otherwise known as my first marriage. For most of those years I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was falling short, but I had no proof. Then came Sandy’s departure and the ensuing twenty-two page list of my faults. I guess my gut instinct was right. Or maybe I’m really that bad a person. I wish I knew. Thinking back, there was a person worse than I: Isaac, the other man upstairs. He terrorized the children of the neighborhood from his bedroom window, and he made life hell for my friends and me if we ventured into his side of the yard. Perhaps this is the ultimate tale of judgment, or maybe justice. Maybe it was karma at its best. After spending a week or two at home the summer after my freshman year at LBC, I left for summer missionary work in Richmond, Virginia. One July evening, after a delicious pot roast dinner with my host family, I received a phone call from Mom. She gave me the news, not necessarily sad, that Isaac had died. She had found him on the floor of his living room. Immediately I called Morty Epstein. Earlier that summer break, between my arrival home from LBC and my trip to Virginia, Morty stopped by to see me. It must have been mid-May because New York public schools were still in session, and Morty was on his way home from track practice. Morty drove into the yard—Isaac’s side since that’s where the driveway was—and parked his mint condition 1964 ½ Ford Mustang at the edge of the concrete apron. I’m sure he only planned to be there long enough to say hi and decide where we’d be hanging out that week. He walked around the house to the back door, our usual entrance. A few minutes into our visit, Mom reminded Morty that it was four o’clock and Isaac would be home from the docks at any minute. Knowing what justice the man upstairs would exact upon our family if the sanctity of his driveway were infringed, Morty turned toward the door. Too late. Crash! The sound of a Mustang fender assuming an accordion shape exploded through the open dining room window. Isaac, whose eyesight was 20/20 with corrective lenses, and who had plenty of room to negotiate a path around Morty’s pride and joy, had taken stock of the situation and rammed his Pontiac into the Mustang. Morty was livid. He knew what had happened without having seen it. He rushed toward the door, but Mom beat him to it. “Morty, don’t do anything rash. Let me explain something to you.” Most kids my age would have assumed their mother was about to issue some calming instructions on how to deal diplomatically with the situation at hand. Someone else’s mom might have told Morty to wait inside while she assessed the accident scene and confronted Isaac. Not my mom. Mom led Morty to the old sofa bed that occupied the west wall of the dining room, set him down, and sat beside him. Then, in her most evangelistic voice, she explained the truth behind Isaac’s assault on Morty’s beloved car. “Morty, you’ve got to understand that Isaac isn’t a Christian,” she began. Morty’s face revealed the workings of his mind, “Of course he’s a Christian. He’s not Jewish. What else is there?” Mom went on, “Isaac doesn’t have the Holy Spirit to guide him in situations like this.” Morty’s mind again, “What the fuck is a holy spirit?” And back to Mom, “Isaac didn’t really know what he was doing because he doesn’t have the Spirit to show him right from wrong, so even if you went out and beat him up, it wouldn’t help. Just wait till he goes inside and then check on your car. Phil’s dad and I will cover any expenses your insurance won’t pay for. And Morty, as for Isaac and his meanness, don’t worry. God will take care of it.” And that was that. Mom’s theologically incomprehensible argument stopped Morty in his tracks. He waited a few minutes, and then we all went out to survey the damage. One rear fender was badly smashed, but the Mustang was drivable. Morty agreed he would not retaliate against Isaac, and he went home to deal with his insurance company. With some TLC from a nearby body shop, the Mustang was good as new within a week. Knowing how the Mustang’s attempted murder still irked Morty, even though he’d followed Mom’s advice, when I got that phone call I decided my track team buddy deserved to hear about Isaac’s demise. Morty himself answered the phone that evening. After exchanging pleasantries and basic information about our summers, I told him about Isaac’s passing from a heart attack right on his living room floor. Morty couldn’t hold his excitement. “Wait!” I could almost see Morty’s hand over the mouthpiece as he turned away from the phone. “Ma! Hey, Ma! Remember when Isaac hit my car and Mrs. Baisley said that God would take care of it. Well, it’s been taken care of.” Judgment? Karma? Or just good luck (Morty’s perspective) or bad luck (Isaac’s perspective). I never fully subscribed to the fundamentalist Protestant idea that God was constantly watching and judging our actions, or even saving them up for some future Judgment Day. I can understand God keeping an eye on us, mostly for our own protection; guiding us toward the good, even when it temporarily causes us pain; but the idea that God “took care of” Isaac, as appropriate as it sounded, was not part of my theology. I laughed with Morty, who, I’m sure, didn’t own that theology either. But if God didn’t judge Isaac’s meanness and condemn him to a slightly early death, then why have I always felt that I was being judged? For a lifetime I’ve put off thinking about this. Maybe it’s time to start. Mom and Pop were the best parents a kid could have. They were conservative theologically, which was not a bad thing in those days. Back then, conservatism meant taking the Bible seriously but not fanatically. It meant celebrating Christmas because Jesus was God in the flesh but not a right wing champion. It meant believing that “we” were going to heaven but welcoming “them” because God loved them too. Somehow, we figured God was going to sort it out. Mom and Pop were also quite liberal, at least in their parenting. I doubt I’d ever have felt so comfortable in such diverse settings had not Mom and Pop allowed me to go anywhere at any time with anyone, as long as I kept them informed. They trusted me. So where did I learn judgment? Was it in the 93rd Street Gang? Hell, we were constantly swearing at each other, “ranking” each other out, and insulting each other’s parentage. But even though I sometimes felt like an outsider due to my small stature and younger age, I always knew I was part of the Gang; and that meant I was somebody. I guess the place I felt most judged was the place that felt most like my second home: the church. Church was where I was expected to live up to standards, not always articulated, simply because I was the “little Baisley boy.” Kind of paradoxical isn’t it? In the place I felt most secure, I also felt most judged. As part of a congregation that reveled in its freedom, I was held to standards that restricted my behavior to a litany of unwritten rules. I loved my church, but I probably hated it too. And here’s the kicker. I believed, and still believe, that the church is not a building topped with a steeple. The church is people. It’s Peter and John and Mary and Paul from biblical times. It’s the saints in the windows of Holy Family Church in Canarsie. It’s the saints and sinners who showed up at Grace Church on Sunday. But it’s one more thing, and this is where Judgment Day makes its appearance in every calendar year. The church is also me. I am indelibly connected with the good and the bad of that ancient institution. The judgment I felt growing up, and often feel today, is part and parcel with the church I love. To clarify, maybe I need to quote the great philosopher, Pogo, from the old comic strip of the same name. The venerable possum once said, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” If I am the church, then this feeling of judgment comes from… well, from me. Green Day sang, “Do you know your enemy?” After thirty-eight chapters covering twenty-one years, maybe I do. There’s another meaning to the word judgment; it’s “to discern.” I did a lot of stupid, selfish, and occasionally unethical if not illegal things in my early days. It takes a bit of healthy judgment—discernment—to sort them all out. Writing this memoir has helped me see that. But maybe now the time has come for me to judge once and for all that I’m neither worse nor better than just about every kid who grew up on the mean and wonderful streets of American cities in the fifties and sixties. Different? You bet I was, and now I’m proud of it. But worse? Fuhgedaboudit. ****************************** We’ve come to the end of my memoir. What started as a few stories written down for my children has turned into over 70,000 words. Still, with the publication of almost every episode, I get a message from some old friend asking why I hadn’t included such and such story. Well, some I simply chose not to tell; they didn’t fit a certain theme or chapter. Others, like the time I drove a carload of track team friends on a boyish prank that ended with us stopped by the SWAT team, I must have worked hard to erase from my memory. So, in true Canarsie fashion, I’ll make you a deal. I’ll add to the memoir at least once a month with more tales from my old Canarsie experience. It’ll be a good way to keep you interested in my next writing project: a crime novel set in 1904 Brooklyn and Manhattan, with scenes in Canarsie. I’d like you to do something too. Please share your stories with me. I’ll add them to the blog, giving you full credit, of course; or, if you wish, keep them just between you and me. I want to let the world know what a great place Canarsie was, and often still is. Just contact me through this blog, or via email ([email protected]) or through Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. Send me your “Tales of a Canarsie Kid.” So, this isn’t good-bye. It’s just, see ya’ later. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. Regrets, I've had a few, but then again, too few to mention. So wrote Paul Anka when he was twenty-six. It’s funny that a person would consider the regrets of a lifetime when he had lived so little of it. I, on the other hand, have lived more than twice that long; but when it comes down to it, my regrets list is still pretty short. It might be a good time to think about them. Before enumerating my regrets, I want to reflect on that word for a moment. Regret. What does it mean to regret something? According to Merriam-Webster online, to regret is to “mourn the loss or death of,” to “miss very much,” or to “be very sorry for.” Looking at a regrets list I compiled in January 2017, I can find things in common with those definitions. Let’s start with the earliest and easiest one, which harkens back to fall 1969. I should have run stronger in cross-country my senior year at Canarsie High. For that matter, I should have tried a little harder in every varsity sport in which I participated. I wasn’t a bad runner in high school. I had the speed, in shorts bursts, to be a decent city-class long and triple jumper. I had the stamina to complete multiple one-mile runs during cross-country practice. I had the drive to practice every day even while recovering from bronchitis. What I didn’t have was a runner’s heart. I know I could have tried just a little harder. The few times I did, and I achieved the proverbial “second wind,” were pure euphoria. I could have reached that high more often. I remember one time, decades after high school, when I made one of my occasional restarts at distance running. I set out on a weekday afternoon with snow falling in slow thick flakes. I planned to run an easy 5k, but I just couldn’t stop. The snow, the brisk air without a breeze, the feeling that my legs would last forever. I kept running. As darkness fell I made my way back home, walking the last half mile and still feeling great. The next day I retraced the run: 9.1 miles non-stop. Guys like Allan and Paul on my high school team did that with regularity. They never quit before they’d given their all. I truly am sorry I gave so little so often. I have the same regret regarding my soccer playing in college. I should have played my senior year. I had never played soccer—football to the rest of the world—before enrolling at Lancaster Bible College. I was a distance runner and a jumper in high school and a fair football and hockey player in street versions of those sports. I arrived at Lancaster to learn the tiny (less than 120 students when I was a freshman) Bible college only had the personnel and the finances to field a men’s soccer team and a women’s field hockey team. Before I graduated we had intercollegiate basketball teams as well. Since I was still in good shape from track, and since soccer was mostly running—aimlessly it looked as I tried to study it—I went out for soccer. Learning the basic footwork was fairly easy, and I had the requisite speed and stamina, so they made me a second-string midfielder, which they called by the American football name, halfback. Mostly I just ran around trying to get the ball away from an opponent and pass it to one of our guys. After observing me in practice and in the little playing time I got that season, during spring training the coach moved me up to wing. He’d noticed that I was primarily left-footed. That’s not as good in soccer as being fully ambidextrous, but I was the only strong lefty on the team, and Coach figured I might be of some use getting the ball to our nimble guys in the center. I caught on pretty quickly at wing and when the season began in August, I was the starter on the left side. For two years I was the LBC Chargers’ starting left wing. I wasn’t great, but I had my moments, scoring a few assists each year and the occasional goal. I think my finest moment occurred in a Homecoming game. I had taken the ball from a defender at midfield and began dribbling down the left sideline. Managing to evade another defender, I could see Robin breaking toward the goal. Summoning up all my left-footed strength, I kicked a long pass high in the air and behind the goal. In true Beckham style, about three years before Beckham was born, the ball bent back above the field and sailed right to the spot where Robin was running. He headed it into the goal without losing a step. My parents were in the stands, and I don’t think Pop was ever prouder of me. Our soccer coach retired the end of that season. Soon word got around that the incoming coach was determined that LBC’s tradition of losing most of their games would be no more. Through tough practices and strict discipline, our team would be forged into winners. I liked winning, even though we didn’t win very often. But did I want to run more, practice my dribbling to exhaustion, and—worst of all—give up precious time with my latest girlfriend in order to become a winner? Once again, at a time when I could have pushed harder and achieved significant athletic success, I wimped out. Or maybe I just chose love over soccer. I wish I’d played my senior year. How good could I have gotten with a tougher coach? And why did I have to spend so much time with that girl? There’s a regret for you. I regret that I chose a series of semi-long-term relationships with women I expected to marry rather than simply having fun getting to know a lot of people. My favorite month in all my years at LBC was April 1973. My latest pre-engagement girlfriend had just broken up with me. With about six weeks of school left, I posed a challenge to myself: how many different girls could I date before the end of the semester? The final tally was thirteen, including donuts and coffee with a graduate assistant after an evening class. For the first time in my life, dating was fun. No strings. No commitments. No reason for being together except to have a good time. True, there were no steamy-windshield make out sessions in the cornfields on Butter Road, only one quick peck after one perfect date; but everything else was better. Why couldn’t I have discovered that sooner? And why did I not learn from that month, falling back into my old ways just a few months later, and ending my career as a college athlete. Regrets are hard to write about. They’re not funny like sledding spills or grouchy old neighbors. While enumerating these incidents felt like fun at the time, writing about the details brings me about as much joy as a trip to the dentist. Still, the dentist serves a valuable purpose, and I hope these recollections do as well. Because I quit the LBC soccer team, I was able to spend my senior year pursuing the woman who became my wife. Of course, she was not the one I quit the team for. Sandy was only a month younger than I, but she entered college as a freshman after spending three years in the workforce at a Kresge lunch counter. We met on a November evening, the day after her birthday. Some friends and I, including Sandy’s roommate, were talking about going to a Hershey Bears hockey game. Sandy walked in, overheard us, and said, “I’ve never been to a hockey game. Can I go too?” Ever the suave one, I replied, “Sure! If you pay your own way.” It might have been our first date, but we never got to the hockey game. Russ and I ended up working very late delivering a large organ to a house in Maryland. The best I could do was call Sandy and express my regrets. Our second date was in January, and it ended with our wreck on US30 that earned the four of us a week’s “campus,” which I’ve previously described. With one broken date and one disaster by mid-January, Sandy and I moved swiftly to the expected conclusion: we got engaged, diamond ring and all, during spring break. The wedding was August 17th. We were both almost twenty-two when we got married. That’s not necessarily too young, if you’ve spent some time getting to know each other. We didn’t. Even our premarital counseling sessions with Sandy’s pastor didn’t make a dent in our lack of awareness of basic issues like how differently our parents related to each other, and that made all the difference in our marriage. To give you an idea of how immense were the gaps in our knowledge of each other, I’ll share a story that came from a telephone conversation between Sandy and me. It concerned our move from Indiana to Oregon in 1994. While our household goods were traveling in a horse trailer, Sandy and I drove our 1991 Ford Festiva and 1993 Pontiac Grand Am, each one carrying one of our children as well. We made regular bathroom, gasoline, and meal stops. Traveling across Interstate 90, we began seeing signs for Wall Drug Store as soon as we entered South Dakota. Wall Drugs may be the world’s first superstore. Long before Wal-Marts took up city blocks, this roadside landmark started selling just about everything from its small town pharmacy roots. The store’s claim to fame was its offer of free ice water to parched Midwestern travelers. I’d heard about Wall Drug from my parents years before, although they'd never been there. Sandy had never heard of the place. So, at a rest stop somewhere east of Wall, She asked me about those green and yellow “Wall Drug” billboards. I explained to her that Wall Drug was an overgrown drugstore that was kind of like a big Wal-Mart, and how it had grown from a small store to a bit of rural Americana. She thanked me for the explanation and that was it, or so I thought. Fast forward to the phone conversation. Sandy said, “Do you remember on our way to Oregon when I asked about Wall Drug?” “Sure,” I replied. “I really wanted to go there.” “Why didn’t you say so?” “The way you spoke, I thought you didn’t want to see it.” “Oh. I figured I answered your question. I didn’t care one way or the other, but if you’d wanted to go I’d’ve gladly stopped.” And that was it. One little piece of information about our families of origin that decades of marriage without really communicating failed to uncover. In Sandy’s home, what Dad said was done with little or no space for rebuttal. With Mom and Pop it was more democratic. For thirty-three years we tried to live up to our expectation of each other’s parents’ marriages, without ever talking about those marriages. We were doomed. My regret, at this point is not our marriage, but it is that we should have remained friends in college and never taken the marriage step. I know that sounds convoluted. How can you regret getting married but not regret a failed 33-year marriage? It’s not that simple. It never is. I talked to Sandy a few years ago, and I brought up the “should have remained friends” conversation. I said we were wrong about that. Our marriage produced two amazing kids, who have overcome tremendous obstacles—some of their own making—to become very fine human beings. We have four wonderful grandchildren. We’ve instilled in them all some values that have withstood our failures. That is nothing to regret. I don’t regret the friendship Sandy and I have now. It may be strained a bit when Jen and Thomas and I get together with Sandy and our daughter, Kellyn, and her kids, but it’s worth keeping. Maybe friends are what we should always have been. I can’t answer that. I’m glad we’re friends now, and I’ll take that. Sandy figures into my last two regrets, although she is not the reason for either. They fit in the shoulda, woulda, coulda category, which I’m inventing just for them. First, we should have bought that house in New Holland. After our August wedding, Sandy and I moved into a tiny, maybe 50’ x 10’, trailer. Calling it a “mobile home” would be too much of a stretch. We made it a cute little love nest thanks to some furniture I bought from a coworker at the fried chicken factory where I worked, using the last of my inheritance from good ol’ Uncle Charlie. The problems began no sooner than the nearby cornfields were harvested. I woke up one morning to grab some milk and Entenmann’s chocolate-covered donuts only to find the chocolate had been gnawed off every donut in the top layer. Mice! I was terrified of them ever since a scary childhood incident with a very large rat back in Canarsie. “Sandy! We have to move!” In December we moved into a third floor apartment in a brand new faux-Tudor complex in New Holland, PA, walking distance from the chicken place. Sandy got a job there too. We were doing pretty well for a young couple just starting out. After about a year, when it looked like our future in eastern Lancaster County was secure, we took a walk through the neighborhood and spied a realtor’s sign on a brick half-duplex between our apartment and the factory. We had no down payment saved up, but we figure the monthly payment would be no more than we were paying in rent. We checked it out. The house was adorable. Two bedrooms--one for our anticipated first child, who didn’t really show up for another six years--a cute little yard, a sunny kitchen; it was a great little place for a reasonable price. We talked to Mom and Pop about the down payment. They drove over from their new home in Leola and took a look. They had a lot of questions. I think if we had pushed a little harder they’d have given us the money. Had they, we might still be living in Pennsylvania. Who knows? But they didn’t, and we took what little we did have and traded our 1969 BMW 1600 for a more family friendly 1975 BMW Bavaria. What if we’d waited a little longer, saved up a little more money, and then asked Mom and Pop for the rest? What if we’d asked them one more time for the down payment on the duplex? We’d have become homeowners, the American dream and Sandy’s heart’s desire. A house would have tied us to one locale, which would have made too difficult to move to places like Williamsport, PA; Pittsburgh; Springfield, OH; Greenfield, IN; and Newberg, OR. Those many moves were long a part of Sandy’s dissatisfaction with our marriage. I’d have moved up in the corporate ranks and made a lot more money at a younger age. Sandy could have gotten her wish and never had to work to help with our support. She’d have become the stay-at-home mom she always wanted to be. Maybe we’d still be together. Yeah, I regret not buying that house; but I think I’d still have made the moves necessary to get me into the kind of ministry I now enjoy. I think our kids are stronger because of the moves than if they’d been raised in one place with only one perspective of the world. I don’t know if Sandy would have been happier or not. They say a house is not necessarily a home. It’s not a guaranteed recipe for happiness either. So we bought the Bavaria. Man, that thing could accelerate. I wanted the new model, the 530i, which I could have ordered with a stick shift. We couldn’t afford it. We took the on-the-lot, end-of-year Bavaria with an automatic transmission. I thought it would be as much fun as the 1600. I was wrong. My favorite thing to do with the Bavaria was to get it on the highway, cruising at the new federal speed limit of 55 mph, and kick it down a gear. That metallic blue beast would jerk your neck back as it accelerated to 90 in a split second, making passing a semi a total breeze. And breeze is what you’d get if the sunroof was open. The problem with the Bavaria, aside from the monthly payments approximately equal to a small brick duplex, was that it was a lemon. I stuck with BMW because my 1600 was so reliable. In less than a year, the Bavaria was in the shop three times. Then the paint started fading and cracking. At the manufacturer’s expense we had to get a new paint job. By that time, I was done. We traded the Bavaria for a 1976 Volkswagen Rabbit (for Sandy) and a 1967 Austin-Healey 3000 (for me). Thus began a lifetime of trading cars every three or four years. If I regret not buying the brick duplex in New Holland, I regret parting with the Bavaria even more. By the time we traded it, the bugs had been worked out. The paint job may have devalued the car temporarily, but eventually time would have evened things out. We might even have kept it long enough to need the four doors and extra backseat room for a car seat. And I’d have been ready when they finally did away with the 55 mph national speed limit. Shoulda, would, coulda; that’s what regrets are really about. We are sad about things we missed because we were doing something else. We are disappointed things didn’t turn out the way we wished because of a decision we made or failed to make. We are sorry for our sins of omission or commission. The funny things is, as I look back over six decades, I can find so few things I truly regret; and the last one was in 1976 when I was twenty-three years old. Maybe Paul Anka was right when he, as an old soul of twenty-six, wrote: Regrets, I've had a few, but then again, too few to mention. I began this memoir recalling times I’ve felt judged by others. Next week we’ll come full circle with Judgment Day, Episode Thirty-eight of Tales of a Canarsie Boy. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed