|

My first couple of decades held a lot of judgment. I grew up in a religion that preached the claim of its founder: “Judge not, that ye be not judged.” Yet every move we made in church or, were we well known enough in the Christian community, on the street was weighed in tightly regulated balances and often, if not usually, found wanting. At church, I lived in a fishbowl almost as clear and prominent as that of the pastor’s family. I had to be more than nice, more than good; I had to be perfect. I wasn’t. Bible college made it worse. There I encountered judgment based on a set of rules the likes of which made growing up in Grace Church a free-for-all of sin. We were judged based on our wardrobe: flared-leg jeans and bell bottoms were okay for meals but not for class, and never for church, and straight-leg jeans were okay for off-campus work but never for meals or anything else on campus. We were judged on the sexuality implicit in actions like holding hands (only for officially engaged couples), kissing (only for married couples), and all other physical displays of affection (never, except what you could do on a back road amid the Amish farms). During my junior year, newly accredited Lancaster Bible College (LBC) took in a host of transfer students from an unaccredited fundamentalist institution. They, in humble Christian fashion, prided themselves on their superior spirituality. They frequently spoke words of rebuke—literally; they’d walk across campus and say, “I rebuke you for thus and so”—to students who kept LBC’s laws but not the higher standards of the transfer students’ alma mater. Never before, and only rarely since, have I felt so inadequate as a human being and a Christian. The thing is, through it all I remained true to the way I was brought up. I was raised in an alcohol-free home. Before I was even close to drinking age, Pop took me aside one day and told me his thoughts on alcohol. He said that God created the ingredients, and so they were good. And there’s nothing sinful in having a beer or a glass of wine. “Just don’t get carried away and lose your good judgment.” Pop also reminded me that alcoholic beverages would never be welcome in his house. Mom’s father had had a drinking problem, so out of respect for her, no alcohol at home ever. Those words became part of my life. Even when I was old enough to drink, I didn’t. The legal drinking age in New York, prior to the establishment of national drinking standards, was eighteen. So, the summer after my freshman year at college, I returned to Brooklyn of legal age. But I didn’t drink. One day that summer, my good buddy, Scott, told me that a favorite band of ours, the Modern Jazz Quartet, was playing at the legendary SoHo venue, the Half Note Club. Being nineteen and eighteen respectively, Scott and I were old enough to go. Of course I told Mom and Pop about it. After all, we were going to a bar. Pop told me to be safe and not to be stupid, and to have a good time. We did. We took the Subway to the Half Note and entered the place with due reverence. Being early, we got a table next to the bar and only one row of tables from the stage. Purchasing alcohol was required for admission, so Scott and I each bought a beer. Scott ordered; I knew nothing about beer. Scott nursed his beer and mine—I never touched a drop—through the entire set by the MJQ. Man, they were awesome. This was John Lewis, Milt Jackson, Percy Heath, and Connie Kay in their prime. Smooth. Melodic. Improvisation with just the right amount of restraint. The music wasn’t even the best part of the night. Our seats were amazing. I mentioned we were next to the bar. On the last stool, the one closest to us, sat comedian Nipsey Russell, whom we’d seen on TV a hundred times. Right in front of me, at the table nearest the stage, sat legendary jazz saxophonist Stan Getz. We were in heaven. As much as Bible college may have tried to convince me otherwise, admission to heaven is not about alcohol or bars or jazz. Under the threat of judging stares, had the college administration heard about my evening at the Club, I felt free to follow my conscience with the blessing of my dad, whose righteousness surpassed most Christians I knew. That’s the way I was raised. Although he never wrote them on paper for me to tuck into my Scofield Reference Bible, Pop’s three guiding principles etched themselves into my heart:

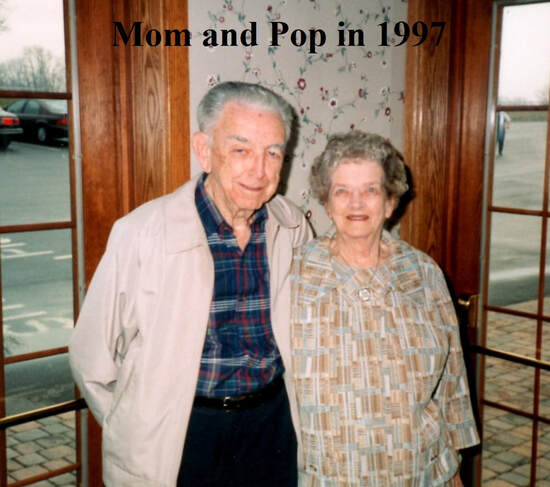

Somehow, in spite of that freedom, judgment hung over me like a storm cloud. And it stayed with me, albeit under the radar, for thirty-three years after graduation; otherwise known as my first marriage. For most of those years I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was falling short, but I had no proof. Then came Sandy’s departure and the ensuing twenty-two page list of my faults. I guess my gut instinct was right. Or maybe I’m really that bad a person. I wish I knew. Thinking back, there was a person worse than I: Isaac, the other man upstairs. He terrorized the children of the neighborhood from his bedroom window, and he made life hell for my friends and me if we ventured into his side of the yard. Perhaps this is the ultimate tale of judgment, or maybe justice. Maybe it was karma at its best. After spending a week or two at home the summer after my freshman year at LBC, I left for summer missionary work in Richmond, Virginia. One July evening, after a delicious pot roast dinner with my host family, I received a phone call from Mom. She gave me the news, not necessarily sad, that Isaac had died. She had found him on the floor of his living room. Immediately I called Morty Epstein. Earlier that summer break, between my arrival home from LBC and my trip to Virginia, Morty stopped by to see me. It must have been mid-May because New York public schools were still in session, and Morty was on his way home from track practice. Morty drove into the yard—Isaac’s side since that’s where the driveway was—and parked his mint condition 1964 ½ Ford Mustang at the edge of the concrete apron. I’m sure he only planned to be there long enough to say hi and decide where we’d be hanging out that week. He walked around the house to the back door, our usual entrance. A few minutes into our visit, Mom reminded Morty that it was four o’clock and Isaac would be home from the docks at any minute. Knowing what justice the man upstairs would exact upon our family if the sanctity of his driveway were infringed, Morty turned toward the door. Too late. Crash! The sound of a Mustang fender assuming an accordion shape exploded through the open dining room window. Isaac, whose eyesight was 20/20 with corrective lenses, and who had plenty of room to negotiate a path around Morty’s pride and joy, had taken stock of the situation and rammed his Pontiac into the Mustang. Morty was livid. He knew what had happened without having seen it. He rushed toward the door, but Mom beat him to it. “Morty, don’t do anything rash. Let me explain something to you.” Most kids my age would have assumed their mother was about to issue some calming instructions on how to deal diplomatically with the situation at hand. Someone else’s mom might have told Morty to wait inside while she assessed the accident scene and confronted Isaac. Not my mom. Mom led Morty to the old sofa bed that occupied the west wall of the dining room, set him down, and sat beside him. Then, in her most evangelistic voice, she explained the truth behind Isaac’s assault on Morty’s beloved car. “Morty, you’ve got to understand that Isaac isn’t a Christian,” she began. Morty’s face revealed the workings of his mind, “Of course he’s a Christian. He’s not Jewish. What else is there?” Mom went on, “Isaac doesn’t have the Holy Spirit to guide him in situations like this.” Morty’s mind again, “What the fuck is a holy spirit?” And back to Mom, “Isaac didn’t really know what he was doing because he doesn’t have the Spirit to show him right from wrong, so even if you went out and beat him up, it wouldn’t help. Just wait till he goes inside and then check on your car. Phil’s dad and I will cover any expenses your insurance won’t pay for. And Morty, as for Isaac and his meanness, don’t worry. God will take care of it.” And that was that. Mom’s theologically incomprehensible argument stopped Morty in his tracks. He waited a few minutes, and then we all went out to survey the damage. One rear fender was badly smashed, but the Mustang was drivable. Morty agreed he would not retaliate against Isaac, and he went home to deal with his insurance company. With some TLC from a nearby body shop, the Mustang was good as new within a week. Knowing how the Mustang’s attempted murder still irked Morty, even though he’d followed Mom’s advice, when I got that phone call I decided my track team buddy deserved to hear about Isaac’s demise. Morty himself answered the phone that evening. After exchanging pleasantries and basic information about our summers, I told him about Isaac’s passing from a heart attack right on his living room floor. Morty couldn’t hold his excitement. “Wait!” I could almost see Morty’s hand over the mouthpiece as he turned away from the phone. “Ma! Hey, Ma! Remember when Isaac hit my car and Mrs. Baisley said that God would take care of it. Well, it’s been taken care of.” Judgment? Karma? Or just good luck (Morty’s perspective) or bad luck (Isaac’s perspective). I never fully subscribed to the fundamentalist Protestant idea that God was constantly watching and judging our actions, or even saving them up for some future Judgment Day. I can understand God keeping an eye on us, mostly for our own protection; guiding us toward the good, even when it temporarily causes us pain; but the idea that God “took care of” Isaac, as appropriate as it sounded, was not part of my theology. I laughed with Morty, who, I’m sure, didn’t own that theology either. But if God didn’t judge Isaac’s meanness and condemn him to a slightly early death, then why have I always felt that I was being judged? For a lifetime I’ve put off thinking about this. Maybe it’s time to start. Mom and Pop were the best parents a kid could have. They were conservative theologically, which was not a bad thing in those days. Back then, conservatism meant taking the Bible seriously but not fanatically. It meant celebrating Christmas because Jesus was God in the flesh but not a right wing champion. It meant believing that “we” were going to heaven but welcoming “them” because God loved them too. Somehow, we figured God was going to sort it out. Mom and Pop were also quite liberal, at least in their parenting. I doubt I’d ever have felt so comfortable in such diverse settings had not Mom and Pop allowed me to go anywhere at any time with anyone, as long as I kept them informed. They trusted me. So where did I learn judgment? Was it in the 93rd Street Gang? Hell, we were constantly swearing at each other, “ranking” each other out, and insulting each other’s parentage. But even though I sometimes felt like an outsider due to my small stature and younger age, I always knew I was part of the Gang; and that meant I was somebody. I guess the place I felt most judged was the place that felt most like my second home: the church. Church was where I was expected to live up to standards, not always articulated, simply because I was the “little Baisley boy.” Kind of paradoxical isn’t it? In the place I felt most secure, I also felt most judged. As part of a congregation that reveled in its freedom, I was held to standards that restricted my behavior to a litany of unwritten rules. I loved my church, but I probably hated it too. And here’s the kicker. I believed, and still believe, that the church is not a building topped with a steeple. The church is people. It’s Peter and John and Mary and Paul from biblical times. It’s the saints in the windows of Holy Family Church in Canarsie. It’s the saints and sinners who showed up at Grace Church on Sunday. But it’s one more thing, and this is where Judgment Day makes its appearance in every calendar year. The church is also me. I am indelibly connected with the good and the bad of that ancient institution. The judgment I felt growing up, and often feel today, is part and parcel with the church I love. To clarify, maybe I need to quote the great philosopher, Pogo, from the old comic strip of the same name. The venerable possum once said, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” If I am the church, then this feeling of judgment comes from… well, from me. Green Day sang, “Do you know your enemy?” After thirty-eight chapters covering twenty-one years, maybe I do. There’s another meaning to the word judgment; it’s “to discern.” I did a lot of stupid, selfish, and occasionally unethical if not illegal things in my early days. It takes a bit of healthy judgment—discernment—to sort them all out. Writing this memoir has helped me see that. But maybe now the time has come for me to judge once and for all that I’m neither worse nor better than just about every kid who grew up on the mean and wonderful streets of American cities in the fifties and sixties. Different? You bet I was, and now I’m proud of it. But worse? Fuhgedaboudit. ****************************** We’ve come to the end of my memoir. What started as a few stories written down for my children has turned into over 70,000 words. Still, with the publication of almost every episode, I get a message from some old friend asking why I hadn’t included such and such story. Well, some I simply chose not to tell; they didn’t fit a certain theme or chapter. Others, like the time I drove a carload of track team friends on a boyish prank that ended with us stopped by the SWAT team, I must have worked hard to erase from my memory. So, in true Canarsie fashion, I’ll make you a deal. I’ll add to the memoir at least once a month with more tales from my old Canarsie experience. It’ll be a good way to keep you interested in my next writing project: a crime novel set in 1904 Brooklyn and Manhattan, with scenes in Canarsie. I’d like you to do something too. Please share your stories with me. I’ll add them to the blog, giving you full credit, of course; or, if you wish, keep them just between you and me. I want to let the world know what a great place Canarsie was, and often still is. Just contact me through this blog, or via email ([email protected]) or through Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. Send me your “Tales of a Canarsie Kid.” So, this isn’t good-bye. It’s just, see ya’ later. To hear this episode, please click the YouTube link below. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed